Sensitive diet products—gluten-free, allergen-free and intolerance-friendly—are big, big business today. They’ll be Bill Gates big by 2017, when the global market is predicted to crest $26 billion (1). It’s a classic case of supply meeting demand. The result for those with special dietary restrictions is increased selection and a more fulfilling experience with their food. The implication for product makers certainly involves more profit, but there’s also an imperative to continue to satisfy, reach out to and protect their new customers.

You Better Shape Up

Gluten-free shoppers of decades past should be forgiven if they thought these foods would never taste good. Most do today. What’s changed is that an increased awareness and, unfortunately, an apparent increase in food allergies and other sensitivities have created a demand that’s fostered innovation and competition among food alternative manufacturers. “It has allowed companies like us and our competitors to put much more of a focus on R&D,” says Jamie Schapiro, director of marketing for Galaxy Nutritional Foods Company, North Kingstown, RI. Each product maker, he explains, is striving to make its offerings best of class.

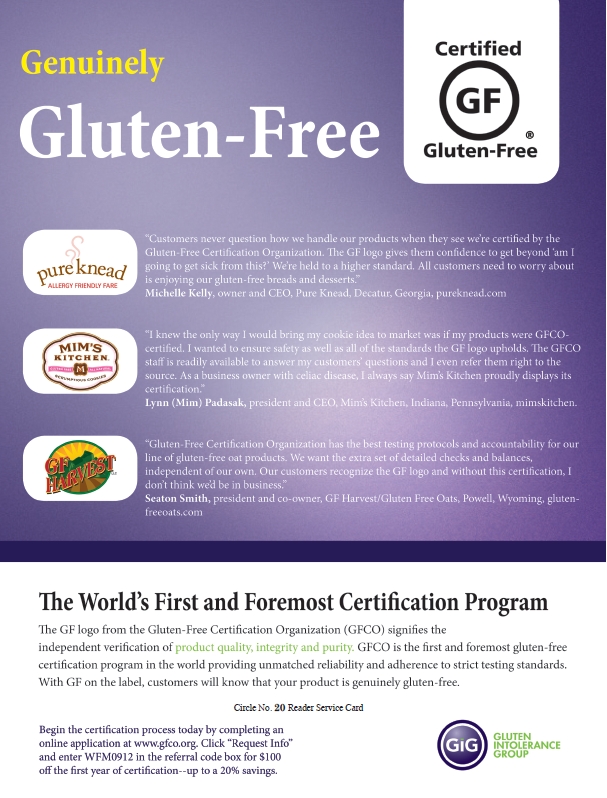

The result is dramatically improved availability,  selection, taste and nutritive value in allergy-, intolerance- and sensitivity-safe products. But not all is perfect yet; there’s still work to do in some areas, according to Cynthia Kupper, R.D., executive director of the Gluten Intolerance Group, operating the Gluten Free Certification Organization, Auburn, WA. “Availability is still a concern—especially in regions where there are not a lot of health stores. Gluten-free products moving into major grocery chains are making an impact, but the variety there is limited,” she says.

selection, taste and nutritive value in allergy-, intolerance- and sensitivity-safe products. But not all is perfect yet; there’s still work to do in some areas, according to Cynthia Kupper, R.D., executive director of the Gluten Intolerance Group, operating the Gluten Free Certification Organization, Auburn, WA. “Availability is still a concern—especially in regions where there are not a lot of health stores. Gluten-free products moving into major grocery chains are making an impact, but the variety there is limited,” she says.

Cost also tends to be a barrier in these product spaces. “Gluten free products continue to have markups that exceed their wheat-based counterparts. This makes it challenging for people to purchase these foods,” Kupper says. Large manufacturers with leverage are beginning to solve this cost problem, she adds, but there is still room for improvement. As with any specialized market, there is always a way to better serve the consumer. For now, it is important for retailers to understand how consumers are affected by the advances that we have seen, and what strides are continuing to be made.

Taste the difference. In improving the taste profiles of products for sensitive diets, and also addressing elements related to the experience of food like texture, mouth-feel, appearance and functionality, manufacturers have improved the quality of life of their customers. For those with lactose intolerance, for instance, rediscovering ice cream or experiencing it for the first time is a true gift. “We hear on a daily basis how much people love the flavor and creaminess of Coconut Bliss, and how happy they are to discover us in their grocer’s freezer case,” says Karen Campbell, quality assurance manager for Coconut Bliss, Eugene, OR.

The significance of taste breakthroughs in these categories goes beyond individual satisfaction. “As a manufacturer who also is a clinical psychologist and the mother of a child with food allergies, the shift toward taste is very welcome. That is because a shift toward taste is correspondingly a shift toward inclusion: If it tastes good, everyone will eat it together,” says Jill Robbins, founder and president of HomeFree, Windham, NH. One of her goals in founding her company was to offer cookies that taste good enough for a child with gluten intolerance or Celiac disease to be able to share them with family or their classmates.

The significance of taste breakthroughs in these categories goes beyond individual satisfaction. “As a manufacturer who also is a clinical psychologist and the mother of a child with food allergies, the shift toward taste is very welcome. That is because a shift toward taste is correspondingly a shift toward inclusion: If it tastes good, everyone will eat it together,” says Jill Robbins, founder and president of HomeFree, Windham, NH. One of her goals in founding her company was to offer cookies that taste good enough for a child with gluten intolerance or Celiac disease to be able to share them with family or their classmates.

The shared experience of eating, along with easing the burden on the person in a family who shops, really shouldn’t be neglected as an aspect of catering to this clientele. For Jennifer Lynn Bice, owner/CEO of Redwood Hill Farm & Creamery and Green Valley Organics, Sebastopol, CA, her company’s lactose-free, real dairy products must be delicious to be successful. “This way the whole family can enjoy the same products and not have to buy different items for different members of the family,” she says.

In developing his company’s vegan seafood substitutes, Eugene Wang, founder of Sophie’s Kitchen, Sebastopol, CA, had a person close to him in mind. His daughter Sophie is affected by seafood sensitivity, and he initially conceived of the idea so she would have something to eat when others were eating seafood. He especially wanted to make sure it appealed to her young taste buds. “In our business, there’s a saying that if you can get kids to eat your product, that means your product is really good,” he says, adding that if kids like it, many adults are sure to as well.

The central ingredient in this line of seafood  substitutes is seldom found in American food products as of yet. The texture of konjac, a plant used as food for centuries in many Asian countries, has been long-regarded as similar to some seafoods. Wang says that some Japanese manufacturers have tried to mimic shellfish or squid, without necessarily getting the consistency right, and often including unnatural additives. With years of experience in manufacturing vegetarian products behind him and his formulation team, Wang took note that the texture of konjac was similar to shrimp, which Sophie enjoyed. The end result is a product that those with seafood allergies and vegans can look to for a similar palate experience to eating a variety of seafood.

substitutes is seldom found in American food products as of yet. The texture of konjac, a plant used as food for centuries in many Asian countries, has been long-regarded as similar to some seafoods. Wang says that some Japanese manufacturers have tried to mimic shellfish or squid, without necessarily getting the consistency right, and often including unnatural additives. With years of experience in manufacturing vegetarian products behind him and his formulation team, Wang took note that the texture of konjac was similar to shrimp, which Sophie enjoyed. The end result is a product that those with seafood allergies and vegans can look to for a similar palate experience to eating a variety of seafood.

Schapiro says that there are two kinds of shoppers in the dairy-substitute market. Some have had their allergy their whole life, and don’t really know what their offending food tastes like. Then there are those who developed an allergy or intolerance later, or have voluntarily chosen to follow a special diet like veganism. Meeting the expectations of those individuals looking for a cheese substitute, he says, is what provides his company with a challenge. He feels his company has made progress with products like vegan cream cheese and cheese shreds. By culturing the cream cheese overnight like regular cream cheese, for instance, a mouth-feel, “spreadability” and taste are achieved that are similar to the standard people are used to.

Other issues manufacturers face involve the removal of crucial ingredients to fit sensitive diets. For his company’s casein-free cheese product (they also have a product that does contain it), Schapiro explains the innovation required. “Casein is a milk protein, and ultimately when you take casein out of a product and you want to make it vegan, it’s really difficult to make that product melt, stretch and taste good,” he says. Casein serves in part as an emulsifier, important to how cheese behaves under different conditions.

Ingredients like soy, rice and corn starch have been used in such cheese substitutes to help recreate important qualities of cheese. It took the right blend of gums, proteins, solids and fats, according to Schapiro, to give their product desirable cheese-like qualities from mouth-feel to melting. He notes that these ingredients must work as emulsifiers and stabilizers to achieve the desired results. “There’s a complete science behind this, and it’s taken us a very long time to figure it out, but we do feel like we’ve cracked it,” he says.

Ingredients like soy, rice and corn starch have been used in such cheese substitutes to help recreate important qualities of cheese. It took the right blend of gums, proteins, solids and fats, according to Schapiro, to give their product desirable cheese-like qualities from mouth-feel to melting. He notes that these ingredients must work as emulsifiers and stabilizers to achieve the desired results. “There’s a complete science behind this, and it’s taken us a very long time to figure it out, but we do feel like we’ve cracked it,” he says.

Rebalancing the diet. The nutritional needs of sensitive-diet shoppers do not differ from others, except regarding what they cannot eat. So, when excluding certain foods from the diet results in nutritional deficiencies or imbalances for these individuals, manufacturers must step up to the dinner plate with answers. Ideally, sensitive-diet alternatives should also be healthy dietary choices in a general sense. Often, the processes and choices available for developing food alternatives result in a lighter, more nutritious product.

Campbell says that her company’s ice cream alternative was not only designed to be dairy-free and free of refined sugar. It was also meant to be a dessert with healthful attributes. “Coconut milk and agave syrup were chosen as the base ingredients specifically for their nutritive qualities. Coconut milk is being discovered as a health food all its own, due in large part to the healing properties of coconut fat called MCTs (medium-chain triglycerides), and it is cholesterol-free,” she says. Naturally low-glycemic, agave syrup for use as a sweetener is created through a heating and filtering process. Campbell says her company focuses on minimally processed, healthy ingredients, and on steering clear of the additives that can sometimes find their way into replacement foods.

For manufacturers tasked with replacing a primary ingredient  with significant nutrient density, there are inevitably some limitations. “When creating an alternative product, we seek to understand what additional nutrition we can offer,” says Tina Nelson, vice president sales and marketing, consumer products, SunOpta Grains & Foods Inc., Edina, MN. She uses her company’s SoL Sunflower Beverage as an example, because as a non-dairy beverage that is also free of eight common allergens, it was going to be tough to replace the protein provided by dairy or soy. But, there is a positive tradeoff: “We could, however, offer a beverage that offers the nutrition of a nutritionally dense sunflower seed,” she says. This translates into a product fortified with calcium, vitamins A and D in levels comparable to dairy, 50% of the RDA of vitamin E, 20% RDA of folic acid, and electrolytes that aren’t even present in most dairy or soymilks.

with significant nutrient density, there are inevitably some limitations. “When creating an alternative product, we seek to understand what additional nutrition we can offer,” says Tina Nelson, vice president sales and marketing, consumer products, SunOpta Grains & Foods Inc., Edina, MN. She uses her company’s SoL Sunflower Beverage as an example, because as a non-dairy beverage that is also free of eight common allergens, it was going to be tough to replace the protein provided by dairy or soy. But, there is a positive tradeoff: “We could, however, offer a beverage that offers the nutrition of a nutritionally dense sunflower seed,” she says. This translates into a product fortified with calcium, vitamins A and D in levels comparable to dairy, 50% of the RDA of vitamin E, 20% RDA of folic acid, and electrolytes that aren’t even present in most dairy or soymilks.

With other food alternatives, different solutions are available. “People get calcium from milk, so when they’re having a cheese alternative, there’s no dairy in it. People want to make sure they still have the right calcium levels for their bones and their health,” says Schapiro. His company’s product is therefore fortified with calcium, in amounts comparable to the calcium content in real cheese. They also include pea protein to make up for the lack of casein.

With konjac, the ingredient found to be suitable for vegan seafood, consumers get a high-fiber, low-calorie ingredient that is plant-based, meaning no cholesterol and lower fat in contrast to real seafood. Wang also tasked his formulation team to develop these seafood substitutes with natural ingredients, meaning no preservatives, artificial coloring or flavoring. Anecdotally, Wang says he was told by a friend that “over 50% of the diet products in Japan are actually made out of konjac,” a prevalence which he believes contributes to Japan’s status as one of the healthiest developed nations.

Few gluten-free products are enriched, according to Kupper, and so with the removal of gluten and other factors, this diet may leave something to be desired nutritionally. “Since living gluten-free means avoiding major sources of B-vitamins, we are concerned about a balanced diet. The typical gluten-free diet is lacking in many nutrients. Either consumers need to be educated in making gluten-free selections that will add these nutrients back to the diet, or use gluten-free vitamin and mineral supplements,” she says.

Few gluten-free products are enriched, according to Kupper, and so with the removal of gluten and other factors, this diet may leave something to be desired nutritionally. “Since living gluten-free means avoiding major sources of B-vitamins, we are concerned about a balanced diet. The typical gluten-free diet is lacking in many nutrients. Either consumers need to be educated in making gluten-free selections that will add these nutrients back to the diet, or use gluten-free vitamin and mineral supplements,” she says.

“The primary nutrient often missing in gluten-free baked goods is whole grain, because these products to date usually are made with starches and white rice flour,” notes Robbins. She says that this is why her company placed an emphasis on including gluten-free whole grains in its cookies, to the point of being certified as a good source of this heart-healthy ingredient. This is done, she adds, without affecting texture so that children will still enjoy them.

With innovations like lactose- but not dairy-free products, individuals who are only lactose intolerant don’t need to miss a nutritional beat. “Those with lactose intolerance were avoiding real dairy and by doing so, missing out on important nutrients like calcium and protein. Now, customers can enjoy real dairy without the problems,” says Bice of her company’s offerings.

Sensitive-diet shoppers don’t necessarily need to miss out on the health benefits of many mainstream products, as long as they know what’s safe for them. Those with lactose-intolerance can join in on a trend like kefir, for instance. Fallon Fleyshman Morgan, operations director at Lifeway Foods, Morton Grove, IL, says her company has focused on touting that kefir is naturally 99% lactose free on the product label. “More consumers are complaining of lactose intolerance issues. The probiotics in our kefir eat away the lactose,” she says.

Make Their Lives Easier

With their products at your store and on the shelf, the manufacturers have done their job. There is still yet another piece of the puzzle needed to fully accommodate the sensitive-diet shopper, and that comes when the retailer decides how to position, promote and educate about these products. Such decisions must complement the ones that manufacturers have already made on their packaging, in order to make shopping efficient for these individuals and their caretakers.

Opinions vary on the manufacturer side, but all want what’s in the best interest of customers. “We feel that keeping all items together within their normal category sets, while providing clear shelf tags stating whether a product is gluten-free, dairy-free, non-GMO, etc. is the best scenario,” says Marc Donofrio, national sales director for Coconut Bliss. If a separate “allergen free” section is established, those products should also retain space within the regular set, he believes. His reasoning is that not everyone that picks up a sensitive-diet product has that specific diet issue, and no product should be pigeon-holed as exclusively for those with sensitive diets.

Kupper agrees that the decision is difficult, especially in the gluten-free space. “Gluten-free shoppers spend more time shopping than most consumers because they are label readers. Many consumers report that they prefer special sections where they can find the specialty products rather than having to hunt for them throughout a store.” Kupper also suggests the use of shelf talkers positioned to help consumers rapidly find gluten- and allergen-free products wherever they are positioned next to their standard counterparts.

Kupper agrees that the decision is difficult, especially in the gluten-free space. “Gluten-free shoppers spend more time shopping than most consumers because they are label readers. Many consumers report that they prefer special sections where they can find the specialty products rather than having to hunt for them throughout a store.” Kupper also suggests the use of shelf talkers positioned to help consumers rapidly find gluten- and allergen-free products wherever they are positioned next to their standard counterparts.

“There are certainly advantages to a [sensitive diets] set, including ease of shopping, as well as comfort that desired foods are not placed next to concerning foods,” Robbins explains. Inclusiveness is a welcome gesture when moving in this direction. “Stores can help by extending their ‘gluten free’ sets to being ‘sensitive diet’ sets, ideally with a sub-section for ‘allergy friendly’ or ‘peanut/nut free,’” she says. Alternately, retailers can use “peanut free” or “nut free” shelf tags to identify individual products made in peanut or nut free facilities. This can work across the board, as Bice relates that when they introduced the concept of lactose-free yogurt, sour cream and other items, they created shelf danglers so that retailers could thus steer their lactose-intolerant shoppers to this new option.

Wang’s experience with his company’s products is that they are only placed in the meat alternative freezer. But he has concerns about ocean pollution, and is of the belief that some seafood sensitivity in the general population could be due to the quality of the fish we’re now eating, noting that he personally reacts differently to eating fish in different parts of the world.

He thinks seafood alternatives may become a more popular concept, saying, “As time goes on, I believe our product is going to be accepted by a lot of people, it’s going to be everywhere. When that time comes, I believe we’re going to be put next to the seafood section so that people will have an option.” By the end of the year, Wang’s company will introduce non-frozen products like vegan canned tuna, and they will look for them to be cross-merchandized in special diet sections and alongside real seafood.

Schapiro observes that “in general, most of  the cheese alternatives are positioned right next to the cheese.” Other than their being placed together, he doesn’t believe many retailers make a point of highlighting or calling out this special set of products in the freezer case. He places some of the responsibility for calling attention to these products with the retailer, but thinks that the manufacturer’s decisions are an important factor. Says Schapiro, “If the manufacturer is doing the right job in building transparency on their packaging, it makes it easier for the consumer.” People with special diets are already label readers, so manufacturers must clearly promote the exclusion or inclusion of certain ingredients.

the cheese alternatives are positioned right next to the cheese.” Other than their being placed together, he doesn’t believe many retailers make a point of highlighting or calling out this special set of products in the freezer case. He places some of the responsibility for calling attention to these products with the retailer, but thinks that the manufacturer’s decisions are an important factor. Says Schapiro, “If the manufacturer is doing the right job in building transparency on their packaging, it makes it easier for the consumer.” People with special diets are already label readers, so manufacturers must clearly promote the exclusion or inclusion of certain ingredients.

Companies are making the effort to improve in this area. “We sat down with consumers, and went through a major Attitude and Usage study with people that use cheese alternatives,” says Schapiro. They learned that obvious, well-placed indications denoting allergen-free, and in their case casein-free products, are important to these shoppers.

To hold up their end of the bargain, he thinks retailers must consider how they highlight products, even in areas with limited space like the dairy freezer. In dealing with individuals for whom going to a restaurant and ordering a meal can be an ordeal, it helps to make things efficient. “They want to have an easy shopping experience, because their lives aren’t easy,” Schapiro says.

Robbins says that many of her company’s customers must travel from store to store, and sometimes are even forced to search online to find enough items that are both safe and tasty. “This is because it typically is hard to find them all in one location. Stores that service this growing population by having a broad allergy friendly set will gain a great deal of appreciation and store loyalty,” she says.

Robbins says that many of her company’s customers must travel from store to store, and sometimes are even forced to search online to find enough items that are both safe and tasty. “This is because it typically is hard to find them all in one location. Stores that service this growing population by having a broad allergy friendly set will gain a great deal of appreciation and store loyalty,” she says.

Last, but not least, education and community engagement are especially important with this set of customers. Nelson states, “For newly diagnosed customers, it’s important to provide some in-store expertise on allergens if at all possible. This could be in the form of a staff member that has training or specific knowledge about allergens or via publications and newsletters that are widely available.”

Protecting the Vulnerable

Food safety takes on a special importance in the context of food allergies and intolerances. No one wants a product recall of course, but in a market where companies often have a personal connection with their customers, the thought of harm coming to any of them is impetus enough to get safety right the first time. “Lab testing for residual proteins is nearly constant,” says Campbell of the dairy-free ice cream business. “The risk of making a customer ill, and all that is lost in a recall, are powerful motivators for food producers to always work within the lines of allergen control.”

Well-defined standards, if not regulations, for manufacturing, currently give  companies guidelines on how to operate safely. “Allergens are always a concern at the manufacturing level and each company should already have their Good Manufacturing Practices in place to address handling and processing allergens,” says Nelson. Schapiro notes that his company tests for allergens prior to, during and post-production. He also adds that retailers, especially massive ones like Whole Foods Market, are acting as effective gatekeepers on issues like gluten- and allergen-free foods, consistently requiring extensive documentation of safety procedures.

companies guidelines on how to operate safely. “Allergens are always a concern at the manufacturing level and each company should already have their Good Manufacturing Practices in place to address handling and processing allergens,” says Nelson. Schapiro notes that his company tests for allergens prior to, during and post-production. He also adds that retailers, especially massive ones like Whole Foods Market, are acting as effective gatekeepers on issues like gluten- and allergen-free foods, consistently requiring extensive documentation of safety procedures.

There are no specific federal regulations on gluten-free yet, Schapiro notes. There are various certifying agencies available, but it remains to be seen how effective this is at maintaining safety, and how much confidence it inspires in consumers. Nelson calls the gluten-free explosion a challenge, in part because manufacturers are finding themselves labeling products as gluten-free that would never ordinarily contain gluten. Fleyshman Morgan says of her company’s motivations, “We are naturally gluten free, but went through the gluten certification audit to gain consumers’ trust as they’re learning about items that they can and cannot eat. This helps back up our messaging on the packaging.” Nelson thinks that clearer messaging in the marketplace might be welcomed by consumers.

“The FDA needs to complete a ruling on gluten-free labeling. This was a mandate of Congress that was to be completed in 2008. I hope that we will see the finished ruling by the end of 2012,” says Kupper. Once this ruling is made, she anticipates other food and beverage regulatory agencies, like the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Tax and Trade Bureau, will adopt and begin enforcing the rulings. Aligning the efforts of these agencies, she says, will greatly aid manufacturers and improve consumer confidence in the regulations.

Meanwhile, third-party allergen-free certifications can benefit the market, Robbins says. She notes that research shows clinically significant amounts of cross-contamination does occur between shared facilities with peanuts, and allergic reactions in this area can be life-threatening. “Yet, due to limited regulation, a product can be labeled ‘peanut free’ from shared facilities and even shared lines. This makes shopping challenging for the consumer, and makes attribute labeling complicated for stores,” she says.  Certification helps consumers to easily identify high standards, according to Robbins, while streamlining the process for retailers as they determine how to stock their allergy friendly sets.

Certification helps consumers to easily identify high standards, according to Robbins, while streamlining the process for retailers as they determine how to stock their allergy friendly sets.

Wang explains that his company follows regulations for tree nuts, wheat, soy and dairy allergies, and calls this out on packaging. They’ve moved in the direction of catering to allergy-free shoppers of all stripes, as the company seeks to phase out gluten from all of its products soon on top of being a mostly soy-free line, except for retaining one soy product for those who value the ingredient.

He echoes the notion that retailers are taking the bull by the horns with safety checks on manufacturers, and suggests this will eventually lead to bigger changes. “I think it’s just a matter of time that this will get to the government. If the retailers notice it, that means the consumers are making enough requests to get retailers to act,” Wang says. Such oversight may initially be a hassle for vendors. “But, to add it all up, it’s a very good thing for the whole world,” he says, because it’s not only good for consumers, but weeds out the bad vendors from the good.

thing for the whole world,” he says, because it’s not only good for consumers, but weeds out the bad vendors from the good.

Going hand in hand with customer safety and education from the retailer’s perspective is the prospect of getting further engaged. Nelson encourages retailers to become well-versed in the range of allergy groups that these customers may already be involved with or could reach out to. She says the most comprehensive group may be the Food Allergy & Anaphylaxis Network (FAAN), as it covers all allergen concerns and offer recipes along with a variety of other resources.

“I think that it’s important for retailers to understand how the manufacturers are getting involved in the community and aligning themselves with organizations,” Schapiro says. He cites FAAN as a venue where his company connects with customers. Retailers can and do hop on board, too, by participating in allergy community walks and educational events to show their community they care. Partnerships between manufacturers and retailers can be formed through events like this as well. WF

Reference

1. “Global Food Allergy and Intolerance Products Market to Surpass $26 Billion by 2017, According to a New Report by Global Industry Analysts, Inc.,” http://www.prweb.com/releases/2011/4/prweb8310957.htm, accessed on Aug. 1, 2012

Published in WholeFoods Magazine, September 2012