Most Americans, if they know about yeasts at all, are only familiar with baker’s and/or brewer’s yeasts, that is, the yeasts used to make bread and to produce beer and wine. In the natural health world, the term “yeast” is typically associated in a positive way with these “brewer’s/nutritional” yeasts and in a negative way with Candida albicans (as in “yeast infection” and “yeast overgrowth”). One association that is not commonly made is “probiotic.”

Nevertheless, that’s exactly what Saccharomyces boulardii is: a beneficial yeast used as a probiotic agent to support gastrointestinal health. S. boulardii is a “friendly” yeast. Its most important general employment is its response to intestinal flora coming under assault, such as during antibiotic treatment or travel. It also has a record of being helpful to those with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Medically, S. boulardii has several specialty uses, most particularly as an aspect of Clostridium difficile management. C. difficile can multiply in response to antibiotic treatment. Ironically, one successful intervention is another round of the appropriate antibiotic treatment combined with S. boulardii supplementation. S. boulardii, which is resistant to gastric acid and not normally affected by antibiotics, typically reaches a maximum steady state in three days when taken orally and is cleared after discontinuation within two to five days (1–2). In other words, it does not seem to multiply in the gut. Less than 1% of the ingested dose is recovered from stools, indicating that supplementation with S. boulardii should take place regularly to maintain protection.

S. boulardii is a temporary resident in the intestines that is easily displaced by probiotic bacteria. Indeed, it can be used to help restore and promote normal microflora. S. Boulardii can be taken beneficially in combination with lactic-acid producing probiotics (e.g., lactobacilli, bifidobacteria).

Discovery

The story of S. boulardii goes back to the early twentieth century. In the 1920s, the French had a significant presence in Indochina. Many foodstuffs found in the relatively cool climate of Western Europe could not be produced in the much warmer temperatures found in Southeast Asia. Among these was wine. The yeasts used to ferment grapes in France did not make good wine in Indochina. A French microbiologist named Henri Boulard was seeking a new strain of yeast that would withstand extreme heat when he stumbled across yeast with unexpected protective properties. Today, we can safely perform research in animals to examine diseases and responses to toxins in humans, hence research titles such as “Protective Effect of S. boulardii against the Cholera Toxin in Rats” (3). However, Boulard faced the real disease during his travels in Indochina and observed that the locals could stop the associated diarrhea by drinking a tea made from the skins from the tropical fruit lychee (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) and mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana). Boulard managed to isolate the active agent as a special strain of yeast of the Saccharomyces genus, which he named after himself “S. boulardii.”

After its discovery by Boulard, S. boulardii initially was developed in Europe to improve gastrointestinal resistance to assault by pathogenic organisms. Indeed, it is one of the most thoroughly researched of all probiotic products available as supplements. A 2010 review noted that there are currently “53 randomized controlled clinical trials, encompassing 8,475 subjects, investigating the safety and efficacy of S. boulardii in pediatric and adult patients spanning several disease indications, of which 43 (81%) found significant efficacy for S. boulardii….There have been 27 randomized controlled trials, with 31 treatment arms testing S. boulardii in adult patients for a variety of diseases and most (84%) found a significantly protective efficacy of this probiotic” (4). Including non-clinical trials, there have been hundreds of peer-reviewed studies.

Multiple Mechanisms of Protection

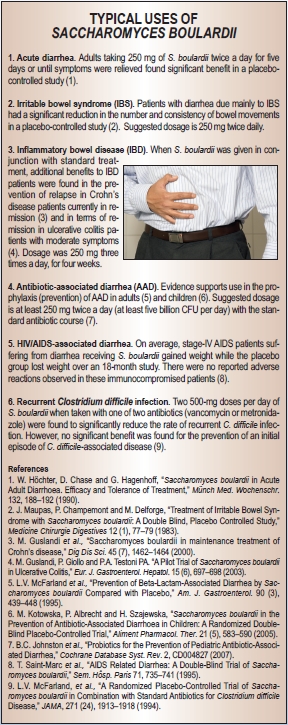

S. boulardii is recommended for a range of conditions. Aside from recurrent C. difficile infections, the most prominent are various other types of diarrhea including acute diarrhea, antibiotic-associated diarrhea, some parasitic forms of diarrhea (co-treatment with antibiotics) and more. Irritable bowel syndrome, Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis round out the usual uses. It is unlikely that only one mechanism of action would prove successful in all these conditions.

In fact, researchers have pursued several leads involving the gut lumen (i.e., the area lying behind the surface of the intestinal lining of epithelial cells), antimicrobial activity, altered enzymatic activity and anti-inflammatory effects. “Within the intestinal lumen, S. boulardii may interfere with pathogenic toxins, preserve cellular physiology, interfere with pathogen attachment, interact with normal microbiota or assist in reestablishing short-chain fatty acid levels. S. boulardii also may act as an immune regulator, both within the lumen and systemically,” according to a recent meta-analysis (4).

Anti-toxin effects. Significant work has been done on the anti-toxin effect of this yeast because of its early use against cholera and its still primary usage against C. difficile and other enteric pathogens. S. boulardii both neutralizes toxins produced by several pathogens and alters the cell signaling of the host to reduce the proinflammatory response induced by these pathogens (5). The former action has been demonstrated many times. In the case of C. difficile, a protein named Toxin A is secreted by the pathogen and causes a great increase in gut wall permeability along with the secretion of fluids. S. boulardii releases compounds that break down both Toxin A and the receptor it activates in the gut wall (6–7). Related compounds from the yeast destroy Toxin B and toxins produced by E. coli and cholera.

Anti-inflammatory effects. S. boulardii exerts anti-inflammatory effects that are important not only in C. difficile, but also in gut inflammation in general and in irritable bowel disease (8–9). Again, the range of actions is broad and includes the inhibition of the global mediator of inflammation nuclear factor-kappa beta and synthesis of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a), the activation of the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-γ) and even the alteration of the movement of T-cells in relevant lymph nodes (10). These anti-inflammatory actions often are grouped under the heading of “cell signaling” and are partially responsible for the protective actions of S. boulardii against many other pathogens, such as E. coli.

Antimicrobial activity and cross-talk with normal microbiota. A large body of evidence documents that S. boulardii directly interferes with the growth of many intestinal pathogens (4). In other cases, it prevents changes in gut wall integrity promoted by pathogens and can act as a “decoy” to which pathogens are attracted and to which these pathogens attach themselves in place of the intestinal wall enterocytes. Such actions arise more or less directly from the nature of S. boulardii acting on its own. In some ways, even more interesting is the finding that this probiotic yeast helps the established gut microbiota maintain barrier function against pathogenic invasion and re-establish barrier function when this is disrupted. This action often is treated under the mechanism of action heading of “trophic effects on enterocytes.” Shocks to normal microflora resist pathogenic invasion and colonization through a variety of mechanisms. Disruption of normal microflora by surgery, antibiotics and other factors can open a window of opportunity for pathogens lasting six to eight weeks (11). Surrogates for normal microflora, such as S. boulardii and other probitiocs, can reduce host susceptibility during this period and help the body more rapidly re-establish normal microflora (12).

Efficacy

Clinically, the effects of S. boulardii can be divided between acute and chronic conditions (4, 13). Among the former are included antibiotic-associated diarrhea, C. difficile infections, Helicobacter pylori infections, acute diarrhea, diarrhea associated with HIV and traveler’s diarrhea. S. boulardii may exhibit some degree of benefit in many or even most of these, yet it should not be mistaken as being universally effective. Most reviews give this probiotic yeast marks for excellent effectiveness against antibiotic-associated diarrhea—meta-analyses of the pooled results from studies suggest that S. boulardii can decrease the relative risk of antibiotic-associated diarrhea by 57–63%. It has good effectiveness against diarrhea in children, and adequate effectiveness against amebiasis and C. difficile when used in conjunction with appropriate antibiotic treatment. For traveler’s diarrhea, it is generally agreed that S. boulardii, as is true of other probiotics, is more successful at preventing or reducing this condition if used before exposure than in treating it once it has manifested.

S. boulardii has been found to be broadly useful in clinical efficacy in chronic conditions. Trials indicate promise and significantly better outcomes with inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease with long-term (six months) co-treatment with S. boulardii. The same is true in the case of irritable bowel syndrome; again, significantly better results were obtained with supplementation than with control. However, the rate of success and degree of improvement in most of these conditions often is only moderate. For instance, the overall improvement in IBS quality of life was higher in the S. boulardii group than in the placebo group (15.4% versus 7.0%; P<0.05) (14). One form of chronic diarrhea, giardiasis, appears to be especially well suited to S. boulardii supplementation. In one clinical trial, S. boulardii not only led to a complete cure rate, but also to 0% remaining giardia cysts compared with standard treatment.

S. boulardii also may benefit skin health. In a randomized, controlled double-blind study involving 139 patients with acne, the effectiveness and tolerance of this probiotic yeast was studied in comparison with a placebo over a maximum period of five months. The results of therapy were assessed as very good/good in 74.3% of the patients receiving the preparation as compared with 21.7% in the placebo group. More than 80% of the people in the S. boulardii group were judged to be considerably or completely improved, while the corresponding figure for the placebo group was only 26%.

As pointed out in the Natural Standard Monograph, S. boulardii is approved in the German Commission E for symptomatic treatment of acute diarrhea, prophylactic and symptomatic treatment of diarrhea during travel, treatment of diarrhea occurring while tube feeding and employment as an adjuvant for chronic acne, among other uses. Moreover, in France 62% of physicians surveyed indicated prescribing S. boulardii for certain types of diarrhea, a rate equal to that for Lactobacillus acidophilus (15).

Safety and Usage

S. boulardii has been used as a probiotic in Europe for more than 60 years and has been the subject of numerous clinical trials. The safety record is excellent. Extremely rare cases of overgrowth have been reported, but only in patients with serious comorbidities and/or central venous catheters; in all such cases, caution is advised. There are few interactions other than with antifungals. However, S. boulardii taken in combination with MAO inhibitors may drop blood pressure. When used in otherwise healthy adults, few if any side effects have been noted in those taking approximately 500 mg to two grams per day for up to 15 months. No standard has been universally agreed upon as to the translation of dosages by weight to colony forming units (CFU) and preparations vary by manufacturer. Inasmuch as this yeast does not multiply in the gut and results are concentration-dependent, a reasonable starting level is five billion CFU taken twice daily or 250–500 mg taken twice daily. WF

References

1. C. Pennacchia et al., “Isolation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains from Different Food Matrices and their Preliminary Selection for a Potential Use as Probiotics,” J. Appl. Microbiol. 105 (6): 1919–1928 (2008).

2. Y. Vandenplas et al., “Saccharomyces boulardii in Childhood,” Eur. J. Pediatr. 168 (3), 253–265 (2009).

3. R.S. Dias et al., “Protective Effect of Saccharomyces boulardii against the Cholera Toxin in Rats,” Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 28 (3), 323-325 (1995).

4. L.V. McFarland, “Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Saccharomyces boulardii in Adult Patients,” World J. Gastroenterol. 16 (18), 2202–2222 (2010).

5. D. Czerucka, T. Piche and P. Rampal, “Review Article: Yeast as Probiotics: Saccharomyces boulardii,” Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 26 (6), 767–778 (2007).

6. C. Pothoulakis et al., “Saccharomyces boulardii Inhibits Clostridium difficile Toxin A Binding and Enterotoxicity in Rat Ileum,” Gastroenterol. 104 (4), 1108–1115 (1993).

7. I. Castagliuolo et al., “Saccharomyces boulardii Protease Inhibits Clostridium difficile Toxin A Effects in the Rat Ileum,” Infect. Immun. 64 (12), 5225–5232 (1996).

8. X. Chen et al., “Saccharomyces boulardii Inhibits ERK1 ⁄ 2 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Activation both in vitro and in vivo, and Protects against Clostridium difficile Toxin-A Induced Enteritis,” JBC; 281 (34), 24449–24454 (2006).

9. C. Pothoulakis, “Review Article: Anti-Inflammatory Mechanisms of Action of Saccharomyces boulardii,” Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 30 (8), 826–833 (2009).

10. G. Dalmasso et al., “Saccharomyces boulardii Inhibits Inflammatory Bowel Disease by Trapping T-Cells in Mesenteric Lymph Nodes,” Gastroenterol. 131 (6), 1812–1825 (2006).

11. L. Dethlefsen, et al., “The Pervasive Effects of an Antibiotic on the Human Gut Microbiota, as Revealed by Deep 16S rRNA Sequencing,” PLoS Biol. 6 (11), e280 (2008).

12. M.C. Barc et al., “Molecular Analysis of the Digestive Microbiota in a Gnotobiotic Mouse Model During Antibiotic Treatment: Influence of Saccharomyces boulardii,” Anaerobe 14 (4), 229–233 (2008).

13. “Saccharomyces boulardii,” Natural Standard Monograph, www.naturalstandard.com, 2009.

14. C.H. Choi et al., “A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-Controlled Multicenter Trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Effect on Quality of Life,” J. Clin. Gastroenterol. Feb. 4, 2011, Epub ahead of print.

15. S. Uhlen, F. Toursel and F. Gottrand, “Association Française de Pédiatrie Ambulatoire. [Treatment of Acute Diarrhea: Prescription Patterns by Private Practice Pediatricians],” Arch. Pediatr. 11 (8), 903–907 (2004),

Published in WholeFoods Magazine, July 2011