On July 23rd, the House of Representatives voted to pass the Safe and Accurate Food Labeling Act of 2015 (H.R. 1599), advancing it along to the Senate with lightning speed.

The bill is now in the hands of the Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry. Should it be passed into law, companies will be allowed to voluntarily use labeling on their products to indicate the presence of genetically modified ingredients, superseding state legislation requiring mandatory labeling like that which will soon take effect in Vermont. With strong opinions coming from both sides of the fence, the Safe and Accurate Food Labeling Act of 2015 has been called one of the industry’s most pivotal issues right now—and while that may be the case, it is also one part of the greater non-GMO debate, which has begun to spill outside the industry as more and more consumers are educating themselves and taking stances.

Leading into Legislation

With the Safe and Accurate Food Labeling Act progressing through Congress, it is important for retailers to take note of exactly what it currently entails and what this means for the marketplace should it become law.

Tami Wahl, special regulatory counsel at the American Herbal Products Association (AHPA), Silver Spring, MD, takes a perspective that may surprise detractors of the Act: “The Safe and Accurate Food Labeling Act has been improved since it was first introduced. The bill now more closely tracks the Organic Foods Production Act, which is what AHPA has been advocating the past two years.” Among the improvements she mentions is that products that are certified organic will also automatically be certified non-GMO as well, which she says “removes potentially duplicative and expensive measures.”

Tami Wahl, special regulatory counsel at the American Herbal Products Association (AHPA), Silver Spring, MD, takes a perspective that may surprise detractors of the Act: “The Safe and Accurate Food Labeling Act has been improved since it was first introduced. The bill now more closely tracks the Organic Foods Production Act, which is what AHPA has been advocating the past two years.” Among the improvements she mentions is that products that are certified organic will also automatically be certified non-GMO as well, which she says “removes potentially duplicative and expensive measures.”

With this said, she does see other issues with the Act as it currently stands, namely that it needs a better definition of a GMO threshold. As she explains it, the current bill would allow products to be labeled GMO free if there is an “inadvertent presence” of GMOs, but this term is not defined.

Courtney Pineau, associate director of the Non-GMO Project, Bellingham, WA, shares some concerns with H.R. 1599. She notes that part of the revised bill includes a mandate for the USDA to begin creation of its own non-GMO certification program, something that she believes “would operate to drastically lower standards than those of the Non-GMO Project.”

While she assumes that the presence of a non-GMO certification from the USDA would not automatically supplant those offered by the Non-GMO Project, “the bill as written would create a compe ting label that would confuse shoppers and undermine the tremendous progress we’ve made on setting a high standard for GMO avoidance.”

ting label that would confuse shoppers and undermine the tremendous progress we’ve made on setting a high standard for GMO avoidance.”

One issue that many trade groups agree is a problem with the Act is its effect on legislation already on the books. Part of the Act also includes prohibiting any current or future state law on GMO labeling, which Pineau says “would negate more than 130 existing statutes, regulations and ordinances in 43 states at the state and municipal level.”

Daniel Fabricant, Ph.D., CEO and executive director of the Natural Products Association (NPA), Washington, D.C., points out that while the Safe and Accurate Food Labeling Act is what’s on everyone’s mind, other legislation regarding GMO labeling is also a possibility. “Senator Hoeven (R-ND) is believed to currently be working on a similar bill that would include more USDA involvement,” he says, noting that this potential bill would also overwrite any current state-level legislation.

Going to Non-GMO

Outside of the legislative sphere, non-GMO remains the popular buzzword. A recent consumer study from Health Focus International showed that 87% of consumers globally think that non-GMO foods are “somewhat” or “a lot” healthier than their GMO counterparts. Results also showed that 63% believed that GMOs were “less safe to eat” and 55% saw GMO crops as “worse for the environment (1).” With such a strong tide of public support, many food companies are taking notice and making strides toward non-GMO. According to the Non-GMO Project’s website, it currently has over 27,000 Non-GMO Project Verified products from 1,500 brands, representing over $11 billion in annual sales (2).

Many of these companies are from the natural products industry, but consumer interest in non-GMO has resulted in conventional food companies and food service businesses making the move as well. Earlier this year, fast-casual restaurant Chipotle Mexican Grill announced that its over 1,800 locations would be making the move to non-GMO ingredients. As of press time, a class-action lawsuit has been leveled against Chipotle claiming that its meat, sour cream, and cheese come from animals that eat GMO feed, despite this claim of using only non-GMO ingredients. The number of mainstream companies either making the move to non-GMO completely or exploring non-GMO options is rising as well. So, where is this all coming from?

Brandy Gamoning, marketing manager of NestFresh, Denver, CO, doesn’t see the interest in non-GMO as too much of a surprise, “considering today’s consumer is looking for transparency in the food they feed themselves, as they  are entitled to do.” She says that many companies are beginning to see the correlation that “the cleaner the label and the more public the production process, the higher the demand for their product.” She also notes, though, that the relationship between transparency and consumer satisfaction is taking a bit of turn as well, saying “transparency in every step is not a bonus; it is a prerequisite.” Transparency is becoming a consumer expectation as opposed to something that draws praise for going above and beyond.

are entitled to do.” She says that many companies are beginning to see the correlation that “the cleaner the label and the more public the production process, the higher the demand for their product.” She also notes, though, that the relationship between transparency and consumer satisfaction is taking a bit of turn as well, saying “transparency in every step is not a bonus; it is a prerequisite.” Transparency is becoming a consumer expectation as opposed to something that draws praise for going above and beyond.

Trudy Bialic, director of public affairs at PCC Natural Markets, Seattle, WA, uses Chipotle as an example, saying “Chipotle understands that avoiding consumer concerns, such as genetic engineering, eventually hurts a brand. Transparency is a selling point and it’s best to be out in front of the pack.”

Things are beginning to get to the point where visible measures that showcase a company’s dedication to transparency, such as non-GMO verification, are in demand to avoid consumer ire as much as they are to make them happy—note that these two goals are not necessarily one and the same.

While non-GMO demand is already front and center for many, mainstream companies making this move could cause the trend to gain even more steam. Kate Brown, founder and president of Boulder Organics, Longmont, CO, believes, “The larger companies can go a long way in setting the standards that customers come to expect; if they are going to make the effort to use non-GMO products, we hope they get the message out to their customers, loud and clear.”

Some believe that the non-GMO issue is a great way for companies to advance their profile by positioning themselves on an issue while others are more reticent. Michael Potter, president of Eden Foods, Clinton, MI, remarks: “I applaud those pointing out in any way that avoidance of GMOs is wise and valuable for the public. With the corporate media completely ignoring this issue and all facts associated with it, it is critically essential for companies with an understanding of the importance of avoiding GMOs to speak out ‘commercially.’”

Non-GMO vs. Organic

Non-GMO vs. Organic

As mainstream interest in non-GMO grows, so does the amount of consumers seeking education before they take the next step. One such area that could be a cause for confusion is the relationship between non-GMO and organic. Many of these newcomers may not entirely understand the relationship between these two terms, which poses a question to natural products companies: should a company already certified organic take the step to go non-GMO as well?

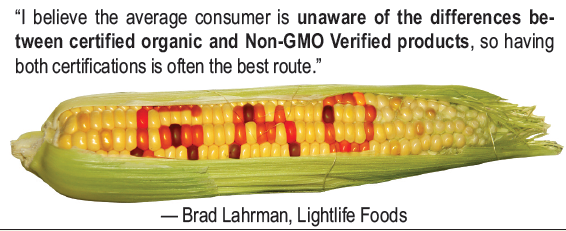

Brad Lahrman, director of marketing at Lightlife Foods, Turners Falls, MA, says that this potential confusion was exactly why his company pursued dual certification. While his company’s tempeh was already certified organic, “I believe the average consumer is unaware of the differences between certified organic and Non-GMO Verified products, so having both certifications is often the best route,” he explains.

Gamoning says that her company sells both options in order to “offer shoppers more freedom in choosing the foods they eat and provide them with the ability to make a more informed decision.”

Even though her organization supports legislation that would allow certified organic foods to be automatically labeled as GMO-free, Wahl is also a proponent of dual certification, both to keep consumers who don’t entirely understand the relationship at ease as well as to respond to the increase in non-GMO demand. Revisiting how transparency has become an expectation for many consumers, dual certification for businesses may serve as a sort of “conscious marketing tool.” It’s an increasingly common occurrence for sustainability and health concerns to merge with consumer demand—and this serves as an example.

However, this doesn’t necessarily mean every company needs to follow this path to communicate transparency to consumers. Joel Warady, chief sales and marketing officer at Enjoy Life Foods, Schiller Park, IL, says that while many ingredients in his company’s products are organic, “with our products being Certified Gluten-Free and free-from the eight most common food allergens (no wheat, dairy, peanuts, tree nuts, soy, egg, fish or shellfish), our products are already at a premium price point.” He also believes that Non-GMO Project certification has more resonance among his company’s consumers than USDA Organic certification. Getting certification can be a long process that incurs cost both in money and energy—so keep the potential benefits and the work it takes to get there in equal consideration.

Keeping It Safe

Keeping It Safe

Earlier, it was mentioned that a consumer survey showed that a sizable amount of consumers believe that GMOs are unsafe. While there is no official answer one way or the other, many deeply rooted opinions on both sides of the debate have developed. In fact, Bialic mentions that “more than 300 molecular biologists, biotechnologists and legal experts have signed a statement that there is ‘no consensus’ on the safety of genetically engineered (GE) crops or foods,” in the Environmental Sciences Europe journal. The main reason for this is a lack of long-term feeding studies in humans. However, Bialic believes that results of studies that have been done, both on humans and animals, “while not conclusive, certainly raise questions and concerns among many scientists, health practitioners and consumers.”

Arjan Stephens, executive vice president of sales and marketing at Nature’s Path, Richmond, British Columbia, Canada, shares the belief that “GMO ingredients have never been adequately tested for long-term impacts on public health, so we cannot say they are safe.” However, he believes that aspects related to GMO crops outside of the genetic engineering itself may be a cause for concern that already has scientific grounding. Glyphosate—known to many as Roundup—is a chemical often sprayed on GM crops. In fact, Pineau says, “more than 80% of all GMOs grown worldwide are engineered for herbicide tolerance and/or to produce an insecticide.” As a result, she says usage of chemicals like glyphosate has increased by over 15 times since the introduction of GMOs. Stephens says that glyphosate has been shown to be harmful in some scientific studies to both consumers and farmers harvesting these crops. He cites a review of 44 studies suggesting that glyphosate exposure played a role in increased levels of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma among farmers (3).

While there is still scientific divide over the question of safety, it is still one part of a larger equation. Fabricant mentions, “these studies do not have any bearing on a consumer’s right to know what is in the product they are purchasing.” His organization also “supports FDA consistently reviewing the concept of bio-equivalency of genetically modified ingredients in light of the most recent scientific studies and methodologies.”

Wahl’s organization is not taking a stance on the safety question, but still is dedicating much time and energy to supporting labeling efforts, with her explaining that “consumers want this information and AHPA strongly believes that consumers have the right to know what is in their food so they can make informed purchasing decisions.” Whichever way the discussion of GMOs and safety goes, many trades and experts support keeping consumers informed every step of the way.

While the scientific community continues to delve deeper, what is the retailer to do? Warady agrees with the train of thought that GMO research is still in its relative infancy, and supports the belief that “until there is that certainty that GMOs are 100% safe or 100% unsafe, we will let the consumer make the decision based on awareness.” At the same time, he asks, “if we can make great-tasting products without having to include GMO ingredients, why wouldn’t we? We like to err on the side of caution.” All of his company’s products are currently Non-GMO Project Verified.

The Other Cost of Non-GMO

While further study will be needed to create a concrete answer on the GMO safety issue, there is another major topic at play here: cost. Many detractors of mandatory GMO labeling point out increased cost as a cause for concern, and some see GMO foods as a way to decrease food cost overall while raising availability. This poses a multi-fold question: does non-GMO equal higher food cost? What of labeling? If it is higher, by how much and who shoulders it?

Stephens believes that any costs associated with mandatory GMO labeling would be minimal, but also that the situation isn’t particularly unique. He says that when it comes to labeling, “the fact is, manufacturers change their packaging all the time…It’s simply the cost of doing business.”

Bialic takes a global perspective, saying “It’s silly to think labeling would increase food costs here when it hasn’t increased food costs in any of 64 other countries with GE labeling in place.” The presence of mandatory labeling abroad is one of the biggest rallying points for supporters of mandatory GMO labeling in the United States. She also mentions that some aspects of the cost argument mirror those leveled at listing food ingredients and nutrition facts in the 1980s. “Once ingredients and nutrition facts were required by the National Education and Labeling Act (1990), only then did they acknowledge cost was not a significant factor,” she says.

Pineau adds that the impact of these changes at the consumer level are minimal, citing information from Consumer Reports that suggests that mandatory GMO labeling “would cost consumers $2.30 per year, less than a penny per day (4).” She says that outside factors such as shopper demographics, brand competition and cost of goods in the supply chain are what really impact the prices that the consumer sees on the shelf.

Pineau adds that the impact of these changes at the consumer level are minimal, citing information from Consumer Reports that suggests that mandatory GMO labeling “would cost consumers $2.30 per year, less than a penny per day (4).” She says that outside factors such as shopper demographics, brand competition and cost of goods in the supply chain are what really impact the prices that the consumer sees on the shelf.

Fabricant takes a different perspective, believing that if mandatory labeling becomes law “there will likely be an increase in prices due to added costs throughout the entire supply chain.” He adds that the magnitude of this increase is dependent on exactly how labeling is implemented. “If there were to be a patchwork system of labeling (a different label for each state), then the costs would increase exponentially more and interstate commerce would be greatly impacted,” he says.

The next part of the question is whether or not non-GMO leads to increased costs for reasons outside of labeling. Brown brings things back to the beginning, explaining, “Historically, GMO foods were designed partially to reduce costs associated with growing specific crops like corn, cotton and soybeans. If non-GMO crops use more water, are more susceptible to disease and have a longer growing time, then simple costs will dictate a higher price point.” However, while this may be the case, she points out that immediate consumer cost is just one of many issues orbiting GMOs, and factors such as environmental impact mean that sustainable farming practices and what they mean for the future may be worth a higher price point in the short-term.

The level of cost increase may vary depending on the type of product. Warady says, “We found that we were able to make the change to a 100% non-GMO product line without having to raise our costs. Did it cost us a bit more to produce the products? Yes. Did we need to pass this on to the consumers? No.”

Lahrman says, “There is no doubt that it costs time and money to validate products as Non-GMO Verified through a third party, and organic and non-GMO ingredients are generally more expensive.” However, similar to Brown, he sees this as a short-term sacrifice with a worthy result. “The consumer preference for non-GMO foods is a macro industry shift, and over time this will bring more competition among ingredient suppliers and manufacturers who choose to compete in the Non-GMO Verified space,” he explains. In fact, this may already be in play to a degree. A Nielsen study of 30,000 consumers cited by Gamoning said that 80% of those surveyed were willing to pay more for non-GMO foods. WF

Published in WholeFoods Magazine, October 2015

References

References

1. Health Focus International, “Global Shopper Views on GMOs,” www.healthfocus.com/hf/global-shopper-views-on-gmos, accessed 8/20/15.

2. The Non-GMO Project, About Page, http://www.nongmoproject.org/about/, accessed 8/20/15.

3. L. Schinasi and M.E. Leon,” “Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma And Occupational Exposure To Agricultural Pesticide Chemical Groups And Active Ingredients: A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11(4), 4449–4527 (2014).

4. ConsumerReports.org, “GMOs and Food: Do You Know What You Are Eating?” www.consumerreports.org/cro/news/2014/10/gmos-and-food-do-you-know-what-you-are-eating/index.htm, accessed 8/20/15.