"We thought, because we had power, we had wisdom.” – Stephen Vincent Benet

Two years ago in this column, I warned our readers about the proposal of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to effect its first major changes to nutrition and supplement labeling in more than 20 years. The FDA was proposing “to update the Nutrition Facts label for packaged foods to reflect the latest scientific information, including the link between diet and chronic diseases such as obesity and heart disease. The proposed label also would replace out-of-date serving sizes to better align with how much people really eat, and it would feature a fresh design to highlight key parts of the label such as calories and serving sizes” (1).

I cautioned that the FDA planners were still stuck in the past, oblivious to recent advances in nutritional knowledge and that, more alarmingly, the FDA’srealhidden agenda was one that could be both dangerous and threatening to your very health. That has not changed. The FDA isstillstuck in the past, as most government agencies are since they are slow to react to change. A long-overdue increase in the daily value (DV) for Vitamin D is one of the few exceptions here.

On May 27, 2016, the FDA issued two Final Rules on nutrition labeling for foods and dietary supplements. Published in theFederal Register, at 259 and 48 pages respectively, these two rules make significant changes in labeling of conventional foods and dietary supplements with some updating of nutritional values (2).

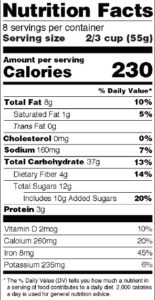

The New Label Spotlights Calories and Serving Size The rules dictate numerous formatting and placement changes to the existing Nutrition Facts panel—including the display of calories. Because the FDA is still stuck in the old nutritional paradigm that says calorie-counting will control obesity rates, the new rules shove the calorie number in consumers’ faces with a much larger and now boldfaced typeface (See figure 1).

So, too, with the “Serving Size” number, which is greatly enlarged so that consumers cannot miss it. The belief here is that consumers actually pay attention to serving sizes declared on labels when deciding how much food to eat. Aside from those who work in this industry, or who are OCD calorie counters, who among us can honestly say that we ever gave any consideration whatsoever to serving size when deciding how much food in a package to eat? I know that I haven’t. I eat until I am full, or until the package is empty.

Moreover, in yet another real-world application of the Law of Unintended Consequences, these changes will not generally help Americans fight obesity by focusing attention on calories and serving size; the changes will actually distract consumers from other, real nutritional issues: such as the nutritional “density” of the food (i.e.,whether or not it is rich in vitamins, minerals and other nutrients) and whether artificial sweeteners such as aspartame and other true fatteners are present. Consumers will continue drinking their super-sized diet colas, secure in their FDA-supported fantasy that losing weight is all about quantity (calories) and not quality.

The New Label Has Larger Serving Sizes As the FDA stated when it first began this rulemaking process, “What and how much people eat and drink has changed since the serving sizes were first put in place in 1994. By law, serving sizes must be based on what people actually eat, not on what people ‘should’ be eating.”

In this respect, the FDA talks good sense about wanting to “present calorie and nutrition information for the whole package of certain food products that could be consumed in one sitting.” A single serving of ice cream, for example, would no longer be a half cup but rather a full cup.

The problem—once again—is that most people do not pay attention to serving sizes when they eat. They pay attention to their appetite. A “serving size” is whatever it takes to fill them up. Yes, it does make sense to increase the serving sizes in light of “modern” eating habits, but will that achieve the FDA’s stated goals of reducing obesity and heart disease? Unlikely. But at least this change is a step in the right direction of recognizing that Americans are eating significantly larger food portions.

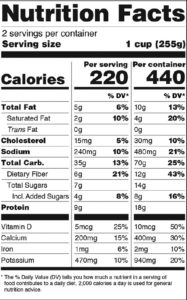

The New Label May Require Dual Columns With its focus on serving size, the FDA has also decided that nutrition-facts labels for packages that contain 1-2 servings must declare calories and nutrients as if the package contains one serving only. However, for those food-and-drink products such as a pint of ice cream, which are larger than a single serving but could be consumed in one or several sittings, “dual column” labels must be used to show the amount of calories and nutrients in both a “per serving” and “per package” (or ”per unit”) display (See figure 2).

The New Label Mentions “Added Sugars" The old label requirement is for a mandatory declaration of total sugar only. But, Americans currently eat 60% more sugar than the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends and the FDA has tackled the problem with a mandatory declaration of “Added Sugars.” (3) This tracks, by the way, with the discussion at Codex Alimentarius meetings about declaring “added sugars” on the food labels of its member States, even though that has not yet become a Codex label requirement.

Still, as admirable as this effort might seem to be, once again, it will have the public looking in the wrong direction—looking for “added sugars” instead of also looking for zero-calorie artificial sweeteners that are brain-damaging and far less healthy. Dangerous additives like aspartame and sucralose will not be highlighted in this revised Nutrition Panel and consumers will be misled into thinking that their selection of a zero “Added Sugars” product is healthier.

The New Label Deletes “Calories from Fats” Recognizing that thetypeof fat rather than theamountis the key, the FDA has correctly proposed to delete “Calories from Fats” from the Nutrition Facts panel. Labels will, however, continue to require “Total Fat,” “Saturated Fat,” and “Trans Fat.”

Fluoride and Choline to be Declared Although an increasing number of people are realizing that fluoride can be a public health hazard, especially when added as mass medication to our water supplies, others still think that fluoride is, as the FDA states, a nonessential nutrient “but one with well-established benefits for the teeth.” Never mind that fluoride displaces beneficial selenium in the body, and certainly never mind that the fluoride–cavity connection is tenuous at best. With this outdated view of fluoride in mind, the FDA has ruled that fluoride content may now be disclosed—voluntarily—on food labels ormustbe declared on the label if added or claims are made for its presence.

Of course, for those of us who would prefer toavoidfluoride, this label change is not unwelcome at all. It is just ironic that many of us will use the fluoride label declaration as a means ofavoidingits intake rather than ensuring it as the FDA has envisioned.

As for the nutrient choline, it too must be declared when added to a product or if a claim is made about it. Or, it can be voluntarily disclosed in all cases where it is present.

Replacing Some Nutrients with Others

The rules require the declaration of potassium and vitamin D in place of vitamins A and C, since the FDA has decided that the former are currently more important than the latter for public health. As the FDA states, “some in the U.S. population are not getting enough of [potassium and vitamin D], which puts them at higher risk for chronic disease. Vitamin D is important for its role in bone health. Potassium is beneficial in lowering blood pressure.”

Although dethroned and no longer required on labels if the proposed changes become final, vitamins A and C can still be voluntarily declared by manufacturers. The FDA has its flavors of the decade and these two are no longer them.

Similarly, the rules sort out the tangle of names for folic acid, folate, and folacin, the last of which may no longer be used synonymously with folate. So, say goodbye to folacin. And you may use folate and folic acid, but only where appropriate (see the rules for further details).

Also, manufacturers must declare the actual amount, in addition to percent DV of vitamin D, calcium, iron, and potassium. They can voluntarily declare the gram amount for other vitamins and minerals.

Say Goodbye to International Units As previously announced, the rules abandon the International-Unit potency designations for Vitamins A, D, and E, and replaces them with mcg RAE for Vitamin A, μg for Vitamin D, and mg α-tocopherol for Vitamin E. Section 101.9(c)(8)(iv) of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act will be amended; and those of you who, like me, were so accustomed to visualizing these vitamins potencies in IU potencies will now have to adjust to the European metric potencies.

To be fair, the change does make for more consistency with the metric potencies for all other vitamins and minerals on the label. But perhaps ominously, this change will also harmonize U.S. measures to European and Codex measures, which makes comparisons easier but which also dovetails very dangerously with plans to harmonize American vitamin-and-mineral potencies to those of less enlightened jurisdictions.

The Revised Footnote

On Nutrition Facts panels, there has been a longstanding requirement to footnote the term “% Daily Value.” The final rule, at § 101.9(d)(9), now requires a lengthier footnote defining “% Daily Value” on a Nutrition Facts label. Except for certain exemptions allowed for calorie-free foods and drinks, that footnote must read: “* The % Daily Value tells you how much a nutrient in a serving of food contributes to a daily diet. 2,000 calories a day is used for general nutrition advice.” Unfortunately, this revision takes up yet further valuable label space in a vain attempt by the FDA to clarify the meaning of its previous footnote.

Record-keeping Required The rules mandate that manufacturers create and maintain records that will support the fiber, added nondigestible carbohydrate, added sugar, vitamin E, and folic acid levels claimed on the label. Whether determined analytically or through calculations documented in appropriate records, manufacturers are obligated to provide nutrient information that is not false or misleading.

The FDA states, “Records used to verify nutrient content could include various types of batch records providing data on the weight of certain nutrient contributions to the total batch, records of test results conducted by the manufacturer or an ingredient supplier, certificates of analysis from suppliers subject to initial and periodic qualification of the supplier by the manufacturer, or other appropriate verification documentation that provide the needed assurance that a manufacturer has adequately ensured the food or ingredients comply with labeling requirements. The records submitted for inspection by FDA would only need to provide information on the nutrient(s) in question. Information about other nutrients can be redacted if necessary to ensure confidentiality of a food product formulation.”

Even Worse, a Blow to Nutrient Levels At the same time as attention is focused on the numerous format changes, the FDA is slowly but surely harmonizing our vitamin-and-mineral levelsdownto those of Codex Alimentarius. Not 100%, but mostly.

Ever since the National Health Federation’s victory at the 2009 Codex Committee on Nutrition and Foods for Special Dietary Uses meeting (where an Australian-led attempt to reduce, across the board, vitamin-and-mineral Nutrient Reference Values [NRVs] was rebuffed), Australia and other Codex delegations have continued pushing their anti-nutrient agenda. Conspicuously silent during these debates has been the U.S. delegation. Did it have its own agenda? Was Australia the American lapdog, allowing America to remain quiet while doing America’s bidding?

Interestingly enough, Codex Alimentarius is mentioned in the FDA’s Final Rules multiple times, as it was in the original Proposed Rulemaking, where, two years ago, the FDA proposed to dumb down our DVs to abysmally low Codex levels for no fewer than eight vitamins and minerals, while one (folic acid) already matches the Codex NRV and two others are within spitting distance. In the case of biotin, FDA proposed to cut its DV by 90% in order to match the Codex value (4).

Going back to at least its October 11, 1995, pronouncement in theFederal Register, the FDA has made no secret of its intention and desire to harmonize its food laws with those of the rest of the world. The two rules and their label changes simply prove that this intention is still very much alive. Were those global standards for vitamins and minerals higher than our own, then such a change might be advisable, even admirable. But we all know that most of the rest of the worlddisdainssupplementation, either separately or in foods, and since these proposed label changes for DVs apply equally to the Supplement Facts panel as they do to the Nutrition Facts panel, they are very dangerous changes indeed.

Bear in mind that in at least two instances, the Final Rules diverge from Codex. “Added Sugars” are not required to be disclosed by Codex, yet; and the new DV for vitamin D has actually been increased to 20 mcg (800 IUs) per day, which is a very welcome change and perhaps a harbinger for what will come at the Codex Nutrition Committee meeting to be held in December 2016, in part to set a DV for this very vitamin.

Regardless, there is a connection between these FDA-proposed DVs and the ultimate, maximum upper permitted levels, with harmonized global standards paving the way forreducedvitamin-and-mineral levels whether in pill form or food form.

Compliance with these Changes The FDA has set the effective date for the rules as July 26, 2016. By the time you will read this, then, the rules will be effective. However, food manufacturers will have two years (that is, until July 26, 2018) to bring their labels into compliance with the Final Rules, unless the company has less than $10 million in annual sales, in which case those smaller companies will have an additional year to comply.

The rules do not specify exactly what must be done as of the compliance date (July 26, 2018 or 2019). Does that mean that all productson the marketas of those dates must be label compliant? Or does it mean simply that all products beingintroduced into the marketas of those dates must be compliant? One approach would require manufacturers to update and apply the new labels in advance of the compliance date while the other does not. If we look to a prior label-change experience under the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act of 1990, then the FDA will accept the latter approach to compliance.

The rules will be a boon for food-and-drug lawyers and consultants as companies turn to law firms such as Venable LLC and others to help with reformatting labels and adding in the information now required by the FDA. Please remember that this article is but a brief overview of many but not all of the label changes. In 307 new pages of bureaucratic rules, there is considerable more detail than can be covered in these few pages. WF

A graduate of the University of California at Berkeley Law School, Scott C. Tips currently practices internationally, emphasizing Food-and-Drug law, business law and business litigation, trade practice, and international corporate formation and management. He has been involved in the nutrition field for more than three decades and may be reached at (415) 244-1813 or by e-mail at scott@rivieramail.com.

End Notes

- FDA News Release, “FDA Proposes Updates to Nutrition Facts Label on Food Packages,” Feb. 27, 2014, www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm387418.htm. See also “Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels,” 79 Fed. Reg. 11879-11987, March 3, 2014, www.federalregister.gov/articles/2014/03/03/2014-04387/food-labeling-revision-of-the-nutrition-and-supplement-facts-labels.

- “Food Labeling: Revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels,” 81 Fed. Reg. 33741-33999, May 27, 2016, https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2016/05/27/2016-11867/food-labeling-revision-of-the-nutrition-and-supplement-facts-labels and “Food Labeling: Serving Sizes That Can Reasonably Be Consumed at One Eating Occasion, etc.” 81 Fed. Reg. 34000-34047, May 27, 2016, at https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2016/05/27/2016-11865/food-labeling-serving-sizes-of-foods-that-can-reasonably-be-consumed-at-one-eating-occasion. See also “Changes to the Nutrition Facts Label,” FDA website, at http://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/LabelingNutrition/ucm385663.htm.

- See also Gasparro A & Esterl M, “FDA Approves New Nutrition Panel That Highlights Sugar Levels,” The Wall Street Journal, May 20, 2016, at http://www.wsj.com/articles/fda-approves-controversial-changes-to-nutrition-facts-panel-1463750195.

- 79 Fed. Reg. 11879-11987, supra, Table 2 at page 11931.

Published in WholeFoods Magazine August 2016