The average raw materials supplier has a lot of responsibility on its shoulders. Before they can say “mission accomplished,” they must be sure they are investing in the right ingredients, sourcing those ingredients from the right people, testing them for quality and purity with the most stringent and up-to-date methods available, and doing it all while remaining in strict compliance with current manufacturing standards and industry regulations. Then, they have to keep their prices low enough for finished product manufacturers to be interested.

Industry experts, executives and scientists will give us the low down on what suppliers are talking about, and how their companies make it through the minefield to profitability, while maintaining sustainable and r esponsible practices. Natural supply is a complex and a daunting task, and these are the people who make it happen, turning the world’s resources into the natural, healthful products that we all enjoy.

esponsible practices. Natural supply is a complex and a daunting task, and these are the people who make it happen, turning the world’s resources into the natural, healthful products that we all enjoy.

Where Does it All Come From?

Safety vs. price. Sourcing responsibly is made easier when raw materials suppliers establish a good working relationship with their own supplier and growers. “This is hard to do if you are not willing to stick with a supplier long enough to build that relationship, and jump from supplier to supplier searching for the best price,” says Micah Osborne, president of ESM Technologies, Carthage, MO.

“Certainly, everyone knows there have been some major safety and health issues coming out of China in recent years. In my opinion, this has been because many dietary supplement manufacturers in the natural products industry have shopped for price alone,” echoes Bob Green, president of Nutratech, Inc., West Caldwell, NJ.

Bringing materials in-house in their original state is one way to oversee product quality and safety. “We choose to bring in our raw material in as raw a form as possible in order to gain better control over the process. Our company takes whole broken eggshells from the egg products (or egg breaking) industry and then does all of the processing in house from start to finish,” Osborne says.

But for those without the facilities, hiring a third party may be the only solution, making the practice less cost effective, according to Green. “If an ingredient supplier has manufacturing capabilities in the United States, it might make sense to bring raw materials into the country rather than process them abroad. But if you’re bringing whole herbs and botanicals into the United States and using an outside manufacturer for processing, you’re just spending money unnecessarily,” he says.

according to Green. “If an ingredient supplier has manufacturing capabilities in the United States, it might make sense to bring raw materials into the country rather than process them abroad. But if you’re bringing whole herbs and botanicals into the United States and using an outside manufacturer for processing, you’re just spending money unnecessarily,” he says.

Green says his company’s materials sources in Asia are trained in standardized practices that test for authenticity, purity, potency, stability, microbial load and more. All of this must be completed before materials are shipped to the United States. Once its branded ingredient arrives in the country, it goes under quarantine until it is tested again by a third-party laboratory. “In my opinion, this is the only responsible way to source ingredients from Asia,” Green says.

Donna Battaglia, director of sales, Isabel Elias-Castro, Global Export Group vice president and Jessie Rose, product specialist of proprietary branded ingredients, of Maypro Industries, Purchase, NY, spoke to WholeFoods about their company’s long-standing, loyal relationships with their sources. “Our offices, strategically located overseas, allow us to have strong communications with our manufacturers and to audit their facilities on a regular basis,” they say.

If quality assurance is the primary goal, geography should not make a difference in creating partnerships with sources. “Evaluation and audit protocols remain the same whether the manufacturer is in the United States or South Korea. The downside to any off-shore location is distance, but the level of expectations and follow through remains the same per country of origin,” says Michael Jeffers, president of Helios, Santa Fe, NM.

If quality assurance is the primary goal, geography should not make a difference in creating partnerships with sources. “Evaluation and audit protocols remain the same whether the manufacturer is in the United States or South Korea. The downside to any off-shore location is distance, but the level of expectations and follow through remains the same per country of origin,” says Michael Jeffers, president of Helios, Santa Fe, NM.

The transparency of a sourcing partnership may foretell its future success. Says Chris Haynes, director of sales for ESM Technologies, “Our greatest challenge was finding suppliers who were willing to work with us and allow us to hold them accountable; this requires a very open relationship that a lot of suppliers just are not comfortable with.”

Sourcing has issues. Good old competition and scarcity is an enduring factor in sourcing raw materials. “It has become tougher to source in the 21st century than it was in the 20th, even though communications have so greatly improved,” opines Paul Flowerman, president of P.L. Thomas & Co., Inc., Morristown, NJ. This is because, he believes, U.S. companies must compete not only with Japan and Europe, but also with the resource-hungry “BRIC” countries (Brazil, Russia, India and China), which contribute to increasing the scarcity of raw materials and lengthening lead times.

Eric Anderson, vice president of sales and marketing for Aker BioMarine Antarctic US, Seattle, WA, explains that while many companies strive to secure the safety and purity of their sources, some must ensure that the source itself remains viable. “Within krill harvesting, sustainability is the core consideration. The world’s marine resources are not inexhaustible,” Anderson says. Antarctic krill catches, he explains, are regulated by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), and represent only a tiny fraction of the total krill biomass. Still, as with all marine harvesting in recent times, sustainability is a sticking point, and a license from CCAMLR is required for any fishery harvesting krill.

inexhaustible,” Anderson says. Antarctic krill catches, he explains, are regulated by the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR), and represent only a tiny fraction of the total krill biomass. Still, as with all marine harvesting in recent times, sustainability is a sticking point, and a license from CCAMLR is required for any fishery harvesting krill.

Other suppliers find themselves working with a unique scenario when it comes to materials procurement. “We are fortunate to use starting material from one unique source, the maritime pine tree of Les Landes, in gascony, France. The forest is governed by French forestry laws and meets their stringent environmental standards,” says Victor Ferrari, CEO of Horphag Research, suppliers of an ingredient (Pycnogenol) distributed to the North American market by Natural Health Science, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

Another potential sourcing issue to be aware of is the tendency for source material to undergo small physical changes with big implications. Sources should also be held accountable and screened based on their reputation for fulfilling delivery commitments, according to Richard Mihalik, director of quality assurance for National Enzyme Company, Forsyth, MO. “Performance of materials in production should be monitored, since subtle changes in physical properties sometimes lead to manufacturing difficulties. Price and ontime delivery should also be continuously monitored,” Mihalik says.

In summary, suppliers must question their values from the outset of the materials procurement process. This is because, according to one expert, quality assurance starts, well, at the beginning. “It all starts with the product as it is harvested—if you have poor products in your harvest, it will be difficult, if not impossible to translate that into a product that is going to meet our company’s standards,” says Jason Soltis, Esq., regulatory affairs representative for Ecuadorian Rainforest, LLC, Belleville, NJ.

Ssatisfying the Client: Quality and Testing

(Current) good manufacturing practices. The rules of the road are not what they used to be, and every supplier is realizing the need to get up to speed for themselves. Current good Manufacturing Practices (cGMPs) have come a long way from their inception through June 2010, the date by which small companies (20 employees or less) had to get i n line with new “final rule” GMPs for dietary supplements (1). While the final rule does not apply to raw materials suppliers directly, the indirect impact has been substantial, so it’s an issue fresh on the lips of suppliers everywhere.

n line with new “final rule” GMPs for dietary supplements (1). While the final rule does not apply to raw materials suppliers directly, the indirect impact has been substantial, so it’s an issue fresh on the lips of suppliers everywhere.

The dust hasn’t yet settled from all of the adjustments, and countless hours of training, which many manufacturers have undergone to become GMP compliant and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)- inspection ready. Suppliers have made haste to align themselves with the cGMPs themselves, through ingredient testing and other documented assessments of quality. This is in order to assure manufacturers that their raw materials will meet the necessary standards where cgMPs legally apply, in the realms of manufacturing, packaging, labeling and storing.

Soltis weighs in on the seismic shift the emphasis on GMPs has caused, and explains that documentation and breaking down the information in the standards themselves have been two areas of concern. “Under the GMP regulations, there is a saying that if it’s not recorded, then it did not happen,’” he says. It is one thing for a supplier to make the effort to make compliant ingredients, and another to have the properly documented, tangible proof to present to manufacturers. Adds Soltis, “It’s important because during an internal, external or FDA audit, the documentation holes can create havoc for a company.”

When it comes to making sense of cGMPs, Soltis says, “You have almost 800 pages of comments and regulations, but that amount of information must be broken down into easy to explain and implement formulas. The information is sometimes vague or confusing, but you must present it in a clear, no-nonsense way that your employees can easily implement.”

Scott Steil, president of Nutra Bridge, Shoreview, MN, thinks that the advent of more stringent GMPs has been worth the price of admission. “There has been an exponential increase in testing of raw materials with the implementation of GMPs. Obviously, this adds incredible costs to the manufacturing process, but it is helping improve the quality of products that consumers buy and is eliminating some of the companies and the use of products that do not meet specifications,” Steil says.

Others agree about the effect of GMPs on testing in recent years. “Manufacturers, retailers and consumers are very concerned with stability of the finished product, safety, toxicity, shelf life, authenticity, country of origin, non-gMO, allergen free, pesticide free and sterilization methods,” says the Maypro team. Sterilization, they explain, is done in part to ensure that materials have not been irradiated or treated with ethylene oxide, a known carcinogen that may cause cancer in humans (2).

explain, is done in part to ensure that materials have not been irradiated or treated with ethylene oxide, a known carcinogen that may cause cancer in humans (2).

Testing…1…2…3. Striving for quality is not a recent endeavor. For suppliers and finished product makers, ensuring that materials and ingredients are authentic has always been a priority. Now, with cgMPs, this level of assurance is a necessity, and not a just a virtue, as Shaheen Majeed, marketing director, Sabinsa, East Windsor, NJ attests. “Some 483s have been issued, remarking on certain companies’ inabilities to identity test materials they are using prior to and in manufacturing,” he says. FDA’s Form 483 is a routine notification used by the agency to document and communicate concerns discovered during factory inspections.

Assay testing, performed to confirm the active constituent of an ingredient, is not only an important aspect of product development, but also is a key step in the process of standard ingredient testing. Other commonly utilized tests include USP (United States Pharmacopeia) pesticide testing, microbiological screens and PPSL (pulsed photo-stimulated luminescence) testing to confirm the absence of gamma irradiation. Food irradiation is a controversial concept, as it is usually performed to ensure the safety of food, but some critics deem it an unproven, potentially unsafe procedure. Therefore, some natural suppliers may steer clear of the irradiation route and test for its absence.

Flowerman gives kudos to third-party laboratories with good reputations, saying, “Great equipment is useless without a great technician.” His company outsources testing to the best laboratories they can find, using different lab facilities  for different tests and relying on their expertise. “We and our suppliers also must be proactive, operating on the premise of ‘you don’t know what you don’t know,’ meaning that potential contaminants, shelf-life issues or other quality problems specific to the particular ingredient must be anticipated and checked,” Flowerman says.

for different tests and relying on their expertise. “We and our suppliers also must be proactive, operating on the premise of ‘you don’t know what you don’t know,’ meaning that potential contaminants, shelf-life issues or other quality problems specific to the particular ingredient must be anticipated and checked,” Flowerman says.

Ken Paydon, director of laboratory services for National Enzyme Company, says suppliers should check up on the credibility of thirdparty labs before choosing, and seconds the idea of using more than one. “It is important to look for third-party accreditations (such as International Organization for Standardization 17025). It is also important to know that third-party labs each have their own set of expertise, and so one-stop shopping may not be possible,” he says. ISO 17025 is the basic international standard for laboratory testing competency.

One trending area is heavy metal contamination testing. “This testing is commonly done utilizing inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and is reported as parts per million (ppm) or parts per billion (ppb) of the contaminating metals,” explains Kevin J. Ruff, Ph.D. and director of scientific and regulatory affairs for ESM Technologies. According to Ruff, this technology is very expensive, so most ingredients will go to a third-party lab that specializes in this type of testing.

Dan Murray, vice president of business development for xsto Solutions, LLC, Morristown, NJ, thinks that testing needs to bring ingredient bioavailability into the equation. “Just because we can recover the ingredient in an assay does not mean humans can absorb and utilize the ingredient for its nutritional benefits,” Murray says.

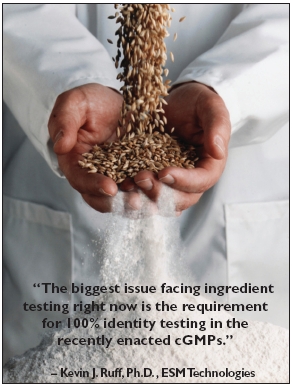

The consensus focal point of ingredient testing these days, though, is very simple: What exactly is it? “The biggest issue facing ingredient testing right now is the requirement for 100% identity testing in the recently enacted cgMPs,” Ruff says. High-tech tests abound for this purpose, including Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). “FTIR identifies the fingerprint of individual raw materials, helping distinguish various raw materials from others,” says Ron Udell, president and CEO, OptiPure/Kenko International, Inc., Los Angeles, CA.

Companies take various measures to ensure both product and facility safety. Independent factory audits and FDA/USDA standards like Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP) are taken up by many suppliers. HACCP are mandatory for meat and juice manufacturers and voluntary for other food products, but some companies still opt to follow them as safety guidelines.

For some suppliers, it makes sense to care how their ingredients fare down the line of production. This starts with formulating for optimal stability, and testing for stability as well. This is a priority when formulating nutraceuticals, according to Paul Dijkstra, CEO of InterHealth Nutraceuticals, Benicia, CA. They check to see how their ingredients hold together after manufacture, when it counts. “Stability data confirming the ingredient has retained its structural integrity for the life of the product is needed to ensure efficacy,” he says.

For suppliers invested both personally and financially in the reputation of the industry, testing provides the added benefit of weeding out bad players. “I’ve been in the industry since the early 1990s and have seen ingredients that do not meet specifications, as well as products that are outright adulterated and/or contain no actives!” says Anderson. “We also see today a ‘sleight of hand’ with some suppliers, labeling a product as one ingredient, while delivering a blended concoction of other ingredients from other, non-native sources, confusing the industry and consumers alike,” he adds.

Anderson believes that historically, this type of cheating has been too easy, and that the fully enacted cGMPs haven’t done as much as expected in curbing the cheaters thus far. It is incumbent upon serious suppliers to properly test and label their raw materials, according to Anderson. “Ultimately, if the consumer does not receive the promised benefits, the ingredient will fade in the market,” he says.

Anderson believes that historically, this type of cheating has been too easy, and that the fully enacted cGMPs haven’t done as much as expected in curbing the cheaters thus far. It is incumbent upon serious suppliers to properly test and label their raw materials, according to Anderson. “Ultimately, if the consumer does not receive the promised benefits, the ingredient will fade in the market,” he says.

Testing, of course, gets product-specific where necessary. A Nutratech, Inc. branded ingredient, for instance, is screened to check that it only contains psynephrine (the stable isomer of synephrine) and not the undesirable m-synephrine.

Similarly, botanical ingredients “pose a unique challenge to the industry and more sophisticated analytical procedures such as thin-layer chromatography (TLC) are needed to confirm the ‘identity’ of these ingredients,” says Joe Mitchell, vice president/ qA qC services, Pharmachem Laboratories, Inc., Kearny, NJ. Christian Artaria, marketing director and head of functional food development, Indena S.p.A., Milano, Italy, says his company “is concerned about the blatant adulteration of particular botanical extracts, such as bilberry and pygeum, that is still too prevalent in our industry.”

The lesson for manufacturers is that specific ingredients have specific testing requirements, and excellence in this area requires expertise on the part of the supplier. Learning the scientific and safety ropes in a market segment, especially for a new and poorly understood ingredient, is essential in working with the supplier and assessing their certificates of analysis (COA).

Requirements for testing a given product are ever-changing, and new angles will always crop up, according to Mitch Skop, senior director/new product development with Pharmachem Laboratories, Inc. It is up to suppliers to stay ahead of the curve. “This has become an overwhelmingly enormous question over the past few years. With new and unexpected issues like melamine contamination forcing their way into our quality Assurance vocabulary and systems, we’re constantly learning,” Skop says.

The bottom line on quality is that manufacturers, retailers and consumers are looking for reassurances of an ingredient’s/ product’s safety. “Is it ‘clean’ and without contaminants?,” asks green, “Will it live up to the manufacturer’s label claims? As an ingredient supplier, it’s our job to deliver these reassurances, so the reputations—for accuracy, reliability, etc.— of the testing labs we use are essential.”

|

WEB EXCLUSIVE: Marketing as a Supplier Product promotion isn’t only for finished products. Branded ingredients need a high profile too, and even commodities have to receive industry support to maintain or increase market position (one need only recall ‘Got Milk?’ as an example). According to Bob Green, president of Nutratech, Inc., West Caldwell, NJ, it all starts with the bread and butter of a brand. “Marketing of a branded ingredient starts with the name and logo,” he says. Patents, and the legal defense of those patents, are often required to solidify your branded ingredient and its unique functions. “We look at the basic components of what would make for a good patent—an ingredient’s composition, its process of manufacturing or even the use of the ingredient,” says Shaheen Majeed, marketing director, Sabinsa, Payson, UT. If any of these can be patented, Majeed says his company takes a keen interest in pursuing it. “A branded ingredient also requires a robust scientific portfolio to back up its safety and efficacy,” Green says, adding that general industry advocacy is also essential. He cites the example of his company, which he says is actively involved with issues facing the natural products industry, and in the proceedings of industry associations like the American Herbal Products Association (AHPA) and American Botanical Council (ABC). Since the supplier is the one funding research, it is usually left up to product marketers to leverage that research in finished-product claims. “We request that our customers around the world comply with local regulations and ensure that their marketing and communication are in line with the law,” says Victor Ferrari, CEO of Horphag Research, who are makers of a French pine tree bark extract supplement that is supplied to the North American market by Natural Health Science, Inc., Hoboken, NJ. “Our scientific bibliography provides a variety of marketing and health claims,” says Ferrari. These claims are how the finished products are sold, but it is a delicate area that must be handled responsibly to avoid regulatory measures. “Simply making a product is much different than developing a market for a product,” says Sid Shastri, M.Sc., product development manager for Kaneka Nutrients, Pasadena, Texas. According to Shastri, due diligence in the following areas is necessary before attempting to move a branded raw material to market: |

Research Gold

Suppliers recognize that scientific research is the backbone of their products’ ability to succeed on the market, especially when it comes to functional ingredients. To achieve that success, investment gold must be put forth in support of gold standard research. Only then can suppliers hope that satisfied, healthy consumers catch on to the product. Then, the supplier ends up with more gold than they started out with, and this is the goal of product development. But investment is a risky enterprise, so it pays to do it right, insiders say.

“Good clinical research is defined by using randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled studies that are published (offering a third-party review of the data) and that show statistically significant results of primary endpoints,” according to Steil. These elements add up to what is known in the scientific community as the gold standard of research. Steil contends that the decision process when it comes to research investment is simple: What does the company need to know or prove about its product, and what is the market (a.k.a. the consuming public) asking to be studied in the current environment?

To answer these questions, suppliers must turn to consulting firms or their own expert staff, to assess the likelihood that a product has the potential winning combination of safety and efficacy. Once research has been completed, companies must then assess the need to submit their product for New Dietary Ingredient (NDI) status. For new ingredients, FDA review must take place before the material is eligible to be brought to market. If a product was sold before the Dietary Supplement and Health Education Act (DSHEA), it can be marketed to companies that sell finished goods without a problem.

The product development stage can take up to 18–24 months, with the end result ideally being a product that the consumer can purchase and use to improve overall health and quality of life, according to Steil. “The whole process can take up to three to six years and require several million dollars of investment, which makes good business sense for serious companies committed to long-term presence and success in the marketplace,” he says.

Flowerman offers the criteria his company considers before ever getting involved with a product and backing its research:

• The target ingredient must be demonstrated as safe within the stipulated usage level with a wide margin of safety at higher usages.

• A target ingredient must provide a compelling benefit which is highly likely to be appreciated by the market as “best in class.”

• The scientific partner must be credible and great to work with.

• The ingredient is “experiential” in effect and likely to test out in a statistically significant way.

In other words, regarding the last criterion, suppliers should look for ingredients whose health benefits will be felt in a major way. If it doesn’t have the potential to have an appreciable effect, it may not make a dent in the market and may not be worth a supplier’s precious investment gold. Potential for diverse application is always a plus as well. “Ingredients that work in dietary supplements and in food and beverages can have an advantage in the market,” says Dijkstra.

It isn’t easy to clearly demonstrate the benefits of a dietary supplement, according to Joosang Park, Ph.D., vice president of scientific affairs, BioCell Technology, LLC, Newport Beach, CA. “From an industry perspective, performing a successful trial in a healthy population poses a challenge primarily due to the lack of reliable biomarkers or primary endpoints” resulting from supplement use, he says.

It is paramount that suppliers spend investment dollars wisely, but they don’t always have to do it alone. “Our manufacturers fund the research, while we provide guidance on the commercial value of the research and help manage the studies with contract research organizations (CROs) and university researchers,” says the Maypro team. CROs are a big part of the new research regime in many industries. As the product development landscape became more complex and demanding, the need arose, first in the pharmaceutical and then in other industries, for the outsourcing of research.

Of course, the research itself must be up to snuff, scientifically speaking. “Times are changing and if a prospective supplier cannot promise these types of standards, then the supplier could find itself under scrutiny by the FDA and FTC,” says Jeffers. Marketing and the research that backs it can get in hot water for not validating structure and function claims. The research may be flawed, or there may simply be a lack of proper clinical studies, Jeffers says.

Before moving to human clinical trials, “first ‘proof of concept’ has to be provided via in vitro and in vivo studies using an animal model. The elements necessary for the first stage include target cells or tissues affected by ingredients, dose/response relationship, bioavailability, and potential toxicity,” says Park.

Since the two main endpoints suppliers seek to verify in a product are safety and efficacy, studies are usually organized to analyze key areas within these separate facets of a given ingredient. “This means having numerous studies to demonstrate safety (e.g., cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, acute oral toxicity, etc.), which ideally results in a GRAS (generally recognized as safe) opinion,” says Ruff, adding that for efficacy, multiple studies (e.g., in vitro, animal and human) will ideally culminate in gold-standard human trials.

Integrity is a quality that suppliers must also lend to the research they fund. Supplier-funded researchers should be given the freedom to publish results without the prior approval of the supplier, according to Michael Cleary, National Enzyme Company’s vice president of innovation and development. Subject groups in product studies should be large and diverse enough to encompass the range of demographics represented in the North American market.

As was noted at the outset of this discussion, suppliers cannot underestimate the importance of quality research. “Clinical substantiation should be the backbone of our industry. This is the basis of allowing marketers to truthfully make claims—a promise to the consumer for real health benefits,” says Anderson.

Generally Recognized: Regulatory Wrap-Up

Generally Recognized: Regulatory Wrap-Up

You don’t mow it and you don’t water it, but it’s still GRAS. Achieving the sought-after product status of generally Recognized as Safe is certainly a cause for supplier celebration, so it pays to receive sound advice on navigating the time-honored process. “GRAS status has been around for over 50 years, and it does provide a way for food ingredients to be evaluated for safety by individuals who have appropriate training and expertise. It need not only be done by FDA personnel,” says Robert McQuate, Ph.D., CEO and co-founder of GRAS Associates, Bend, OR. He founded the company in 2005 along with COO Richard C. Kraska, Ph.D., to provide industry companies with general guidance and various types of consultation on the path to GRAS status.

McQuate explains the two paths to a GRAS ingredient. “You can have a self-affirmed GRAS evaluation, and that means that a company can make such a determination with the appropriate credentialed expert panel. Or, the procedures that are being utilized by FDA right now and since 1997 allow for companies that have made GRAS determinations to voluntarily submit them for review by FDA,” he says. GRAS Associates will help convene the expert panels necessary for self-affirmed GRAS, as well as offer advice to companies, early in the process, on commercialization strategies for the ingredient at hand.

According to McQuate, who worked along with Kraska for FDA’s GRAS team in the late 1970s, the understood standard for attaining GRAS status is “reasonable certainty of no harm under the intended conditions of use.” Even though it isn’t legally required, FDA review can provide an additional stamp of approval that companies might want to pursue, if influential customers would feel a greater degree of comfort after FDA files the desired “no comment” for the submitted ingredient. But, once the submission is made, the data surrounding the ingredient become public, which may remove a supplier’s competitive advantage over rival companies.

Additionally, says McQuate, “there is the risk that FDA may disagree with the GRAS determination that an expert panel has made. That’s something that has to be factored in, in making a determination of the strategy as to whether one would submit to FDA or not.” In this case, FDA will produce an issue or question that concerns them about the submitted ingredient, and the notifying company then has the opportunity to clarify or correct the issue. This may cause the company to request the evaluation be ceased until the issue can be dealt with thoroughly.

Additionally, says McQuate, “there is the risk that FDA may disagree with the GRAS determination that an expert panel has made. That’s something that has to be factored in, in making a determination of the strategy as to whether one would submit to FDA or not.” In this case, FDA will produce an issue or question that concerns them about the submitted ingredient, and the notifying company then has the opportunity to clarify or correct the issue. This may cause the company to request the evaluation be ceased until the issue can be dealt with thoroughly.

Toeing the (FDA) line. FDA deals frustration to industry companies when it tries to categorize products in a way detrimental to the supplier or manufacturer. Of concern to natural products suppliers is the chance FDA will deem an ingredient with strong health claims as a drug, not a dietary supplement, and then regulate it as such. Another reason this can happen is a trend cited by Mihalik, having to do with a product’s association with the pharmaceutical industry manual USP–NF (National Formulary). Natural product makers also adhere to the manual as a designation of quality for some products.

“An issue that we see coming up for our products is the reduction of raw material suppliers willing to label their material as conforming to USP or NF monographs. This development stems from FDA beginning to hold raw material suppliers, which label their products as USP or NF compliant, to drug raw material supplier cgMP standards,” says Mihalik. He says that this development could have companies like his searching for new ingredient sources to avoid being reclassified, which could have unforeseen effects on product quality. For companies wary of this happening to them and starting to seek new sources, Mihalik advocates a careful evaluation process and a change control system for a smooth transition.

Another area that FDA has marked for heightened enforcement in the coming months is the pre-94 (pre-DSHEA) lists. Undocumented, and thus illegal, post-94 ingredients will be sought out soon, if FDA is to be believed. Nena Dockery, scientific and regulatory affairs manager for National Enzyme Company, recommends that manufacturers and distributors evaluate the ingredients they are using to ensure that they are, in essence, legal to include in dietary supplements. “This is an area that we all should be watching closely as it could drastically impact the type and variety of products available on the market,” she says.

A watchdog mentality, and a positive attitude toward regulation, may be good for suppliers. “There are still full-page newspaper ads as well as numerous websites that advertise products to prevent and cure various diseases. It will be very difficult to achieve the type of credibility that reputable companies want to command as long as these ‘bad players’ remain an active part of the natural health industry,” Dockery says. Others agree, with Artaria saying, “We believe some enforcement by FDA is needed— particularly on the supply side—that will set an example that economic adulteration of ingredients will no longer be tolerated.”

The push for FDA-qualified health claims for various ingredients is of interest to a range of suppliers, but the uninhibited use of claims in marketing is a thing of the past. “The omega-3 market is fortunate to have a qualified health claim: ‘Supportive but not conclusive research shows that consumption of EPA and DHA omega-3 fatty acids may reduce the risk of coronary heart disease’,” says Anderson. Many claims such as this have been achieved for other ingredients, such as selenium very recently. Suppliers and the manufacturers they work with have witnessed many high-profile cases in the past year, involving mainstream and natural product makers in legal battles with FTC over claims based marketing.

Flowerman cites an international example of claims-based marketing woes, saying “Many Europeans in the food and dietary supplement industries are downright gloomy at the rejection by European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) of the majority of statements about ingredients which have been documented for years.”

Some regulatory situations are more limited in scope, but are nonetheless taken seriously by those affected. “The FDA, FTC and the state of California (for Prop 65) have all stepped up their enforcement action over the last few years,” says Ruff. Proposition 65 mandates that businesses in California print clear warnings for products containing known toxic chemicals from an official list of over 800 offenders. Companies must therefore test for trace amounts of lead and heavy metals that may put their ingredient in violation of the law.

Skop’s reaction to Proposition 65 and regulation like it is one of acceptance and understanding. “As an industry, we have lacked in self-regulation, allowing irresponsible marketers sometimes to make a mess, where we should have intervened for the good of the entire category. That’s why the FTC steps in, sometimes overzealously: to protect the consumer,” he says. WF

References

1. “FDA Issues Dietary Supplements Final Rule,” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, May 28, 2009, http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/ Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2007/ucm108938.htm, accessed Nov. 24, 2010.

2. “IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans,” Volume 60, World Health Organization - IARC, Aug. 26, 1997.

Published in WholeFoods Magazine, January 2011