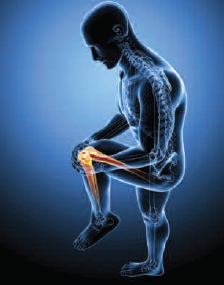

The mention of joint and inflammation support supplements might conjure up images of people with old, creaky joints, in need of some help retaining basic mobility and comfort. But in light of current trends, it should also bring to mind healthy, resilient joints, and active people young and old who are looking to stay mobile and pain free.

“This category has historically been led by consumers who are reacting to a health concern, but we’re seeing that trend shift, with more people incorporating these products into an everyday preventative regimen, especially among younger, active consumers,” says Angela McElwee, vice president of sales operations for Gaia Herbs, Brevard, NC.

As for how these supplements actually work, let’s not view joint supplements as simply as the Tin Man viewed his oil can, and inflammation care as just extinguishing a flame. Instead, let’s try for some more thorough explanations, as we take a look at some recent science on these subjects as well.

Also, we’ll examine how this whole category is affected by the negative U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) stance on “inflammation” as a supplement marketing tool. Following the way manufacturers are reacting and adapting to regulatory action is important to understanding this market.

“Inflammation” and Regulation

A substantial speed bump has been placed on the road to marketing joint and inflammation supplements. FDA has made it clear, through public statements and warning letters sent to companies, that the use of the word “inflammation” when describing a supplement’s benefits is not acceptable to the agency in many instances. This is because regulators consider inflammation a bodily process involved in various disease states.

As those who make and sell supplements know, saying a supplement treats or cures a disease doesn’t fly. As we’ll hear, FDA allows “inflammation” to be used in certain contexts, and most marketers believe the essential message can still be passed along to consumers, despite this regulatory obstacle.

FDA’s intentions in this area have become clearer recently, according to Trisha Sugarek MacDonald, B.S., M.S., director of R&D/national educator for Bluebonnet Nutrition Corp., Sugar Land, TX. One instance where the agency emphasized its stance against “inflammation” was during former FDA director of the division of dietary supplement programs Daniel Fabricant Ph.D.,’s presentation at SupplySide MarketPlace 2013, and it has been further reinforced in seminars and other dialogues with the industry. It has also been a topic within warning letters sent to supplement companies about the marketing of their products.

But, there are no official rules or even a guidance from FDA to address the concept specifically. So, the industry has had to sort out FDA’s parameters and draw conclusions from the agency’s actions. “The context of the claim and the substantiation of the claim matter. There are some non-disease states that result in pain and inflammation,” notes Paul Dijkstra, CEO of InterHealth Nutraceuticals, Benicia, CA.

Sugarek MacDonald echoes this interpretation, saying, “The bottom line is FDA will object to ‘Healthy Inflammation Response’ claims, unless the claim is specifically and expressly limited to a non-disease state.” What this means in practical terms is that saying a supplement supports “healthy inflammation response after vigorous exercise” or “running a marathon” should be acceptable, she says. In fact, those were examples specifically provided by FDA.

Rodney Benjamin, director of R&D and technical support at Bergstrom Nutrition, Vancouver, WA, says that this point of view from FDA is not new. Simply put, pain and inflammation generally stem from disease states like arthritis, and treating these conditions is considered to be the realm of drugs. “However, the FDA has given us the caveat that inflammation and/or pain due to exercise can be addressed by dietary supplements,” he says. FDA has been clear on what is acceptable, Benjamin feels, and the only recent change is an uptick in enforcement action.

Rodney Benjamin, director of R&D and technical support at Bergstrom Nutrition, Vancouver, WA, says that this point of view from FDA is not new. Simply put, pain and inflammation generally stem from disease states like arthritis, and treating these conditions is considered to be the realm of drugs. “However, the FDA has given us the caveat that inflammation and/or pain due to exercise can be addressed by dietary supplements,” he says. FDA has been clear on what is acceptable, Benjamin feels, and the only recent change is an uptick in enforcement action.

Is this development something the supplement industry can or should accept? Is it already in the process of accepting and adapting to it? Benjamin says that while the industry is grateful, FDA recognizes certain contexts where inflammation comes from a non-diseased state, like exercise. This still leaves open questions.

One is: “Why do dietary supplements only impact inflammation from exercise?” Benjamin wonders how FDA will ultimately respond if the industry continually pushes for a definitive answer to this question. Will regulators say, “You are correct. We should allow dietary supplements to say they support healthy inflammation, regardless of cause”? Or will they say, “You are correct. All inflammation, regardless of cause, can only be treated by drugs”?

The scope of the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) includes claims that dietary supplements support structure and function, points out Cheryl Myers, chief of scientific affairs and education for EuroPharma, Inc., Green Bay, WI. “The inflammatory response is clearly a healthy function in the body, just as an immune response might be,” she says. If supplements can be said to support immune health, she believes it is unclear why FDA thinks claims regarding inflammation are problematic. While it’s true, Myers says, that inflammation is often a result of disease or damage, phrases including the word “inflammation” don’t necessarily make reference to these conditions.

Gene Bruno, M.S., M.H.S., director of category  management for Twinlab, New York, NY, follows a similar line of thought. “Consider that inflammation is a natural component of our body’s immune response. Also consider that there are various situations in which inflammation is not part of a disease/

management for Twinlab, New York, NY, follows a similar line of thought. “Consider that inflammation is a natural component of our body’s immune response. Also consider that there are various situations in which inflammation is not part of a disease/

injury process,” he says. These situations include inflammation spurred by diet, such as eating excessive carbohydrates, or inflammation caused in some individuals by consuming casein or gluten. He also cites menopause, psychological stress, environmental toxins and cold temperatures as non-disease conditions that can lead to inflammation.

Speaking more generally, Scott Steinford, CEO of Doctor’s Best, San Clemente, CA, notes that chronic inflammation is usually closely associated with disease, but inflammation in and of itself is not. “Inflammation relief, as a claim, can just as easily be applied to acute inflammation as chronic inflammation,” Steinford says.

The FDA’s own Structure/Function Claims—Small Entity Compliance Guide, Criterion 5, according to Bruno, is meant to address cases where it is unclear whether a product is intended to diagnose, mitigate, treat, cure or prevent a disease. Qualifying it as his own personal interpretation, Bruno says that claims regarding inflammation may or may not be a disease claim based on context. If it is clear from the context of a claim that a supplement is being represented as a member of a class intended to affect structure/function, and not disease, then the claim should be permissible.

He acknowledges, however, that any unqualified dietary supplement claim regarding “joint inflammation” would likely violate existing regulations because it could be construed as linking the product with arthritis or another joint-related disease.

While Sugarek MacDonald says her company fully supports FDA and its guidelines, she explains that it is sometimes difficult to convey a supplement’s structure/function application without referring to the physiological mechanism involved. Added to this frustration is some genuine confusion over FDA’s stance, as Bruno says, again in his own opinion, that recent warning letters don’t seem to follow the letter of FDA’s own guidance documents. This inconsistency creates uncertainty over how to construct appropriate, non-disease-related inflammation claims.

While Sugarek MacDonald says her company fully supports FDA and its guidelines, she explains that it is sometimes difficult to convey a supplement’s structure/function application without referring to the physiological mechanism involved. Added to this frustration is some genuine confusion over FDA’s stance, as Bruno says, again in his own opinion, that recent warning letters don’t seem to follow the letter of FDA’s own guidance documents. This inconsistency creates uncertainty over how to construct appropriate, non-disease-related inflammation claims.

The issue is nonetheless becoming clearer, Dijkstra believes, but there is still a need for some official guidance. Those holding their breath may be disappointed, however, says Lou Paradise, president and chief of research of Topical BioMedics, Inc./Topricin, Rhinebeck, NY. He says it’s unlikely FDA will provide any concrete guidance, clarification or proposed rules on this issue.

Despite this, Benjamin thinks FDA has done a good job letting the industry know where it stands. “I would be surprised to see anything new from the agency except in the area of enforcement actions,” he says.

In navigating this issue, Benjamin says his company consulted its regulatory legal team, and designed studies to assess the efficacy of its ingredient in addressing pain specifically induced from acute exercise. The company did this because, as alluded to, exercise is an area where FDA has suggested it’s acceptable to make inflammation claims, provided adequate substantiation exists.

Chronic inflammation clearly underlies conditions like osteoarthritis, and an effective dietary ingredient should be able to relieve it in a way that leads to tangible benefits for consumers, says Joosang Park, Ph.D., vice president of scientific affairs at BioCell  Technology, LLC, Newport Beach, CA. He says that although FDA does not allow marketers to make direct anti-inflammatory claims, companies can still communicate benefits for joints to the consumer, via structure/function claims that are substantiated by research. Claims that are in regulatory compliance for his company’s collagen ingredient (BioCell Collagen), Park says, include “promote healthy joint and cartilage” and “promote joint comfort and mobility.” He adds, “It can be hypothesized that these benefits are not experienced without a significant reduction of inflammation in the joint.”

Technology, LLC, Newport Beach, CA. He says that although FDA does not allow marketers to make direct anti-inflammatory claims, companies can still communicate benefits for joints to the consumer, via structure/function claims that are substantiated by research. Claims that are in regulatory compliance for his company’s collagen ingredient (BioCell Collagen), Park says, include “promote healthy joint and cartilage” and “promote joint comfort and mobility.” He adds, “It can be hypothesized that these benefits are not experienced without a significant reduction of inflammation in the joint.”

In light of FDA’s recent emphasis on the topic, Sugarek MacDonald says her company approaches marketing cautiously, while still conveying the necessary messages to consumers. For example, terminology like the following may see use in labeling and marketing: “to support joint health or care,” “improve joint mobility and comfort levels” and “joint discomfort and function is improved with _____, according to studies.”

It would still seem that simply referencing support for a healthy inflammatory response does not involve a reference to disease or damage, Myers says. “However, we comply with all FDA regulations and adapt as needed. We follow reports of rule changes and interpretations carefully,” she says.

Several joint health claims are probably safe to make, Bruno explains, assuming that the substantiation is there. But, he says claims specifically referencing inflammation will remain a trickier area.

As frustrating as the situation is for legitimate companies in the supplement space that simply want to say more about their products, Paradise says the prudent tact is to stick to what is permitted. Accepted functional claims provide enough latitude in highlighting the benefits of supplements.

Regardless of how this conversation continues to play out, the natural products industry should be focused on educating consumers and retailers, as opposed to making claims that threaten to cross regulatory lines, Paradise feels. FDA, he believes, is more likely to pursue individual companies that lead with inflammation messaging for their products.

The good companies are often the ones already engaged in providing education, Paradise says. “However, unfortunately within the industry, there are a number of bad players making claims way beyond the scope of their products,” he explains, adding that these companies are drawing the attention of regulators and making it more difficult for honest companies to do business.

The good companies are often the ones already engaged in providing education, Paradise says. “However, unfortunately within the industry, there are a number of bad players making claims way beyond the scope of their products,” he explains, adding that these companies are drawing the attention of regulators and making it more difficult for honest companies to do business.

Consumers are the ultimate arbiters of all of this, argues Weiguo Zhang, president of Synutra Ingredients, Rockville, MD. For that reason, the intricacies of marketing are not really so big an issue. “Joint health is one of the product categories where consumers either experience results, or they don’t,” says Zhang.

Why Does My Knee Feel Better?

Behind the success of buzzworthy supplements like curcumin, glucosamine and chondroitin are physiological processes that aren’t easy to grasp. In fact, science is still unraveling just what goes on in many cases. A walk down the inflammatory pathway and a peek at recent science, including human trials, will help make things clearer.

Joint support, as a category, can be divided into two subcategories, believes Chris D. Meletis, N.D., director of science and research for Trace Minerals Research, Ogden, UT. The first is classical nutritional support for joints, which includes options like glucosamine, chondroitin, hyaluronic acid and MSM. The body puts this nutritional support toward dealing with daily wear and tear on joints.

Uncontrolled wear and tear may lead consumers to the second category, which involves inflammation and discomfort from dysfunctional, damaged joints. Typically, consumers seek to manage the latter through OTC anti-inflammatories, aspirin being the primary option in the non-supplement market, according to Meletis. “What is intriguing about this example is that we can trace its origins to chemists working at Bayer AG that synthetically transformed salicin from the botanical meadowsweet,” he says, adding many modern medications can trace their origins similarly.

One botanical still squarely in the supplement arena is curcumin, derived from turmeric. “The growth of turmeric as an ingredient in these categories has been tremendous, with ever-increasing numbers of consumers touting the benefits of this herb for a variety of reasons,” says McElwee. Turmeric (Curcuma longa) has been used historically throughout India, China  and Indonesia for both culinary spice and medicinal purposes, according to Tori Hudson, N.D., member of the Gaia Herbs scientific advisory board. The primary medicinal part of the plant is the rhizome, or root, and traditional applications have included bruises, sprains and joint inflammation.

and Indonesia for both culinary spice and medicinal purposes, according to Tori Hudson, N.D., member of the Gaia Herbs scientific advisory board. The primary medicinal part of the plant is the rhizome, or root, and traditional applications have included bruises, sprains and joint inflammation.

Curcumin, according to Jay Levy, director of sales at Wakunaga of America, Mission Viejo, CA, is one example of the nutrients and botanicals today’s supplement manufacturers are turning to for targeting inflammation and offering fast relief and improved range of motion. He says it is a highly pleiotropic molecule (meaning it produces various effects), with an excellent safety profile. Experimental models in humans and animals have shown anti-inflammatory properties of curcumin, Levy explains.

Found within turmeric are polyphenolic curcuminoids, a group that includes desmethoxycurcumin, bisdesmethoxycurcumin, cyclocurcumin and curcumin (diferuloylmethane), according to Hudson. Research into curcumin’s mechanisms of action is diverse, but one major focus is its ability to down-regulate the important nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) inflammatory pathway. “By down-regulating the expression of NF-kB, curcumin thus decreases the activation of multiple downstream inflammatory genes,” Hudson says.

Sugarek MacDonald says it also inhibits 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) activity, each involved in inflammation. “By blocking the production of certain prostaglandins (hormone-like substances) and leukotrienes, curcumin has been shown in human studies to induce an anti-inflammatory reaction in the body, thus supporting joint health and mobility,” she says.

In addition to its effects on NF-kB, Levy says curcumin also inhibits arachidonic acid metabolism and the production of inflammatory cytokines. “What’s more, the vanilloid component in curcumin blocks transient receptor potential vanilloid 1, a receptor that plays a role in the perception of pain,” he says.

“Due to these anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin, an increasing variety of inflammatory conditions are being studied and explored to better understand its full scope of use,” says Hudson.

“Due to these anti-inflammatory effects of curcumin, an increasing variety of inflammatory conditions are being studied and explored to better understand its full scope of use,” says Hudson.

In one study cited by Hudson, 45 subjects with active rheumatoid arthritis were given either a prescription anti-inflammatory drug, a branded curcumin ingredient (BCM-95 from Dolcas Biotech) or both. Each group improved, but the curcumin only group showed the greatest improvement in measures of pain and swelling (1). Myers adds more detail on this study, noting that curcumin was found to be safe as no adverse effects occurred. In the drug group, 14% of the patients withdrew from the study due to adverse effects, while no patients withdrew from the curcumin group.

Levy points to a similar study, a randomized clinical trial recently published in Clinical Interventions in Aging (2). Some 367 subjects with knee osteoarthritis were divided into two groups, one receiving 1,500 mg of curcumin daily and one receiving 1,200 mg of ibuprofen per day. Mean scores on a measure of osteoarthritic pain, stiffness and motion (WOMAC test) were improved in both groups after four weeks. Total scores, along with specific measures of pain and function, were similar for the curcumin and ibuprofen groups.

Hudson cautions that those on blood-thinning agents should tread carefully with curcumin, due to its ability to further inhibit platelet aggregration, and that curcumin use in these individuals should be discontinued two weeks before a surgery.

Summarizing curcumin’s benefits, Myers says, “Curcumin has been shown to modulate every pathway in the inflammatory system without wiping out any single pathway.” She says the lack of adverse effects from curcumin may be due to the fact that no single pathway, like COX-2, is impeded too much. Therefore, bodily systems reliant on those pathways are not damaged, as they can be with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Boswellia is another herb effective at modulating inflammation, according to Myers. It does not affect every pathway, but she says boswellia has been shown to make a major impact on the 5-LOX pathway. Due to this mechanism, it is thought to inhibit inflammatory leukotrienes. Myers gives an example of how manufacturers seek to synergize these botanicals. She says one combination product from her company utilizes curcumin, boswellia, nattokinase (to improve microcirculation) and the amino acid DLPA to help keep endorphins and enkephalins active for pain relief.

You’ve heard them referred to in tandem over and over, but just what are glucosamine and chondroitin? And why is glucosamine always said first? Chondroitin may need a better public relations firm, but its popularity with consumers is undeniable. It is a naturally occurring molecule that is a major component of cartilage. It absorbs fluid, mainly water, into the connective tissue, thus helping to keep cartilage healthy (3).

over, but just what are glucosamine and chondroitin? And why is glucosamine always said first? Chondroitin may need a better public relations firm, but its popularity with consumers is undeniable. It is a naturally occurring molecule that is a major component of cartilage. It absorbs fluid, mainly water, into the connective tissue, thus helping to keep cartilage healthy (3).

Zhang notes that commercial chondroitin comes from various sources, including bovine, porcine, avian or combinations of these. Chondroitin sulfate is not only a building block of cartilage, he says, but also slows the breakdown of cartilage. He says that his company makes various grades, or concentrations, of chondroitin available to supplement makers.

Chondroitin sulfate is bound to proteins like collagen and elastin in cartilage, tendons and ligaments. It can contribute to strength, flexibility and shock absorption in joints, explains Sugarek MacDonald. “Chondroitin and its effects are thought to lead to cartilage regeneration by providing the body with missing elements of cartilage,” she says.

Glucosamine, meanwhile, is produced naturally in the body, and plays a key role in building cartilage (4). No food sources of glucosamine exist. Most supplements are made from chitin, the hard outer shells of crustaceans, though glucosamine from other sources is available. Glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and other compounds are essential to cartilage formation, and whereas chondroitin is itself a GAG, glucosamine is a GAG precursor.

Glucosamine sulfate, beyond stimulating cartilage growth, also helps incorporate sulfur into cartilage, says Sugarek MacDonald. Sulfur is essential for joints, she says, as it stabilizes the connective tissue matrix of cartilage, tendons and ligaments. In supplements, glucosamine sulfate is usually combined with one of two mineral salts: sodium chloride (NaCl) or potassium chloride (KCl). According to Sugarek MacDonald, use of KCl is preferable today, since the American diet provides quite enough salt already, and not enough potassium.

To fully render their importance, Zhang says, “Joint health is consistently one of the largest selling product categories, with glucosamine and chondroitin combinations having led the pack for a number of years.” Both supplements can help with the rebuild and repair components of the joints, leading to improved mobility, explains Sugarek MacDonald.

Studies on glucosamine and chondroitin remain mixed, says Levy, and while they may help to rebuild cartilage, it can take weeks or months before consumers notice a difference.

A 2014 study described by Meletis demonstrated reduced joint space narrowing (JSN) through the use of glucosamine and chondroitin (5). Some 605 participants aged 45–75 received either glucosamine sulfate (1,500 mg), chondroitin sulfate (800 mg), both supplements or matching placebo capsules. JSN was measured over two years using digitized knee radiographs. A statistically significant reduction of JSN was found in the group that took both supplements, with a mean difference of 0.10 mm. Each group including placebo, however, saw the same amount of reduction in knee pain.

A 2014 study described by Meletis demonstrated reduced joint space narrowing (JSN) through the use of glucosamine and chondroitin (5). Some 605 participants aged 45–75 received either glucosamine sulfate (1,500 mg), chondroitin sulfate (800 mg), both supplements or matching placebo capsules. JSN was measured over two years using digitized knee radiographs. A statistically significant reduction of JSN was found in the group that took both supplements, with a mean difference of 0.10 mm. Each group including placebo, however, saw the same amount of reduction in knee pain.

Despite the popularity of glucosamine and chondroitin, Park says that this pairing may only provide a partial approach to joint health because they lack support for collagen. Cartilage and the synovial cavity, which together make up the joint, require both GAGs (like chondroitin and hyaluronic acid) and collagen to thrive. He says his company’s ingredient (BioCell Collagen) replenishes all of these molecules, as it provides hyaluronic acid, chondroitin sulfate and collagen type II. “Data also suggest that its mechanism of action may include stimulation of cartilage-forming chondrocytes to produce collagen type II, which is implicated for cartilage rebuilding,” Park says.

A study on this patented ingredient examined 80 subjects aged 40–70 (average age of 55) dealing with advanced joint discomfort (6). Park says it was demonstrated to be effective at reducing pain when compared with placebo, thereby enhancing daily physical activities.

Parris Kidd, Ph.D., chief science officer at Doctor’s Best, says that collagen types I and III are also commonly present in joints and elsewhere in the body’s tissues. In supplements, collagen can be pre-hydrolyzed to allow for more ready absorption.

Another collagen ingredient, according to Dijkstra, recently underwent a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (7). The subjects were healthy, exercising adults, and 40 mg of the ingredient (UC-II from InterHealth) was provided for 120 days. A physical stressor in the form of a standardized stepmill procedure was used, and subjects exercised until they felt discomfort. The trial found improved knee extension in subjects taking the supplement. They also exercised longer before experiencing joint discomfort compared to before the trial and recovered faster from joint discomfort after exercising. “The healthy subjects in this study represent the perfect population for dietary supplements,” Dijkstra says.

|

Joint and Inflammation Support Products The following products and ingredients are available from the companies interviewed in this feature.

Bergstrom Nutrition: OptiMSM. |

|

Omega-3 fatty acids, particularly DHA and EPA, have an established track record for reducing inflammation, which Levy says makes them a viable option for inflamed joints. Their anti-inflammatory effect delays the catabolic breakdown of cartilage, he says. Research shows this effect may be due to the inhibition of the COX enzyme, which produces prostaglandin hormones that induce inflammation. Research also shows that as basic components of cartilage and synovial fluid, omega-3s stimulate the anabolic process of cartilage metabolism (cartilage building), Levy explains.

Sugarek MacDonald adds that a proper ratio of omega-3s is important. She points to her company’s use of 750 mg of EPA and 134 mg of DHA in combination to support joint health. Kidd adds support for a specific source of omega-3s. “Authentic krill extract can provide very substantial support for joint health,” he says.

An unsung hero in this sector, says Levy, is aged garlic extract (AGE). “A powerful anti-inflammatory herb, AGE also is high in sulfur compounds which studies suggest is required to help crosslink collagen fibers that form the structure of cartilage,” he says. Compounds in garlic have been found to protect against osteoarthritis, he explains. Specifically, researchers have noted that the diallyl disulphide in garlic represses the expression of enzymes linked with the condition (8).

Another way AGE might benefit joints is through antioxidant activity. Levy says the reactive oxygen species that antioxidants combat have been shown to influence normal chondrocyte (cartilage cell) activity. Numerous clinical trials have shown AGE acts as a powerful anti-inflammatory agent in the context of the cardiovascular system. “No doubt, future studies will focus on this physiological action as it relates to inflammatory conditions that affect joints,” says Levy.

An extract of French maritime pine bark (Pycnogenol) is a natural NF-kB inhibitor, and can help control inflammation, swelling and oxidative stress, says Sébastien Bornet, director of global marketing at Horphag Research (worldwide exclusive supplier of Pycnogenol), Hoboken, NJ. In studies, this extract has been shown to promote joint mobility and flexibility and to naturally relieve aching.

Bornet says it can play a role in physical activity by improving endurance and recovery, protecting degenerating cartilage collagen by inhibiting MMP enzymes, and stimulating the production of hyaluronic acid and collagen. Several clinical trials document its ability to improve osteoarthritis and help joints recover (9). Pycnogenol selectively binds to collagen and elastin, and aids in the production of endothelial nitric oxide, helping to improve blood flow.

All these actions stand in contrast, Bornet explains, to the way painkillers work. “With painkillers, a patient may expect relief within 30–60 minutes, but the medication does nothing to improve the joints, and may have harsh side effects,” he says.

Tim Hammond, vice president of sales and marketing at Bergstrom Nutrition, explains that MSM helps fight exercise-induced inflammation by cutting down on the amount of free radicals formed by the intense activity. One recent study found it decreased measures of muscle damage and soreness (10). “This means less recovery time and a quicker return to exercise or daily activity. Current research continues to investigate the effects of MSM supplementation on oxidative stress, inflammation, and functional and athletic measures of performance,” Hammond says.

According to research provided by Meletis, minerals like boron, zinc, copper and selenium are protective of healthy joints. A mineral supplement was found to improve WOMAC scores over baseline after 24 weeks (11). Individual measures of pain, stiffness and physical activity each improved significantly over placebo.

Another natural option for inhibiting COX 1 and 2 enzymes is cherries. According to Sugarek MacDonald, cherries have also been shown to lower blood levels of uric acid. A high level of uric acid is associated with gout pain, she says, and researchers think that compounds in cherries inhibit the relevant inflammatory pathway. She goes on to list other options for promoting healthy joints, including bovine cartilage, sea cucumber, vitamin C, vitamin B6 and pineapple bromelain.

“The joints are living tissue just like everything else in the body, and all our tissues require all the vitamins and essential minerals,” says Kidd. In summarizing the options consumers have for joint support, he recommends multiple vitamin-mineral supplements that provide nutrients in their active forms as a good choice for everyone.

In addition to dietary supplements, Paradise emphasizes the impact that topical products can have in this category. He says his company’s patented healing cream technology (Topricin) was developed by looking at the metabolic and cellular causes of pain. This includes how excess inflammatory fluids and toxins undermine joint health, as well as how underlying deficiencies lead to joint deterioration.

Active Lifestyles and Joint Health Marketing

Broadly speaking, the joint and inflammation category is still largely geared toward older people experiencing issues (Baby Boomers are today’s prime candidates). But interest in prevention and maintenance among younger consumers is a definite trend.

“Joint health is an increasingly popular issue among active Baby Boomers and 30 to 40 year olds alike,” says Dijkstra. As such, supplements traditionally designed to help with athletic performance are now helping with repair and recovery. “Joint health is important in many sports, including cycling, running, climbing, etc. There is a trend to include joint-health ingredients in sports nutrition products,” he says.

The aging demographic has always been targeted in this category, and for good reason, says Meletis. “However, we focus on the weekend warrior athletes and those who used to be high school/college athletes who pushed their bodies to the limit and need support to continue an active lifestyle,” he says.

According to Paradise, most people don’t realize inflammation is vital to protecting the body, and that it is excess inflammation and toxins that cause problems. Many consumers, however, are catching on. “Younger people are starting to practice more preventive methods of health and wellness, not wanting to potentially end up with the disabilities and/or diminished quality of life that their parents or their grandparents have experienced,” Paradise says.

Hammond thinks joint health products should be considered as part of an overall prevention- and recovery-focused supplement protocol. “For example, Crossfit athletes are one group that could benefit from MSM supplementation, as they challenge different sets of muscles with exercises that continually change and are not just a series of repetitive motions,” he says.

Younger consumers bring their own set of expectations, according to McElwee. She says her company’s turmeric line has drawn in new, engaged, educated consumers who are asking questions about everything from sourcing to solvents. They are demanding transparency, and specifically to this category, they are interested in the extraction methods used to get curcumin from turmeric, and the bioavailability of the ingredient.

In Levy’s experience, the under-40 set has yet to take off as joint health product consumers. But Gen-Xers do seem to be looking for ways to protect their joints. He also points out that those currently middle-aged and older are more active than previous generations, as many participate in sports or work out regularly. These consumers want to look and feel younger, live longer and prevent disease. Healthy joints are a necessity for maintaining their active lifestyles, and many are turning to natural solutions for prevention. “As younger generations age, this desire may only strengthen. This bodes well for manufacturers of joint supplements,” Levy says.

Bornet explains that the millennial generation is driving growth in the supplement market as a whole, and in the joint health space, younger people are looking at scientific evidence with a focus on projecting their joints. “The aging population, specifically Baby Boomers, also remain an important factor in the market, and our data show that they are looking for natural alternatives to help them reduce the use of NSAID pain relievers,” says Bornet.

Steinford makes a similar observation, saying, “Some tout the benefits of NSAIDs as an answer to the problem of acute and chronic inflammation, but that is not an acceptable solution to many individuals, who will continue to seek alternatives through diet and supplements.”

There are other groups that joint health supplements can cater to strongly, Bornet adds, including overweight people and those with jobs that stress the joints. Those with sedentary lifestyles are at risk for joint health issues as well, he says.

Wellington Quan, general manager of the American market division of Prince of Peace Enterprises, Hayward, CA, feels it’s important to consider these lifestyle factors with regard to joint health. Staying active with daily exercise, he says, is an important contributor to the wellness of joints. “It is important for folks to keep a balanced approach between diet, supplementation, daily exercise and sleep,” says Quan. Proper stretching prior to exercise helps warm up joints and can reduce injuries. He also says that using topical productscan help with both pre-exercise warm up and post-exercise muscle recovery. His company’s topical joint health product, which comes in ointments, patches, creams and oils, is one example.

The category will be dominated by branded ingredients in the coming years, Dijkstra believes. “Joint health also continues to be an important category for consumers who are looking for new ingredients that are more effective than existing products,” he says, citing recent joint health coverage on outlets like The Dr. Oz Show.

For retailers looking to leverage all of this diverse interest in maintaining healthy joints and combating inflammation, Sugarek MacDonald offers some tips. First, avoid too much product redundancy. “Focus on one particular joint health subcategory or pick three popular items across the joint wellness categories for an overall joint care approach, and then rotate on a monthly basis,” she says. An endcap with glucosamine, turmeric and omega-3s, would be one example. Also include books on fitness, especially yoga and swimming, and provide literature that details the joint wellness benefits of each approach. She also says to not forget about very young customers in this category. Stores can provide literature or host kid-friendly educational seminars for parents and their children about joint health and being active. WF

References

1. B. Chandran, A. Goel, “A Randomized, Pilot Study to Assess the Efficacy and Safety of Curcumin in Patients with Active Rheumatoid Arthritis,” Phytother. Res. 26(11), 1719-25 (2012).

2. V. Kuptniratsaikul, et al., Efficacy and Safety of Curcuma domestica Extracts Compared with Ibuprofen in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Multicenter Study,” Clin. Interv. Aging. 20(9), 451-8 (2014).

3. “Chondroitin,” University of Maryland Medical Center, last updated May 7, 2013, https://umm.edu/health/medical/altmed/supplement/chondroitin, accessed May 1, 2014.

4. “Glucosamine,” University of Maryland Medical Center, last updated May 7, 2013, https://umm.edu/health/medical/altmed/supplement/glucosamine, accessed May 1, 2014.

5. M. Fransen, et al., “Glucosamine and Chondroitin for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Double-blind Randomised Placebo-controlled Clinical Trial Evaluating Single and Combination Regimens,” Ann. Rheum. Dis. [Epub ahead of print].

6. A.G. Schauss, et al. “Effect of the Novel Low Molecular Weight Hydrolyzed Chicken Sternal Cartilage Extract, BioCell Collagen, on Improving Osteoarthritis-related Symptoms: A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Trial,” J. Agric. Food. Chem. 60(16), 4096-101 (2012).

7. J.P. Lugo, et al., “Undenatured type II collagen (UC-II) for joint support: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in healthy volunteers,” J. Int. Soc. Sports. Nutr. 10(1), 48 (2013).

8. F.M. Williams, “Dietary garlic and hip osteoarthritis: evidence of a protective effect and putative mechanism of action,” BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 11, 280 (2010).

9. “New Study: Pycnogenol Naturally Reduces Knee Osteoarthritis,” Mar. 9, 2008, http://www.pycnogenol.com/home/detail/new-study-pycnogenol%c2%ae-naturally-reduces-knee-osteoarthritis/?,=, accessed May 1, 2014.

10. D. Kalman, “A Randomized Double Blind Placebo Controlled Evaluation of MSM for Exercise Induced Discomfort/Pain,” FASEB J. 27, 1076.7 (2013).

11. H. Bansal, et al., “ConcenTrace (CTMD) Clinical Trial,” Trace Minerals Research (2012).

Published in WholeFoods Magazine, June 2014