If you are focusing on the wrong thing, then you can’t focus on the right thing. If you were falsely told your entire life to focus on something, then you have been misled and your health may suffer. The “Great American Diet Experiment” may be nearing its final stage, now that the facts are finally allowed to reach all scientists and the public. As discussed later in this column, at least some American scientific journals are now allowing the full facts to be published rather than having the “reviewers” insist that certain true—but embarrassing to the Heart–Diet establishment—data be removed. Yes, the suppression of scientific facts that contradict or question the dogma of the controlling establishment still occurs.

The “Great American Diet Experiment” has been responsible for many thousands of premature deaths from heart disease by vilifying many natural foods and thereby greatly increasing the intake of harmful synthetic (man-made) trans-fats, sugars and artificial sweeteners in a zealous effort to reduce the natural dietary fats that are neutral to heart disease. In the United States, official doctrines and dogma dissuaded us from eating many of the natural foods that have made humans healthy for thousands of years and encouraged us to eat fractured foods consisting of synthetic chemicals never before ingested by mankind. The rest of the world refused to be guinea pigs and mostly ignored this experiment.

Vested interests spent trillions of our tax dollars and donations trying to  convince us to do so. Experts and officials, including physicians and dieticians, as well as officials from U.S. government agencies and disease foundations (not-for-profit organizations, but wherein the officials receive huge salaries) have paraded before us for decades to get us to switch to new processed foods. Fractured-food advertisers spent billions of dollars selling us so-called heart-healthy, low-fat foods. The “food police” publically campaigned to force food providers to switch their cooking methods to those that increased trans fats (and today they are campaigning to remove these same trans fats with no mention that it was their efforts that caused the increase in trans fats in the first place). These efforts have been successful, as nearly everyone “knows” that saturated fats cause heart disease. After all, we have been told that for decades by trusted leaders of nearly every government health agency and disease organization. Another common misconception is that animal fats are saturated fats and that plant fats are unsaturated fats. As we will discuss later, natural whole foods are mixtures of both saturated and unsaturated fats. Some plant fats can be predominantly saturated fats and some animal fats can be mostly unsaturated fats.

convince us to do so. Experts and officials, including physicians and dieticians, as well as officials from U.S. government agencies and disease foundations (not-for-profit organizations, but wherein the officials receive huge salaries) have paraded before us for decades to get us to switch to new processed foods. Fractured-food advertisers spent billions of dollars selling us so-called heart-healthy, low-fat foods. The “food police” publically campaigned to force food providers to switch their cooking methods to those that increased trans fats (and today they are campaigning to remove these same trans fats with no mention that it was their efforts that caused the increase in trans fats in the first place). These efforts have been successful, as nearly everyone “knows” that saturated fats cause heart disease. After all, we have been told that for decades by trusted leaders of nearly every government health agency and disease organization. Another common misconception is that animal fats are saturated fats and that plant fats are unsaturated fats. As we will discuss later, natural whole foods are mixtures of both saturated and unsaturated fats. Some plant fats can be predominantly saturated fats and some animal fats can be mostly unsaturated fats.

The now-disproven theory was so easy to believe because it was so “logical.” The trouble is that it wasn’t true 50 years ago and it’s not true now. Our bodies don’t run on common “logic,” but on complex biochemical reactions. One does not become muscular merely by eating animal muscle. And, one can become fat by overeating any food group—protein, carbohydrate or fat. The concern is that excess carbohydrate intake—especially fructose, which has become so prevalent—can also lead to diabetes. The simple carbohydrate fructose is converted into glycerol, the backbone of triglycerides. Triglycerides are considered a risk factor for heart disease. Fructose has also been shown to evade the normal appetite-signaling system, involving insulin, leptin and other regulating hormones. This is due to fructose being metabolized primarily in the liver whereas glucose-based carbohydrates are metabolized primarily within the gastrointestinal tract.

Even Time magazine reviewed the demise of the dietary fat theory in its June 23 issue as an in-depth cover story, “Ending the War on Fat.” I wholeheartedly recommend this article.

Even Time magazine reviewed the demise of the dietary fat theory in its June 23 issue as an in-depth cover story, “Ending the War on Fat.” I wholeheartedly recommend this article.

In March, we chatted with Aseem Malhotra, M.D., about his editorial in the British Medical Journal, “Saturated Fat Is Not the Major Issue”. After shooting down the widely popular, but incorrect, beliefs about dietary fat with solid scientific evidence, Dr. Malhotra pointed out that common fractured foods and sugars used to replace saturated fats are indeed major factors in heart disease. In his call for action, Dr. Malhotra stated, “The dogma of low-fat diet is damaging public health and contributing to the obesity epidemic, and this has to stop.”

The public has been misled for decades. They have been encouraged to eat food substitutes containing new ingredients to the human diet in the form of synthetic trans-fats and refined carbohydrates. What can be done to correct this misinformation? Let’s start with education and scientific facts. This month, I’ve called upon an outstanding lipid (fat) expert Gerald McNeill, Ph.D., to give us the real scientific facts about dietary fats and health. Here are many things you wanted to know about fats and health, but didn’t know who to ask. Many of you will find several surprises.

Passwater: I can’t resist the old joke I use when chatting with lipid researchers: Why did you become a fat chemist?

McNeill: Growing up in a working-class neighborhood in Ireland 40 years ago, I was strongly influenced by the conservative Irish Catholic Church, in which I was very active. After high school I longed for a more quantitative and logical model for “Life the Universe and Everything.” This led me to university and a Ph.D. in biochemistry at the Irish Dairy Research Centre on casein structure in milk. While there, I transferred to the butter department and that began my career in fats and oils.

Later, I worked in various research institutions developing “clean” processes for fats and oil modification using natural catalysts (lipase enzymes): low temperature, no chemicals. At Unilever Research UK, I lead a four-year discovery project for the development of healthy lipids for a new supplement subsidiary called, Lipid Nutrition. That provided me with the tools to find my way around nutrition studies.

Unilever assigned me to the United States to  build up a new R&D group at a fats and oils factory outside Chicago for Loders Croklaan. In 2005, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that trans fat would be labeled on retail packaged goods, I determined (1) that palm oil was by far the best functional alternative to trans fat, and (2) reviewed the nutritional issues around trans fat and saturated fat. I concluded that saturated fat was not associated with risk of heart disease, but trans fat was highly atherogenic.

build up a new R&D group at a fats and oils factory outside Chicago for Loders Croklaan. In 2005, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced that trans fat would be labeled on retail packaged goods, I determined (1) that palm oil was by far the best functional alternative to trans fat, and (2) reviewed the nutritional issues around trans fat and saturated fat. I concluded that saturated fat was not associated with risk of heart disease, but trans fat was highly atherogenic.

On that basis, we immediately began to eliminate all our partially hydrogenated products and replace them with naturally semi-solid palm oil and non-hydrogenated vegetable oils. It is very gratifying that our company has been influential in “making a lot of people a little bit healthier.”

So while I had always considered the humble triglyceride molecule (major form of stored fat) to be very simple and boring, nothing could be farther from the truth.

Passwater: Heart disease is a major problem, but unfortunately the public has been fed the wrong advice for about a half-century about diet and heart disease. They have been told to avoid certain foods that are actually heart-healthy and told to eat many foods that are heart unhealthy. For example, the public has been “brain-washed” into believing that saturated fats cause heart disease and that all fats are undesirable. As a result they are often urged to eat many foods in which fat has been replaced with sugar. Time magazine has an interactive display showing how the American diet has changed over the years from 1970 to now (3). As Americans lowered their fat intake, they had to be replaced with something else. What? Sugar? It reminds me of the quote attributed to George Bernard Shaw: “No diet will remove all the fat from your body because the brain is entirely fat. Without a brain, you might look good, but all you could do is run for public office.”

Let’s start with a look at saturated fats. Do saturated fats increase the risk of heart disease?

McNeill: Saturated fat does not increase risk of heart disease! In the early days of the rapid increase in incidence of heart disease, scientists were under intense pressure to come up with a simple and effective cure. The rise in incidence of heart disease coincides closely with the virtual elimination of death from infectious diseases, due to good hygiene practices and the invention of antibiotics. The resulting dramatic increase in life expectancy of the U.S. population exposed a large number of people to diseases of aging for the first time, resulting in the new number one killer today: heart disease.

A true statement is, “Aging is the number one cause of heart disease.” Unfortunately, nobody knows how to reverse the aging process.

In the 1960s and 70s, researchers began to promote dietary fat as the main cause of heart disease. Fat and cholesterol can be seen in atherosclerotic lesions in humans. Animal models were fed cholesterol and quickly developed extensive blockages, especially in the rabbit. A very simplistic model called the “blocked pipe” was proposed. In this theory, when humans ate fat and cholesterol, the fat, and especially the saturated fat and cholesterol that was semi-solid, got into the bloodstream and got stuck in the bends of the arteries, just like the pipe under your kitchen sink. The simple solution was to cut down on fat consumption, especially saturated fat.

In the 1960s and 70s, researchers began to promote dietary fat as the main cause of heart disease. Fat and cholesterol can be seen in atherosclerotic lesions in humans. Animal models were fed cholesterol and quickly developed extensive blockages, especially in the rabbit. A very simplistic model called the “blocked pipe” was proposed. In this theory, when humans ate fat and cholesterol, the fat, and especially the saturated fat and cholesterol that was semi-solid, got into the bloodstream and got stuck in the bends of the arteries, just like the pipe under your kitchen sink. The simple solution was to cut down on fat consumption, especially saturated fat.

Major flaws in the hypothesis are immediately evident:

Fats are, by definition, semi-solid at room temperature due to a high content of saturated fat, and about 66% of our saturated fat intake is from meat, dairy and eggs. However, animals, including humans are warm blooded, and animal fats are all liquid at human body temperature—just the same as liquid vegetable oils. Any fat that is solid at body temperature (for example fully hydrogenated vegetable oil) cannot be digested and is excreted. Unlike rabbits, increasing cholesterol consumption does not increase the cholesterol content in blood serum of humans and does not appear to have any effect on risk of heart disease.

A second flaw is the fact that after digestion, fat does not enter the bloodstream and does not travel through the heart. Instead, it is transported via the lymph system directly to the tissues for use as energy or for long-term storage. Common sense dictates that the blocked pipe principle is incorrect, but the idea is still preserved to this day.

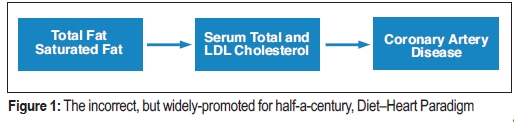

However, fats eventually do make their way from the liver into the bloodstream and through the arteries. There are two sources of fat in the body: (1) Dietary fat stored in adipose tissue and (2) fat that our own bodies synthesize from excess consumption of dietary sugar. All fats and oils are derived directly from sugar that is made by the fixation of CO2 and H20 during plant photosynthesis. Fat is processed in the liver and emulsified with a protein coat to prevent it from coalescing. With the advent of a large, well-controlled observational study called the Framingham Heart Study, researchers discovered that a high concentration of a blood serum fat particle called low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL cholesterol) was associated with increased risk of heart disease. Cholesterol is insoluble in water-based blood and is transported in blood in a lipoprotein as a carrier. Consumption of dietary saturated fat results in an increase in serum LDL cholesterol. Professor Ancel Keys, a prominent scientist at that time, coined the terms, “Diet–Heart Paradigm” and “Diet–Heart Hypothesis,” to describe the effect and this simple idea that saturated fat increases serum LDL and therefore increases risk of heart disease (see Figure 1). This concept is still in force today by mainstream policymakers and has not changed for the last 30 years, in spite of a huge body of research to the contrary.

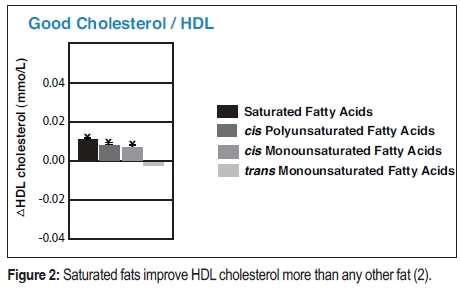

As more data from the Framingham Heart Study and other observational studies began to emerge, another fat particle was discovered called, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL cholesterol) (1). A high serum concentration of serum HDL particles was found to have the opposite effect of LDL; it is associated with a reduced risk of heart disease. It turns out that saturated fat also increases HDL cholesterol (see Figure 2)—more than any other fatty acid!

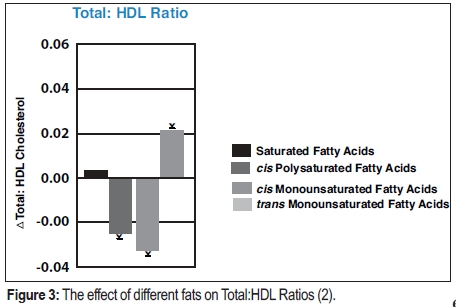

Researchers from the Framingham Study further discovered that the ratio of LDL:HDL (or Total Cholesterol:HDL Cholesterol) is the best blood marker for risk of heart disease. It effectively subtracts the positive effect of HDL cholesterol from the negative effect LDL cholesterol. Saturated fat consumption raises both LDL and HDL cholesterol by the about same relative amount and the LDL:HDL ratio does not change (see Figure 3). This predicts that saturated fat should have no effect on heart disease risk.

To the surprise of many, it shows that saturated fat neither increases nor decreases the Total:HDL Ratio. No change in Total:HDL Ratio predicts that saturated fat is not expected to increase or decrease risk of heart disease; it is neutral. Trans fat is the only fat that increases Total:HDL Ratio and increases risk of heart disease.

Unfortunately, many nutrition scientists and  journals today continue to ignore the HDL raising effect of saturated fat, making saturated fat look worse than it really is. Browsing through relevant publications in the field, the LDL-raising effect of saturated fat is highlighted prominently in the abstract, but HDL raising is rarely mentioned and only the highly motivated scientist spends the time to dig it out of large tables of results buried within the publication.

journals today continue to ignore the HDL raising effect of saturated fat, making saturated fat look worse than it really is. Browsing through relevant publications in the field, the LDL-raising effect of saturated fat is highlighted prominently in the abstract, but HDL raising is rarely mentioned and only the highly motivated scientist spends the time to dig it out of large tables of results buried within the publication.

However, trans fat also raises LDL cholesterol but does not increase HDL cholesterol; instead, it lowers it (see Figure 3). The Total:HDL Ratio indicates that trans fat is seven times worse than saturated fat. The neglect of the HDL cholesterol-lowering effect of trans fat has led to widespread use of partially hydrogenated oil (PHO) as a substitute for saturated fat, significantly increasing the incidence of heart disease, instead of lowering it, for more than 30 years.

Passwater: When did the message promoted to the public begin to back off of the saturated fat propaganda?

McNeill: While the combined effects of saturated fat and trans fat on LDL and HDL were ignored for over 30 years, the Diet–Heart Hypothesis was not proof of effect, and whatever way it was used, was not a direct proof of effect.

Scientists at the Harvard School of Medicine initiated a large observational study called the “Nurses’ Health Study” (4) to better determine cause and effect of fatty acids with actual heart disease and death from heart disease.

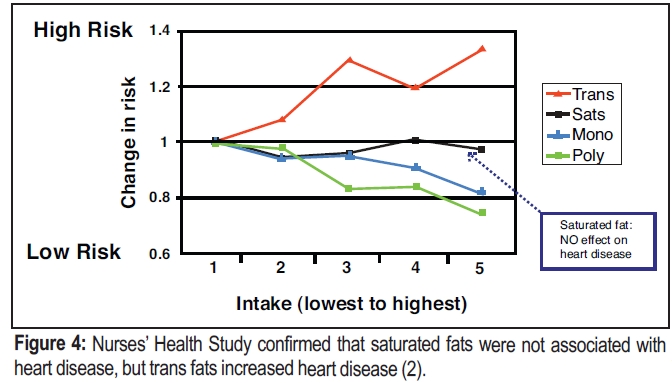

In 2005, after tracking the food intake of 80,000 nurses for 20 years, the study revealed that dietary saturated fat was not associated with heart disease (cardiovascular disease and coronary heart disease) at any intake level (highest intake = 11en%) (see Figure 4). Trans fat was positively associated with increased heart disease at just 2.5en%. Polyunsaturated fat was found to significantly reduce heart disease, and monounsaturated fat had a small positive effect.

The results of the Nurses’ Health Study confirmed the prediction of Total:HDL ratio for saturated fat; no effect on heart disease. However, policymakers totally ignored the results of both the Total:HDL ratio, and the landmark Nurses’ Health Study results.

Since the Nurses’ Health Study was completed, many other related observational studies have been published and combined together in large meta-analyses. A meta-analysis is a group of several related observational studies that are combined together to make a single large study. Combining different studies together generates much more reliable results and conclusions than any single study alone. In 2012, a meta-analysis coauthored by Professor Ron Krauss, M.D., former president of the American Heart Association (AHA) Nutrition Committee (5), revealed that saturated fat had no effect on the incidence of heart disease. The study concluded, “there is no significant evidence for concluding that saturated fat is associated with an increased risk of CHD or CVD.”

Since then, the biggest meta-analysis in this field was published by Cambridge University in 2013, with a combined total of more than 650,000 subjects. This study also found no effect of saturated fat on risk of heart disease (6).

Since then, the biggest meta-analysis in this field was published by Cambridge University in 2013, with a combined total of more than 650,000 subjects. This study also found no effect of saturated fat on risk of heart disease (6).

In spite of all the converging data from different approaches showing saturated fat is not harmful, policymakers like the AHA and the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee instead are calling for even lower saturated fat intake levels, as low as 6en% or less. To achieve such a low level of intake, about 60% of all dairy, meat and egg products would have to be eliminated from the American diet!

Passwater: We are now seeing some “official” recognition that trans fats are the dietary culprits in heart disease. Although we have been discussing trans fats in this column since 1993, there are always new readers. Please explain to them what are trans fats.

McNeill: Fatty acids are the main components of dietary fat. They are comprised of chains of carbon atoms with hydrogen and with an acid group at the end. When all the carbons are linked together with single bonds, they are called “saturated.” If the fatty acid chain contains one or more double bond, it is called “unsaturated”. There are two types of double bond: the natural “cis” bond that puts a kink in the molecule, or the artificial “trans” bond that is straight. The natural cis bond is usually liquid at room temperature, but trans bonds are higher melting and semi-solid at room temperature.

A commercial process called partial hydrogenation was widely introduced into the United States in the 1970s. This process takes natural polyunsaturated oil and heats it with a nickel-sulfur catalyst in the presence of hydrogen gas at high temperature and pressure. The natural cis bonds are partly converted into synthetic trans bonds. The natural oil is therefore converted into a semi-solid texture and is an alternative to animal fats and butter. By adjusting the reaction conditions, many different textures can be made, making versatile ingredients for the bakery and snack foods industries.

Passwater: Very few trans fats are produced in nature. Do man-made trans fats differ from natural trans fats?

McNeill: Natural trans fat is found in ruminant meat and milk fat. The rumen of the cow contains a complex mixture of bacteria and single-celled organisms that primarily breakdown the cellulose in grass. A byproduct of these organisms is a biological form of hydrogenation that generates vaccenic acid, a variant of trans fat. Synthetic trans fat has another variant called elaidic acid. Preliminary data (7) indicates that the natural trans fat is not as bad as synthetic trans fat, but is still worse than saturated fat.

Passwater: Why are man-made trans fats harmful to health?

McNeill: The main negative effect of man-made trans fat is related to heart disease risk. Because trans fat both increases LDL cholesterol and decreases HDL cholesterol, it is seven times worse than saturated fat. The first researchers to thoroughly investigate this effect were Dutch—not American—based in Maastricht University (2). Observational studies, such as the Nurses’ Health Study found direct evidence that even low levels of dietary trans fat (ca. 2.5en%) significantly increase the incidence of heart disease and death from heart disease. Subsequent observational studies and meta-analyses—the most recent and largest meta-analysis so far, with 650,000 participants (6)—all confirm that trans fat consumption is the main dietary risk factor for heart disease (coronary artery disease and cardiovascular disease).

A small body of research suggests that trans fat has other negative health effects, including promoting obesity and increasing markers of inflammation. However, we should not fall into the “good” versus “bad” trap, as if inanimate molecules could possess human characteristics.

Passwater: How can trans fats be reduced in the American food supply?

McNeill: In the American food supply, two main categories of fats and oils are needed to supply most of the needs of food processing and production. Liquid oils, used for frying or dressings, and a solid fat for baked goods and snack foods.

Frying. In the past, polyunsaturated oils like soybean oil and cottonseed oil were partially hydrogenated to extend shelf life in frying applications. Polyunsaturated fat is highly reactive to oxygen at high temperatures as found in fryers, and partial hydrogenation reduces polyunsaturated fat content, extending the shelf life.

Non-hydrogenated soybean oil has been used recently in many restaurants, but a polymer “goop” accumulates in the bottom of fryers. Some low levels of well-known toxic aldehydes form in the oil and find their way into finished foods and should be avoided.

New varieties of very stable high-oleic genetically modified (GM) vegetable oils including canola and soy are beginning to replace the polyunsaturated oils. They are highly stable and do not form polymers or toxic aldehydes.

New varieties of very stable high-oleic genetically modified (GM) vegetable oils including canola and soy are beginning to replace the polyunsaturated oils. They are highly stable and do not form polymers or toxic aldehydes.

A stable liquid form of palm oil is also available for frying, but has not been widely adopted due to the continued negativity toward saturated fat (contains approximately 42%). Note that there are no GM varieties of palm today, and due to the extreme complexity of the agronomics of palm farming, GM is not likely to be an option for many decades.

Baked goods and snack foods. The second category, baked goods and snack foods, requires a semi-solid fat for functionality. Historically, this category of foods was invented using animal fats, which are semi-solid at room temperature. Animal fats were effectively replaced by PHO 30 years ago, and are not an option for most food manufacturers today.

Natural palm oil (no chemical processes are used in the production of palm oil) is semi-solid with a balance of 50% saturated and 50% unsaturated fat. It is amazingly versatile due to a physical separation process called fractionation. The oil is melted and cooled slowly until fat crystals appear. The slurry is put into an expeller press where the liquid palm oil is pushed though. The solid crystals are retained and they form a hard waxy solid. This process is repeated several times to generate a wide range of highly functional products without the need for any chemical processing. IOI Loders Croklaan has more than 150 products available for the food industry today as healthy replacements for trans fat.

Passwater: Natural foods are not simply one type of fat or another. They are mixtures of fats. It is a common misconception that animal foods contain saturated fats while plant foods contain unsaturated fats. For example, beef fat is 54% unsaturated, lard is 60% unsaturated and chicken fat is about 70% unsaturated. Coconut oil, from the fruit of the coconut plant, is 85% saturated fat. Have some foods received an unwarranted bad reputation because of the misplaced fear of saturated fats?

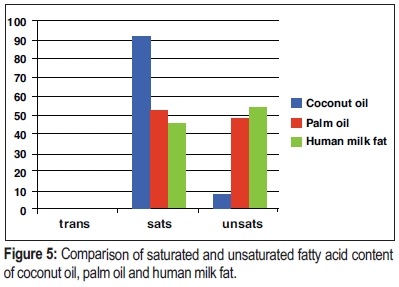

McNeill: Natural fats and oils are always a mixture of saturated and unsaturated fats (see Figure 5). As a general rule, living things strive to have the highest content of saturated fat in their bodies, while maintaining the fat in a liquid state. Saturated fat has the highest energy content per gram, making it the most energy-dense storage medium in their bodies. The fat cannot become solid, because solid fat cannot be metabolized and is useless.

Warm-blooded animals have a high level of saturated fat at about 50%. Plants that grow near the equator, like the palm fruit tree and others, also have about 50% saturated fat in their oil and the ambient temperature at the equator (about 35 degrees Celsius) is similar to the body temperature of animals. Plants that grow in cool climates, like soybeans and canola, have between 10–25% saturated fat depending on the growing region.

In the United States, the cutoff point that defines a “saturated fat” is about 30%, just higher than the saturated fat content of cottonseed oil—the commercial domestic oil that has the highest saturated fat content!

When considering the effect of mixtures of saturated fat and unsaturated fat, the unsaturated fat will lower LDL cholesterol and the saturated fat will increase the HDL cholesterol in the mixture. Natural blends of fats can therefore never promote heart disease risk, and can even be beneficial due to the inherent neutral effect of the saturated fats.

Passwater: So for many decades, the official agencies and non-profits have not only been focusing on the wrong factors, but they also have been discouraging the consumption of healthy foods that are protective. This has caused an untold number of premature deaths. Is there evidence that the official dogma is changing?

McNeill: Clearly, the “official” policymakers have completely ignored every piece of published research that did not conform to the original saturated fat “Diet-Heart Hypothesis” of the 1950s—and that has not changed today. The result of that “hypothesis” was the substitution of saturated fat with trans fat; almost no human studies had been ever been carried out on trans fat at the time. About 25 years later, Dutch researchers (2) found that saturated fat significantly increases HDL and trans fat lowers HDL. Saturated fat studies published in the United States never mentioned the HDL-raising effect in the abstract or summary. I contacted a couple of researchers as to why this was the case—the answer was, “I had the HDL data in the abstract, but the reviewer said it had to be taken out or the paper would not be published.”

The outcome of wrongly “demonizing” saturated fat was the introduction of a huge amount of synthetic trans fat into the diet that resulted in increased heart disease for decades.

But in spite of the disastrous inaction of some policymakers, many serious scientists recognize the mistakes of the past, and a growing movement agrees, “saturated fat may not be as bad as we once believed.”

Passwater: I also have had been told by researchers that their data had to be removed to gain publication. Time magazine reports that even leading nutritionists with facts that contradicts the current dogma have been refused publication by U.S. journals and they have had to resort to foreign journals to have their data published. The Time article referenced earlier in this column stated, “But the anti-fat message went mainstream and by the 1980s, it was so embedded in modern medicine and nutrition that it became nearly impossible to challenge the consensus. Dr. Walter Willet, now the head of the department of nutrition at the Harvard School of Public Health, tells me that in the mid-1990s, he was sitting on a piece of contrary evidence that none of the leading American science journals would publish.”

Dr. Fred Kummerow, who was the first to report scientific studies showing that trans fats were harmful and that cholesterol and saturated fat were not linked to heart disease, immediately lost his funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). We will chat with Dr. Kummerow about how it took private funding to continue his research in an upcoming interview. Similarly, Dr. Mary Enig could not get her trans fat studies published. Instead she was harassed, but she was tenacious. Can the public play a role in this by using their pocketbooks to buy only the foods low in trans fats?

McNeill: The situation with trans fat in food products today is greatly improved since the FDA mandated that trans fat should be included in the Nutritional Facts Panel of retail food products, effective January 1, 2006. According to the FDA, this has resulted in a 75% reduction in trans fat in the U.S. food supply today. Consumers can easily check for products that have <0.5g per serving of trans fat and avoid comparable products with a higher level of trans fat.

An area of concern is the restaurant area. There are no labeling requirements for trans fat in restaurants and the food service industry. However, several cities have banned the use of partially hydrogenated vegetable oil in restaurants including Boston and New York City.

At the end of 2013, the FDA has proposed to revoke the GRAS status for PHO, effectively eliminating the final 25% of trans fat from our food supply. But that process could take three or more years to complete.

At IOI Loders Croklaan, we have been developing trans fat-free products  based on palm oil since 2004. Palm oil is a natural, cost-effective and versatile solution for PHO and we are currently busy eliminating the last 25% of trans fat from the U.S. food supply.

based on palm oil since 2004. Palm oil is a natural, cost-effective and versatile solution for PHO and we are currently busy eliminating the last 25% of trans fat from the U.S. food supply.

Passwater: Dr. McNeill, thank you for this outstanding primer on dietary fats and human health. We wish you continued success in helping to eliminate harmful trans fat from the diet. Next month, we will continue this subject with a legendary pillar of nutritional science. WF

Dr. Richard Passwater is the author of more than 45 books and 500 articles on nutrition. Dr. Passwater has been WholeFoods Magazine’s science editor and author of this column since 1984. More information is available on his Web site, www.drpasswater.com.

References

1. T. Gordon, et al., “High Density Lipoprotein as a Protective Factor against Coronary Heart Disease. The Framingham Heart Disease Epidemiology Study,” Am, J. Med. 62 (5), 707–714 (1977).

2. R. Mensink, et al., “Effects of Dietary Fatty Acids and Carbohydrates on the Ratio of Serum Total to HDL Cholesterol and on Serum Lipids and Apolipoproteins: A Meta-Analysis of 60 Controlled Trials,” Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 77 (5), 1146–1155 (2003).

3. P. Rebala, “Inside the Changing American Diet,” Time, June 12, 2014, http://time.com/2861385/american-diet, accessed July 17, 2014.

4. K. Oh, et al., “Dietary Fat Intake and Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in Women: 20 Years of Follow-up of the Nurses’ Health Study,” Am. J. Epidemiol. 161, 672–679 (2005).

5. P. Siri-Tarino et al., “Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies Evaluating the Association of Saturated Fat with Cardiovascular Disease,” Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 91 (3), 535–546 (2010).

6. R. Chowdhury, et al., “Association of Dietary, Circulating, and Supplement Fatty Acids With Coronary Risk. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Annals Int. Med. 160 (6), 398-406 (2014).

7. D.J. Baer, “New Findings on Dairy Trans Fat and Heart Disease Risk Center,” presented at IDF World Dairy Summit 2010, Auckland, NZ.

Published in WholeFoods Magazine, September 2014