One of the most important nutrients is the mineral magnesium. It is so basic that its importance can easily be overlooked. Yet, nearly every nutritional researcher I chat with makes a point to include magnesium in our discussions. As examples, I devoted much emphasis to magnesium in my Supernutrition Books. Stephen Sinatra, M.D., made magnesium one of his “Four Pillars.” Fred Kummerow, Ph.D., discussed magnesium in our recent interview (October and November issues). Lendon Smith, M.D., stressed magnesium for nerves.

Just how important is an optimal intake of magnesium and why is it so often overlooked? Let’s pose these questions to the foremost magnesium expert, Andrea Rosanoff, Ph.D., the director of research and science information outreach for the Center for Magnesium Education & Research.

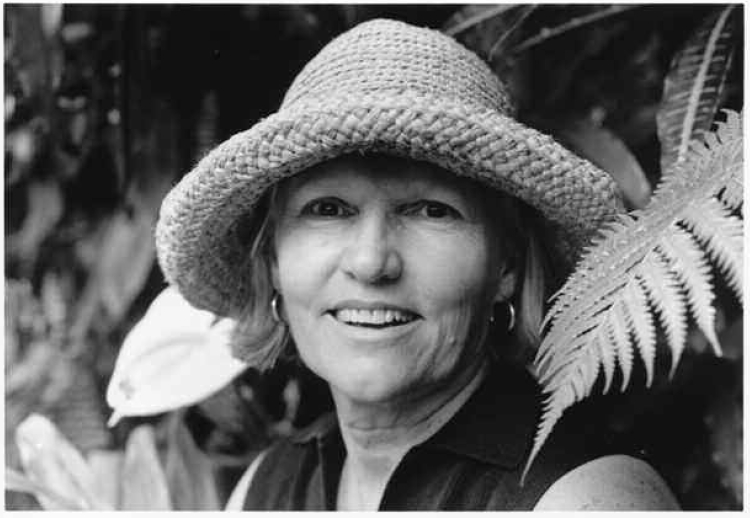

Dr. Rosanoff is a nutritional biologist and director of research at the Center for Magnesium Education & Research, LLC in Pahoa, HI. Dr. Rosanoff spent her undergraduate years at UC Berkeley studying Biological Sciences and then taught science for several years before returning to graduate school. After earning her M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in nutrition from the University of California at Berkeley in 1982, Dr. Rosanoff began her study of nutritional magnesium, especially as it relates to health in the developed world. Her work as senior chemical specialist for Dialog Information Services and information analyst at Chevron Res & Tech Corp. gave her early training of and access to the online scientific literature, which she now uses in her research and teaching on all aspects of nutritional magnesium.

Her main research interests include the development of the nutritional magnesium paradigm of cardiovascular disease, the role of magnesium nutrition in osteoporosis, diabetes, psycho-biological and renal disease, global spreading and generational effect on nutritional magnesium of the processed food diet, and the role of magnesium in stress reactions. Some of her recent publications include studies on changing food crop magnesium concentrations and their possible impact on human health, magnesium supplementation and hypertension and a comparison of magnesium supplements with statin pharmaceuticals.

|

|

| Andrea Rosanoff, Ph.D. |

In addition to her work presented in peer-reviewed journals and at scientific conferences, Dr. Rosanoff is interested in explaining the health aspects of nutritional magnesium to the general public. She co-authored with the late M.S. Seelig, M.D., a book entitled, The Magnesium Factor (published in 2003), which discusses scientific literature through 2002 on nutritional magnesium’s impact on risk factors for cardiovascular disease. In 2008, she wrote, produced and narrated an animated two-minute video entitled, Balancing Calcium and Magnesium, which can be viewed on her Web site (www.MagnesiumEducation.com). Through the Center for Magnesium Education & Research, Dr. Rosanoff continues to foster knowledge about magnesium research: with the Institute of Applied Plant Nutrition, the Center sponsors the International Symposia, bringing together magnesium researchers from all over the world to discuss and present research on magnesium in agriculture and its connection to human nutrition. The Center is also spearheading a group to apply to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a health claim for magnesium in hypertension plus a second effort to reevaluate the serum magnesium reference range.

Passwater: How and why did you become interested in nutrition?

Rosanoff: I remember reading Adele Davis’ book, Let’s Eat Right to Keep Fit, and loving it. Suddenly, I realized that I had no way of discerning whether what she was telling me was right or wrong, and I decided to go to graduate school and learn about nutrition for myself.

Passwater: Why did you specialize in the nutritional minerals?

Rosanoff: When I was working on my master’s degree, I became interested in iron as I was studying a folk remedy for nutritional iron for my thesis (sticking nails into apples was the folk remedy I studied for my M.S. thesis). As I went on for my Ph.D., I continued working on iron, but took corrosion as my minor so I could know more generally about metals and how they interact with foods and soils, etc.

Passwater: What led you to magnesium research?

Rosanoff: About a year or so after I finished my doctorate I was invited to attend a conference where I was to comment on a corrosion process for removing cadmium from wastewater via a corrosion reaction that involved magnesium. To get ready for this conference, I studied up on the toxicity of cadmium and the nutrition of magnesium, and was astounded to find out how important magnesium was and amazed that I had learned essentially nothing about it while in graduate school—even with my focus on minerals. I was hooked, and studying magnesium became a hobby of mine. That was in 1985.

Passwater: You were once an information specialist at Dialog Information Services, a commercial, private information service before the days of the Internet and search engines such as Google and Yahoo. I used the Dialog Information Services extensively in the past. I would guess that having all of that scientific literature at your disposal was helpful to you in uncovering magnesium research ignored by the mainstream.

Passwater: You were once an information specialist at Dialog Information Services, a commercial, private information service before the days of the Internet and search engines such as Google and Yahoo. I used the Dialog Information Services extensively in the past. I would guess that having all of that scientific literature at your disposal was helpful to you in uncovering magnesium research ignored by the mainstream.

Rosanoff: It was indeed. Whenever I wanted (or had time), I could do a search on magnesium and read to my heart’s content. I remember searching the first issue of Prevention magazine and seeing that it featured an article on magnesium. That gave me confidence in focusing on the subject.

Passwater: In my 1977 book on heart disease, I relied heavily on Dialog information for my chapter on magnesium because it was so rich in “hard-to-find” magnesium articles. In those days, research was done in the laboratory or in the Chemical Library. There was no Internet for typing keywords into a search engine and instantly getting results from anywhere. It was hard work, requiring many long hours in the Chemistry Library. A university’s chemical program was only as good as its Chemical Library. Yet, many of those magnesium references were just not found in most libraries. This is why the “new” Dialog Research Services became so important to me. That was 1975–1976. Did you have a hand in putting them in the database then?

Rosanoff: That was “before my time” at Dialog. I started studying nutrition in graduate school in 1976 and didn’t go to Dialog until 1986. But I know what you mean about “hard-to-find” articles. Because magnesium is basic to so many life processes, research on magnesium can be found in all areas of the biological sciences. Gathering these all together became much easier with computerized “online” searching.

Passwater: Most of the magnesium articles then were either about “hard water” and heart disease or basic research by Mildred Seelig, M.D., MPH. You teamed up with Dr. Seelig for your book, The Magnesium Factor, in 1997. How did this collaboration come about?

Rosanoff: When I was at Dialog, I was encouraged to go to scientific conferences to talk with researchers about the benefits of using Dialog for searches in the peer-reviewed literature. At one conference on toxic metals, probably around 1987–88, we were asked what the next big toxic metal health scare was going to be. I geared up my courage and said that too little magnesium was going to be a scare and already was. The man sitting next to me became interested and focused on magnesium at the next environmental metals conference he hosted regularly in Missouri. Dr. Seelig was one of the main speakers, along with three or four other nutrition researchers in magnesium. I was so glad to meet them and spend those days together discussing nutrition and magnesium. I remembered Dr. Seelig several years later, in 1997, when I decided to write a book about magnesium and heart disease, so I called her to interview her. She was delighted to hear that someone wanted to write a book for the lay audience on magnesium, and offered to co-author with me. It was wonderful.

Passwater: Well, Dr. Seelig was certainly one of the main pioneers in magnesium nutrition research. Why did you create the Center for Magnesium Education & Research?

Rosanoff: Around 1997, I began searching  PubMed at home on my personal computer, for free, and I realized how robust the research on magnesium and cardiovascular health was becoming. At the same time, I saw television ads for medicines to treat risk factors for heart disease, and realized that heart patients, doctors and the general public interested in their health deserved and needed to know about the research on magnesium. That was when I decided to upgrade my “hobby” and start studying magnesium in earnest so as to tell people about its potential for health.

PubMed at home on my personal computer, for free, and I realized how robust the research on magnesium and cardiovascular health was becoming. At the same time, I saw television ads for medicines to treat risk factors for heart disease, and realized that heart patients, doctors and the general public interested in their health deserved and needed to know about the research on magnesium. That was when I decided to upgrade my “hobby” and start studying magnesium in earnest so as to tell people about its potential for health.

It was my hope that doctors, once they found out about the research in magnesium, would embrace its use for health and perhaps then want to expand their knowledge into all areas of nutrition. The first job of this new large goal was to study a lot and write the book. A few years later around 2002, just as Mildred and I were finishing up the book, I was at a conference on trace minerals and I had listed “Independent Scholar” on my badge. People asked me what that meant, and seemed worried that I didn’t have a real job. Some even wanted to help me find a job. It seemed a distraction from what I was trying to convey. A friend suggested that I become director of my own research institute so as to have that title when I attended conferences, so I went to a lawyer and started the Center for Magnesium Education & Research, and named myself Directing Scholar. I am now Director of Research & Science Information Outreach.

Passwater: Okay, so educate us. Biochemically speaking, why is magnesium so important to our health? Why is it essential?

Rosanoff: Magnesium is such a fascinating element for life. It is at the center of the chlorophyll molecule so it is essential in the conversion of light energy from the sun into biochemical energy for life processes on Earth. In addition, it is an integral part of adenosine 5’-triphosphate (ATP), a biochemical I call the “batteries of life.” Whenever any reaction of life requires energy, ATP is most likely necessary for that reaction to proceed.

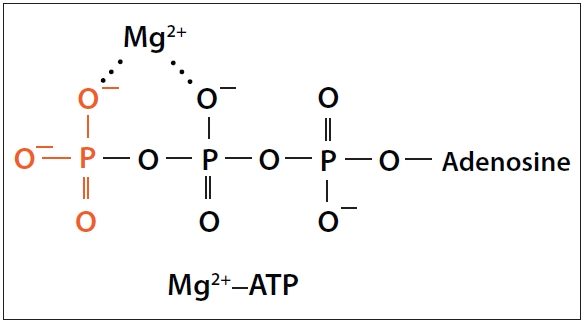

Passwater: Yes, however, it is often overlooked that most ATP in cells exists mostly in a complex with magnesium (Mg2+) as Mg-ATP (1, 2).

Rosanoff: Indeed, magnesium’s role in releasing energy from ATP makes magnesium an important part of almost all human life reactions that require energy. In addition, magnesium itself is a direct cofactor for well over 300 enzymatic reactions involving DNA and RNA synthesis, protein synthesis, glucose uptake and metabolism, just to name a few highlights.

Passwater: Excuse me for interrupting, but I have a slide that I frequently use in my lectures that reads:

ATP = Energy = Life.

Perhaps I should change it to:

Magnesium = ATP = Energy = Life.

This would teach that there is no life without magnesium.

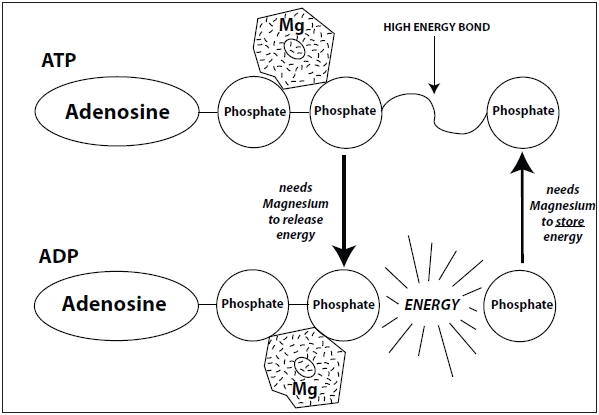

Rosanoff: Figure 1 shows one possible structure of magnesium–ATP and Figure 2 illustrates how magnesium and ATP work together to produce cellular energy.

|

|

|

| Figure 2: Magnesium is required for ATP to release its stored energy to drive important biological reactions in the cells. Artwork by Rebecca Charon, courtesy of Dr. Andrea Rosanoff. |

Passwater: Your Figure 2 clearly shows that magnesium is needed to both charge the ATP “battery” and also release the energy stored in the ATP “battery.” Therefore, few chemical reactions can occur in the body without magnesium and they will proceed optimally for best health only when adequate magnesium is available.

Energy is a physical force, not a chemical compound. Energy can be stored as chemical potential energy in the electronic configuration of a “high energy” bond, a unique bonding of phosphorus (P) and oxygen (O) called a phosphoanhydride bond. In ATP, three phosphate groups are linked to one another by two phosphoanhydride bonds. When one phosphate group is removed by breaking a phosphoanhydride bond in a process called hydrolysis, “free energy” is released, and ATP is converted to adenosine diphosphate (ADP). ADP contains just two phosphates as the name implies. During this process a phosphate group is released into the cell along with the “free energy.” Likewise, “free energy” is also released when a phosphate is removed from ADP to form adenosine monophosphate (AMP).

The important point is that this “free energy” can be transferred to other molecules to make unfavorable reactions in a cell favorable. AMP can then be recycled into ADP or ATP by forming new phosphoanhydride bonds to store energy once again. In the cell, AMP, ADP and ATP are constantly interconverted as they participate in biological reactions.

For those readers who are not chemists, the take-home message is simply that without magnesium, the body either could not—or would have great difficulty—producing the energy needed for life. Essentially, almost every process in the body requires magnesium to release the energy stored as ATP and also the body needs magnesium for more than 300 enzymatic reactions.

For those readers who are not chemists, the take-home message is simply that without magnesium, the body either could not—or would have great difficulty—producing the energy needed for life. Essentially, almost every process in the body requires magnesium to release the energy stored as ATP and also the body needs magnesium for more than 300 enzymatic reactions.

Rosanoff: Correct. Other metal ions with a 2+ charge can also fulfill this role with ATP (e.g., Ca2+ [calcium ion] and Mn2+ [manganese ion]), but magnesium is by far mostly used for this essential life purpose. It would be hard to overestimate magnesium’s importance in enzyme function, both directly as a cofactor and indirectly via ATP reactions.

Passwater: Please explain what an “enzymatic reaction” is for those readers who are not chemists and why enzymatic reactions are required for life.

Rosanoff: In a chemical reaction, one substance changes into another (i.e., A turns chemically into B). Some reactions can only proceed in the presence of a “catalyst” which is a substance that does not change chemically during the reaction (i.e., it is neither A nor B, but it needs to be there for the reaction to happen and for A to turn into B). In living organisms, enzymes (mostly proteins) are biological catalysts, and magnesium ion (Mg2+) is an enabling co-factor for many biological enzymatic reactions in the biochemistry of life.

Passwater: I interrupted you while you were telling us about the roles of magnesium in the body. As far as I’m concerned, the role of magnesium in producing energy is quite enough, but please continue.

Rosanoff: In addition, magnesium is implicated in several physiological processes such as vitamin D biochemistry, hormone synthesis and secretion processes, nerve cell function, digestion and muscle contraction/relaxation. It is part of cell membrane structure including the membranes of mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum which gives cells their internal structure.

Passwater: That certainly makes magnesium one of our most important nutrients. I find it interesting that vitamin D metabolism involves at least eight steps dependent on magnesium. We’ll discuss that in Part 2.

Would it be accurate to say that there are two “types” of magnesium reactions: those driven by magnesium binding to the substrate (i.e., the chemical being acted upon) and those driven by magnesium binding to the enzyme?

Rosanoff: At least. Don’t forget that magnesium is part of the structure of myoglobin (i.e., muscle protein). And it is part of the structure of chlorophyll. There are many functional aspects of magnesium. It appears to have unique properties with its huge radius change from its hydrated to unhydrated forms.

Passwater: How much do we need for optimal health and how much do people get from typical diets?

Rosanoff: In the United States, only about half of the population appears to get their daily requirement of magnesium from the foods they eat, according to the current requirements set by the Institute of Medicine. Some researchers think these requirements are set a bit too high while others think they are way too low for optimal human health, especially humans living in a stressful society such as the contemporary United States. RDAs for magnesium run from about 300 to 420 mg/day for healthy people (teens through elderly adults), but Dr. Seelig who studied magnesium and health for over 40 years believed that intakes of Mg from 425 to 760 mg/day were necessary to maintain health, even more during times of great stress. However, a compilation of some recent human studies from one metabolic study center found that intakes of only 237 mg/day should suffice to maintain health in adult men and women. It’s a controversial topic.

Passwater: There really does seem to be a problem here. Magnesium is so important, especially in reducing the risk of heart disease, yet magnesium appears to be “unappreciated” and so low in typical diets. Why doesn’t the general population realize how important magnesium is and how easy and inexpensive it is to get optimal amounts for optimal health?

Rosanoff: That is a question I have pondered since 1985 when I first learned of the importance of magnesium to human health and realized how magnesium deficient our general population is in its intake with food. I used to think it was some sort of conspiracy, but I no longer do.

I once talked with a plant physiologist who studies plants’ need for magnesium, and she told me the physiology of this essential nutrient for plants is not well studied nor well understood—just like in human physiology. How odd!

I think now that the study of magnesium, which has been done by wonderful researchers over decades, has just “fallen through the cracks” of Western science, and although there is much good, excellent, even inspired peer-reviewed work in this area, the great knowledge from these studies has not made it to the mainstream of our core knowledge. Thus, it is not usually taught as its own large topic of study in biology, nutrition or physiology classes in undergraduate nor graduate and medical/professional education. Since no one is taught about this research, they don’t hold it as part of their core knowledge. So the excellent research that has been done on this fascinating element remains “unknown” to most  people educated in the health and biological sciences.

people educated in the health and biological sciences.

Passwater: Dr. Rosanoff, thank you for this introduction to magnesium and health. Let’s chat more about why magnesium is so important to health in our next column. WF

Dr. Richard Passwater is the author of more than 45 books and 500 articles on nutrition. Dr. Passwater has been WholeFoods Magazine’s science editor and author of this column since 1984. More information is available on his Web site, www.drpasswater.com.

See www.wholefoodsmagazine.com/columns/vitamin-connection for additional Vitamin Connection columns.

References

1. A. Storer and A. Cornish-Bowden, “Concentration of MgATP2− and Other Ions in Solution. Calculation of the True Concentrations of Species Present in Mixtures of Associating Ions,” Biochem. J. 159 (1), 1–5 (1976). PMC 1164030.

2. L. Garfinkel, R. Altschuld and D. Garfinkel, “Magnesium in Cardiac Energy Metabolism,” J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 18 (10), 1003–1013 (1986).

This magnesium series is sponsored by Natural Vitality.

Published in WholeFoods Magazine, February 2015