This month, we continue our conversation with Andrea Rosanoff, Ph.D., about the great importance of the mineral magnesium. In Part One (February 2015), we discussed the importance of magnesium for producing the energy needed for most of the body’s life processes. In Part Two (March 2015), we chatted about how magnesium is needed for the utilization of vitamin D, itself an extremely important vitamin/hormone. This biochemical importance begs the question: Does magnesium make a measurable difference in terms of health and longevity? This month, Dr. Rosanoff discusses the role of magnesium and longevity.

Dr. Rosanoff is a nutritional biologist and the director of research at The Center for Magnesium Education & Research, LLC in Pahoa, HI. Dr. Rosanoff spent her undergraduate years at UC Berkeley studying biological sciences and then taught science for several years before returning to graduate school. After earning her M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in nutrition from the University of California at Berkeley in 1982, Dr. Rosanoff began her study of nutritional magnesium, especially as it relates to health in the developed world. Her work as senior chemical specialist for Dialog Information Services and Information Analyst at Chevron Res & Tech. Corp. gave her early training of and access to the online scientific literature, which she now uses in her research and teaching on all aspects of nutritional magnesium.

Her main research interests include the development of the nutritional magnesium paradigm of cardiovascular disease, the role of magnesium nutrition in osteoporosis, diabetes, psychobiological and renal disease, global spreading and generational effect on nutritional magnesium of the processed food diet, and the role of magnesium in stress reactions. Some of her recent publications include studies on changing food crop magnesium concentrations and their possible impact on human health, magnesium supplementation and hypertension, a comparison of magnesium supplements with statin pharmaceuticals, and the rising calcium to magnesium ratio of dietary intakes in the United States.

|

|

| Andrea Rosanoff, Ph.D. |

In addition to her work presented in peer-reviewed journals and at scientific conferences, Dr. Rosanoff is interested in explaining health aspects of nutritional magnesium to the general public. She co-authored with the late M.S. Seelig, M.D., a book entitled, The Magnesium Factor (published in 2003), which discusses scientific literature through 2002 on nutritional magnesium’s impact on risk factors for cardiovascular disease. She wrote, produced and narrated an animated two-minute video entitled, Balancing Calcium and Magnesium in 2008, which can be viewed at her Web site (www.MagnesiumEducation.com). Through the Center for Magnesium Education & Research, Dr. Rosanoff continues to foster knowledge of magnesium research; with IAPN the Center sponsors International Symposia bringing together magnesium researchers from all over the world to discuss and present research on magnesium in agriculture and its connection to human nutrition. The Center is also spearheading a group to apply to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a health claim for magnesium in hypertension plus a second effort to reevaluate the serum magnesium reference range.

Passwater: Dr. Rosanoff, before we look at aging itself, let’s take a quick look at a couple of studies showing greatly reduced risk of dying from disease. A 2011 study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition that may interest many readers is that magnesium greatly lowers the risk of sudden cardiac death (1). Please tell us about this study.

Rosanoff: That study and a 2013 study show that low dietary and plasma magnesium are each associated with heart health risk and sudden cardiac death risk (1, 2). The 2011 study by Stephanie E. Chiuve, Sc.D., and colleagues dramatically showed that higher plasma magnesium (2.1 mg/dL versus 1.9 mg/dL) lowers the risk of sudden cardiac death by 77%, and that for each 0.25 mg/dL increase in plasma magnesium, the risk of sudden cardiac death dropped by 41%.

These findings actually confirm a large body of older peer-reviewed science on the robust and essential role of nutritional magnesium in preventing cardiovascular diseases. So, this is not a “new” discovery, but rather a “rediscovered” discovery. As early as 1957, a Japanese study showed that when hardness of drinking water went up in a community, the rate of death from cardiovascular disease went down in that community.

This early work has been confirmed many times in several communities all over the world, and the factor in the water’s “hardness” has been shown to be magnesium and perhaps the calcium-to-magnesium ratio (Ca:Mg ratio). The list of such studies is vast. I cited 27 peer-reviewed articles, published between 1969 and 2012, in a paper showing how high-magnesium drinking water lowers sudden cardiac death and heart disease in communities (3).

In 1980, Mildred Seelig, M.D., published a comprehensive book on this subject with a 78-page bibliography of the peer-reviewed literature (4). One of the best general articles about magnesium and human health was the first article published in the first volume of the journal Magnesium in 1982 (5). Unfortunately, this classic paper, written by Dr. J.R. Marier, is not in PubMed because the first two years of Magnesium were never indexed in this database. The article clearly shows how magnesium intakes are low in the modern-day world and reviews the early literature showing the importance of magnesium in heart health.

In the 1990s, magnesium treatment for heart attack was studied with very good effects in several small studies (n = 273–2,316 patients getting an influx of magnesium during heart attack), but when the larger studies were conducted, there was statistically “no change” with added magnesium influx or even a slight rise in death rates of these hospitalized heart attack patients. These results pretty much ended the use of magnesium for heart health at the time, which was the same era when anti-hypertension medications (e.g., Ca-channel blockers and ACE inhibitors) were coming into wide use. In fact, many heart patients were taking these medications during the later studies. Several of these medications are magnesium-sparing agents (not the diuretics, unfortunately, which have the opposite effect, meaning they cause increased loss of magnesium in the urine), and it is thought that this change in the subject population had an effect on how magnesium treatment shows up in studies of this kind.

Today, magnesium use is becoming more and more common during heart treatment, along with medications like statins. There are some calls to treat many people with these medications as a preventive of heart disease, but I believe that the science still strongly suggests that adequate magnesium nutrition and appropriate balance of calcium and magnesium intakes of 1.7–2.8 to 1 (Ca:Mg) is probably the best way to prevent cardiovascular disease. After all, as so well laid out by Dr. Marier back in 1982, the modern processed food diet is largely low in magnesium, being high in refined foods and low in seeds, nuts and whole grains.

For a few generations now, we have been on a low or marginal magnesium diet. Magnesium is such an important nutrient, essential in so many basic physiological and biochemical processes that its physiology is elusive: the body appears to adapt to this chronic low magnesium intake by “spreading out” the body’s store of magnesium, keeping blood magnesium levels in what is considered the “normal, healthy” range even when body stores and even bone magnesium might be getting low. Replenishing these body stores via a high magnesium diet, added supplements or both is a wise and largely safe way to go.

For a few generations now, we have been on a low or marginal magnesium diet. Magnesium is such an important nutrient, essential in so many basic physiological and biochemical processes that its physiology is elusive: the body appears to adapt to this chronic low magnesium intake by “spreading out” the body’s store of magnesium, keeping blood magnesium levels in what is considered the “normal, healthy” range even when body stores and even bone magnesium might be getting low. Replenishing these body stores via a high magnesium diet, added supplements or both is a wise and largely safe way to go.

Many may wonder, how can I tell what my body stores of magnesium are? Are they adequate, marginal or low? Unfortunately, we do not have a functional biomarker for whole-body magnesium status. I wish we did, as research on this important nutrient would be much facilitated. We often use total serum magnesium as a marker when actually it can be misleading, being in the “normal” range when body stores of magnesium are in fact low.

Some practitioners are knowledgeable in the use of intracellular magnesium level tests and a select few use ionized serum magnesium, but these measurements can be expensive and are not widely available. Doctors mostly seem to order serum magnesium, if they order any magnesium blood work at all. Unfortunately, the “normal” range for serum magnesium may be too wide on the lower side. A patient’s serum magnesium level may appear to be in the “normal” range, when it is actually “low.”

The serum magnesium reference range in the United States is based upon large studies of serum magnesium in the general population from 1971–1974, and it was assumed that it represented the range of serum magnesium in normal, healthy people. Since there is no reliable biomarker for the adequacy of a person’s magnesium stores, these 1974 serum magnesium values are quite likely those of people at all levels of magnesium body stores—low, medium and high.

Research is beginning on re-evaluating the normal range for serum magnesium, based upon research into serum magnesium levels during various states of health including biomarkers for cardiovascular health such as C-reactive protein and LDL cholesterol as well as disease states such as type-2 diabetes. We hope to define a serum magnesium reference range that reflects more of the health findings that recent magnesium research has uncovered; rather than using just the wide range of undifferentiated values found in the population 40 years ago.

So, without a reliable, individual marker for magnesium status, how does one know if one should be taking a magnesium supplement? Well, since our diets are generally quite low, and since oral magnesium supplements are quite safe, the simplest way to see if you need more magnesium is to try a supplement and see if the condition in question improves.

There are several placebo-controlled clinical studies where only oral magnesium has been given, with positive results for such conditions as high blood pressure, type-2 diabetes, irregular heart beat and atrial fibrillation, tearfulness, sleep disorders, nervousness and irritability, mental fatigue and physical fatigue. In addition, such studies with oral magnesium have shown improvements in HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, blood triglycerides, sodium excretion, red blood cell magnesium and the raising of intracellular magnesium and potassium with simultaneous decrease in intracellular calcium and sodium.

For many, trying a magnesium supplement may be easier, quicker and less expensive than trying to get rigorous biomarker test results and having them properly interpreted, however for serious chronic conditions, it is always helpful to have a good practitioner knowledgeable in magnesium and other nutrients.

Some people add a magnesium supplement to their general lifestyle. I am one of those, and I found I needed to “up” my dose of daily magnesium when I turned 70. People with a high stress lifestyle or family history of heart disease will most likely need higher doses of daily magnesium to retain their heart health. There is also evidence that this same optimal magnesium and calcium nutrition can help prevent other chronic diseases of aging such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, type-2 diabetes and some cancers.

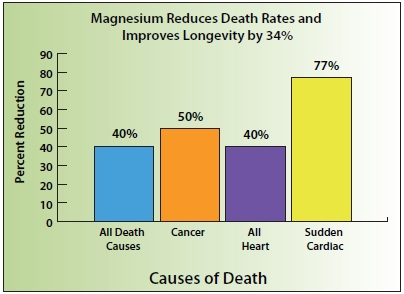

Passwater: Magnesium improves lifespan by reducing death from all causes, including heart disease and cancer. Please tell us about the 2014 Journal of Nutrition study that showed how dramatic the effect is (6).

|

|

| Figure 1: Studies associate higher levels of magnesium with a 34% improved longevity and reduced death rates when compared to lower levels of magnesium. Optimal magnesium levels lower risk of death from all causes by 40%, cancer by 50%, all forms of heart disease by 40% and sudden cardiac death by 77%. |

Rosanoff: Interesting recent studies have been conducted in Spain on people who were at risk for cardiovascular disease (6, 7). These subjects’ baseline magnesium intakes—after being followed for about five years on a Mediterranean diet especially high in either nuts (a high magnesium food) or extra-virgin olive oil (may be high in magnesium)—were predictive of future health, as those with the highest magnesium intakes were definitely healthier, showing

• 40% lower risk of death from all causes

• 50% lower risk of death from cancer

• 40% lower risk of death from cardiovascular disease.

Studies have been pretty consistent, even though some focus on dietary magnesium intake, others focus on serum magnesium. It is really amazing that such statistically significant results are being found with these studies since the dietary intake of minerals is a pretty “soft” measurement (compared to a biochemical such as total cholesterol for example) and difficult to collect accurately and precisely. Total serum magnesium, while being useful as a research tool, is often not always a reliable predictor of an individual’s magnesium status, as previously noted. Even with these experimental shortcomings, lower death rates with either higher serum, plasma or dietary magnesium are being shown.

One meta-analysis (i.e., a collection of several studies, in this case 16 studies), showed that when dietary magnesium goes up, the risk of death by cardiovascular disease and cardiovascular disease itself goes down (8). For blood magnesium, combining these studies showed that higher circulating magnesium levels significantly lower the rates of sudden cardiac death.

Passwater: Various studies show the same trend, but the numbers differ somewhat because some look at dietary intake and others analyze blood levels, some look at the statistics from a magnesium “deficiency” point of view, whereas others just divide the levels into groups and some use different magnesium levels for cut-off points. One study not only looks at risks of death, but also hospitalization. What does the Adamopoulos study teach us?

Rosanoff: The Adamopoulos study found that patients with low serum magnesium (i.e., equal to or less than 2 mEq/L) were at

• 23% higher risk of death from all causes

• 38% higher risk of death from cardiovascular disease

• 18% higher risk of hospitalization for all causes

• 14% higher risk of hospitalization for cardiovascular disease (9).

Passwater: A 2012 study showed similar results on magnesium and aging (10). What were its findings?

Rosanoff: The study by Dr. W.J. Rowe showed that those with the highest magnesium intake had a 34% improvement in lifespan compared with those having the lowest intake (10).

Passwater: Okay, now let’s get to magnesium and the aging process itself. If we can slow the aging process, we can live better longer. One very good indicator of cellular functional age is telomere length. Cells can only replicate properly if they have an adequate amount (length) of telomeres, which are DNA fragments that protect the ends of chromosomes from deterioration. Telomeres can be likened to aglets, the plastic tips that bind the ends of shoelaces to keep them from fraying. Telomeres help keep chromosomes intact much like aglets keep shoelaces intact. As cells replicate over time, the telomeres gradually shorten and the chromosomes lose some of their protection. As telomeres become shorter, eventually cells reach the limit of their replicative capacity, no longer divide or function, and die.

Telomeres can be thought of as being “countdown clocks” that determine how long you’ll live. By slowing the countdown, it is thought that people may be able to extend their lifespan and feel younger longer. Studies show that the shorter your telomeres are, the “older” your body is, regardless of your actual age. Shorter telomeres are not only associated with poorer health and biological aging, but also, in particular, white blood cell telomere length (considered to be the main infantry of our bodies’ defenses) has been shown to predict survival rates among people with cardiovascular disease.

Rosanoff: The good news is that magnesium is indeed involved in the maintenance and repair of telomeres. Two research reports to illustrate this have been published by Dr. Y. Sakaguchi and colleagues (11) and Drs. D.W. Killilea and B.N. Ames (12). But, there is more good news along with a caution: longevity in humans is increasing in 187 countries—that’s a pretty widespread trend in longer life (13). That’s the good news. The caution is that with longer life expectancy, it is even more important for all of us to practice prevention with good, solid nutrition. As we get these “extra years,” how will they be for us? They might be healthy or filled with pains, perhaps recovering from a stroke or heart condition, or some other chronic discomfort. Good nutrition, including all 44 essential micronutrients that humans need in adequate and balanced amounts, is what gives all of us the best chance that these “extra prize” years will be lived in health.

Passwater: Well, there are many more studies that we could include, but I think this is sufficient to give our readers a look at the big picture on how important magnesium is to lifespan.

In Part One, we discussed how magnesium is critical to energy production via ATP and over 500 other enzymatic reactions critical to life. In Part Two, we examined how magnesium is required for the utilization of vitamin D. Now, in this discussion we have looked at studies showing that magnesium improves longevity and slows the aging process. We noted that:

1. Optimal magnesium levels lower the risk of sudden cardiac death by 77% and lower the risk of death from all forms of cardiovascular disease by 40%.

2. In fact, optimal magnesium levels lower risk of death from all causes by 40%, including a 50% lower risk of death from cancer.

3. Optimal magnesium intake produces a 34% improvement in lifespan compared with those having low intake.

4. Magnesium is required for the process that maintains and lengthens telomeres, a major indicator of cellular health and longevity.

These results of these studies are summarized conceptually in Figure 1.

Let’s take a break and continue next time with a closer look at magnesium and cardiovascular health. Thanks for chatting with us once again about magnesium and health. Readers may find more interesting facts on Dr. Rosanoff’s Web site at www.MagnesiumEducation.com. WF

Dr. Richard Passwater is the author of more than 45 books and 500 articles on nutrition. Dr. Passwater has been WholeFoods Magazine’s science editor and author of this column since 1984. More information is available on his Web site, www.drpasswater.com.

See www.wholefoodsmagazine.com/columns/vitamin-connection for previous Vitamin Connection columns.

This editorial series is sponsored by Natural Vitality.

References

1. S.E. Chiuve, et al., “Plasma and Dietary Magnesium and Risk of Sudden Cardiac Death in Women,” Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 93 (2), 253–260 (2011).

2. L.C. Del Gobbo, et al., “Circulating and Dietary Magnesium and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Of Prospective Studies,” Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98 (1), 160–173 (2013).

3. A. Rosanoff, “The High Heart Health Value of Drinking-Water Magnesium,” Med. Hypotheses. 81 (6), 1063–1065 (2013).

4. M. Seelig, “Magnesium Deficiency in the Pathogenesis of Disease,” NATO Advanced Study Institutes Series: Series B, Physics, Aug. 31, 1980.

5. J.R. Marier, “Quantifying the Role of Magnesium in the Interrelationship between Human Mortality/Morbidity and Water Hardness,” Magnesium 4 (2–3): 53–59 (1985).

6. M. Guasch-Ferre, et al., “Dietary Magnesium Intake Is Inversely Associated With Mortality in Adults a High Cardiovascular Disease Risk,” J. Nutr. 144 (1), 55-60 (2014).

7. M. Guasch-Ferre, et al., “Frequency of Nut Consumption and Mortality Risk in the PREDIMED Nutrition Intervention Trial,” BMC Med 11, 164 (2013).

8. L.C. Del Gobbo, et al., “Circulating and Dietary Magnesium and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies,” Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 98 (1), 160–173 (2013).

9. C. Adamopoulos, et al., “Low Serum Magnesium and Cardiovascular Mortality in Chronic Heart Failure: A Propensity-Matched Study,” Int. J. Cardiol. 136 (3), 270–277 (2009).

10. W.J. Rowe, “Correcting Magnesium Deficiencies May Prolong Life,” Clin. Interv. Aging 7, 51–54 (2012).

11. Y. Sakaguchi, et al., “Hypomagnesemia Is a Significant Predictor Of Cardiovascular and Non-Cardiovascular Mortality in Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis,” Kidney Int. 85 (1), 174–181 (2014).

12. D.W. Killilea and B.N. Ames, “Magnesium Deficiency Accelerates Cellular Senescence In Cultured Human Fibroblasts,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 5768–5773 (2008).

13. H. Wang, et al., “Age-Specific and Sex-Specific Mortality in 187 Countries, 1970-2010: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010,” The Lancet. 380, 2071–2094 (2012).

Published in WholeFoods Magazine, April 2015