So what’s new? Let’s ask Dr. William Harris. He was kind enough to discuss the Omega-3 Index with us in 2011, Omega-3s and the risk of Cardiovascular Disease in 2012, and Fish Oils and Prostate Cancer in 2013, so I have called upon him again to update us on new findings on fats.

Dr. William Harris is one of the world’s leading omega-3 researchers. He holds a Ph.D. in nutritional biochemistry from the University of Minnesota and began his omega-3 research in 1979 as a post-doctoral fellow in the laboratory of William Connor, M.D., at the Oregon Health Services University (Portland). Dr. Connor was a leading researcher at the time in nutrition, lipids (fats) and heart disease. Dr. Harris’ early research centered on the possible effects of large quantities of salmon oil on blood cholesterol.

Dr. Harris was the director of the Lipid Research Laboratories at the University of Kansas Medical Center (KUMC) and at the Mid America Heart Institute, both in Kansas City, MO, for 22 years, and was on the faculty at KUMC and at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine. Between 2006 and 2011, he was the director of the Cardiovascular Health Research Center at Sanford Research/USD (Sioux Falls, SD).

Dr. Harris’s research has focused primarily on omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. He has been the principal investigator on five omega–3-related NIH grants, and is currently evaluating omega-3 blood tests as a possible new risk factor for cardiovascular disease. In 2004, he and his colleague Clemens von Schacky proposed that the Omega-3 Index be considered as a new cardiovascular risk factor, and in 2009, he founded OmegaQuant Analytics, LLC to offer the test commercially. He retains an academic appointment as professor of medicine at the Sanford School of Medicine, University of South Dakota in Sioux Falls and serves as the Chief Scientific Officer for OmegaQuant.

Over the years, Dr. Harris has published many major research articles and reviews on the marine lipids, EPA and DHA. A major discovery of Dr. Harris and his colleagues has been the elucidation of the Omega-3 Index as a risk factor in cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Harris’ leadership role in omega-3 research was the reason that Dr. Jørn Dyerberg (the discoverer of fish oil’s role in reducing cardiovascular risk) and I asked Dr. Harris to write the foreword to our 2012 book, “The Missing Wellness Factors: EPA and DHA” (Basic Health Publications, Laguna Beach, CA).

Although during his career, he has focused on omega-3 fatty acids, Dr. Harris has also conducted research on the health effects of other families of fatty acids, notably trans fats and the cousins to the omega-3s, the omega-6 fatty acids. As regards the latter, he was the lead author on the American Heart Association’s 2009 Science Advisory on Omega-6 Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Health (1). Dr. Harris was a member of the research team that just published a new study on omega-6 and heart disease, and it is that study that will be the focus of this article.

Passwater:Dr. Harris, how has your recent study contributed to our understanding of fatty acids?

Harris:Our recent meta-analysis (a study that combines the results of many other studies) found that higher blood levels of the omega-6 fatty acid linoleic acid (LA) were associated with lower risk for developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) (2). This suggests that, contrary to popular wisdom, this major omega-6 fatty acid is good, not bad, for our health.

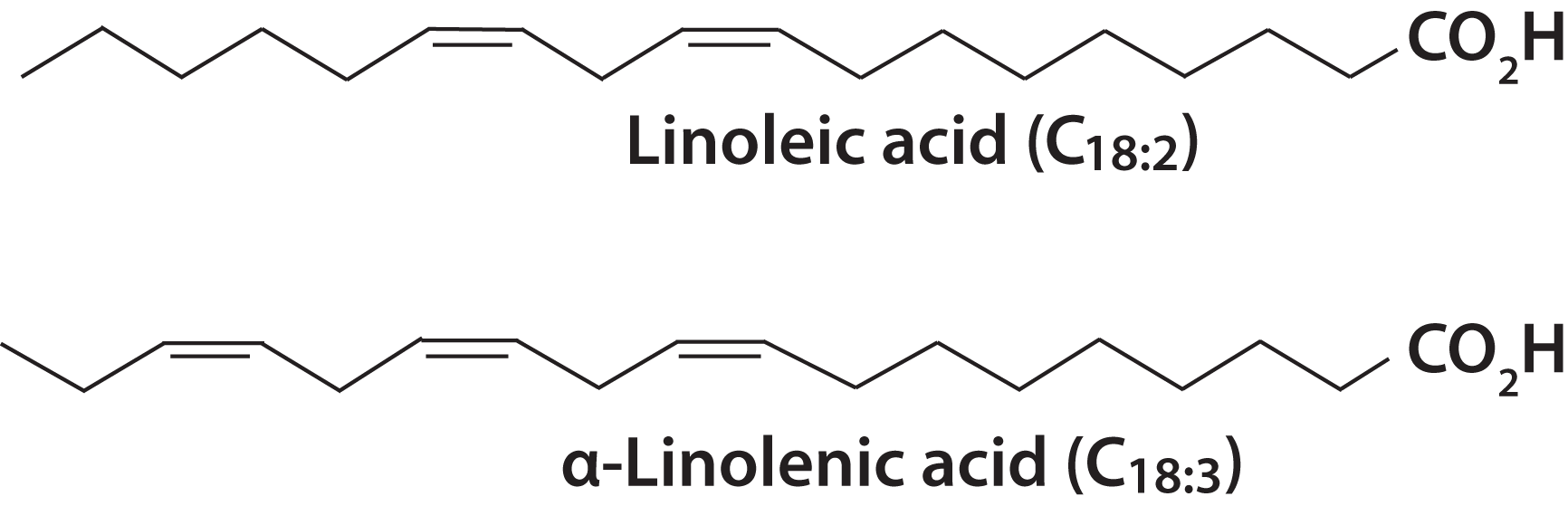

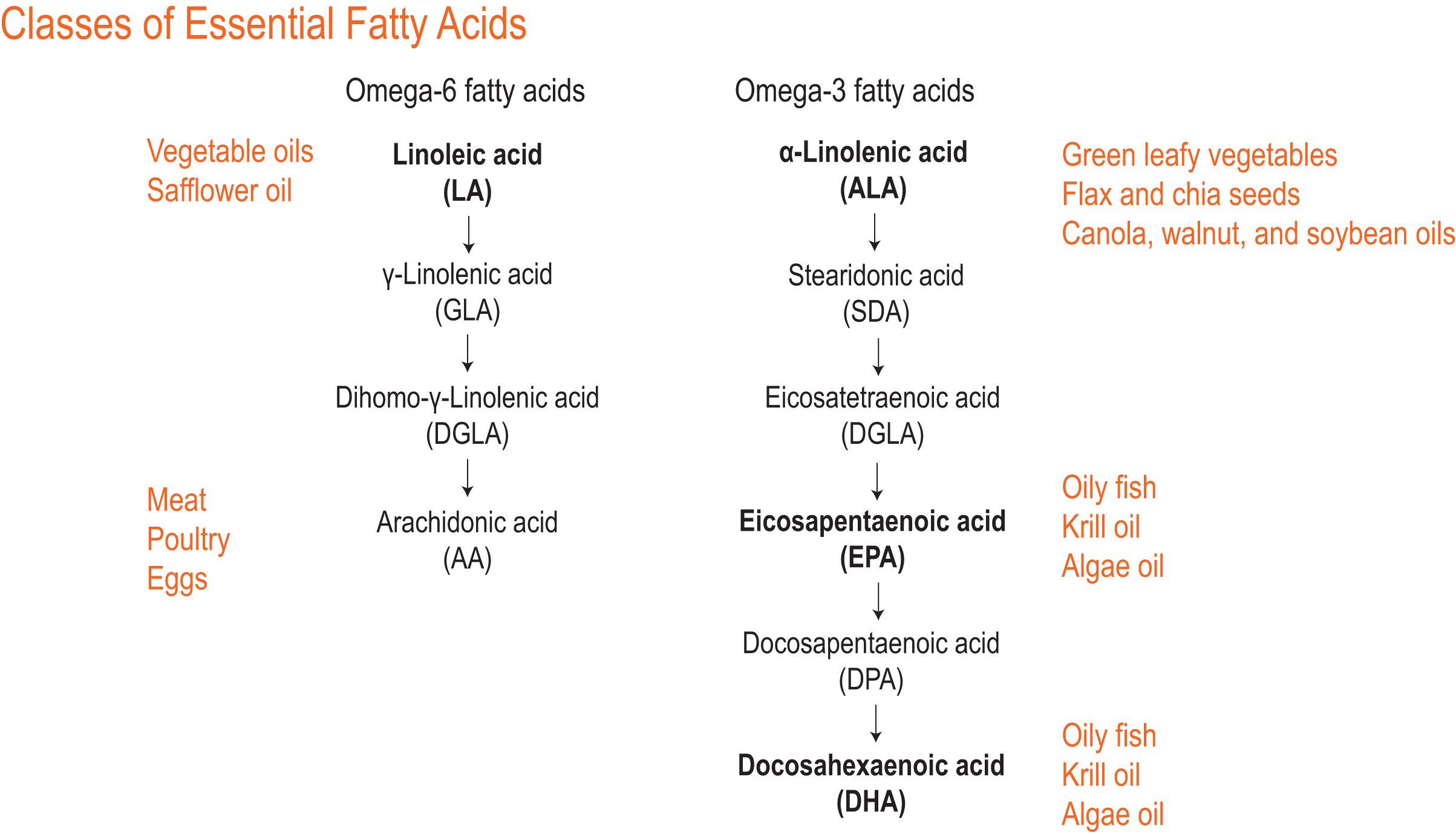

Passwater:Linoleic acid, one of two polyunsaturated fatty acids recognized as being a dietary essential, has an 18-carbon chain with two double bonds in an omega-6 configuration (i.e., the first double bond is 6 positions in from the left—or “omega”—end of the molecule. (Please see Figure 1.) The technical structural name for linoleic acid is octadecadienoic acid, but hardly anyone, even chemists and nutritionists, call it by its technical name. The other dietary essential fatty acid is alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), which is also an 18-carbon chain, but it has three double bonds in an omega-3 configuration. Dr. Harris, my co-author Dr. Jørn Dyerberg, and myself are included among scientists who are making the case for eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) to also be considered as being dietary essentials. Figure 2 lists the common fatty acids grouped into omega-6 and omega-3 classifications.

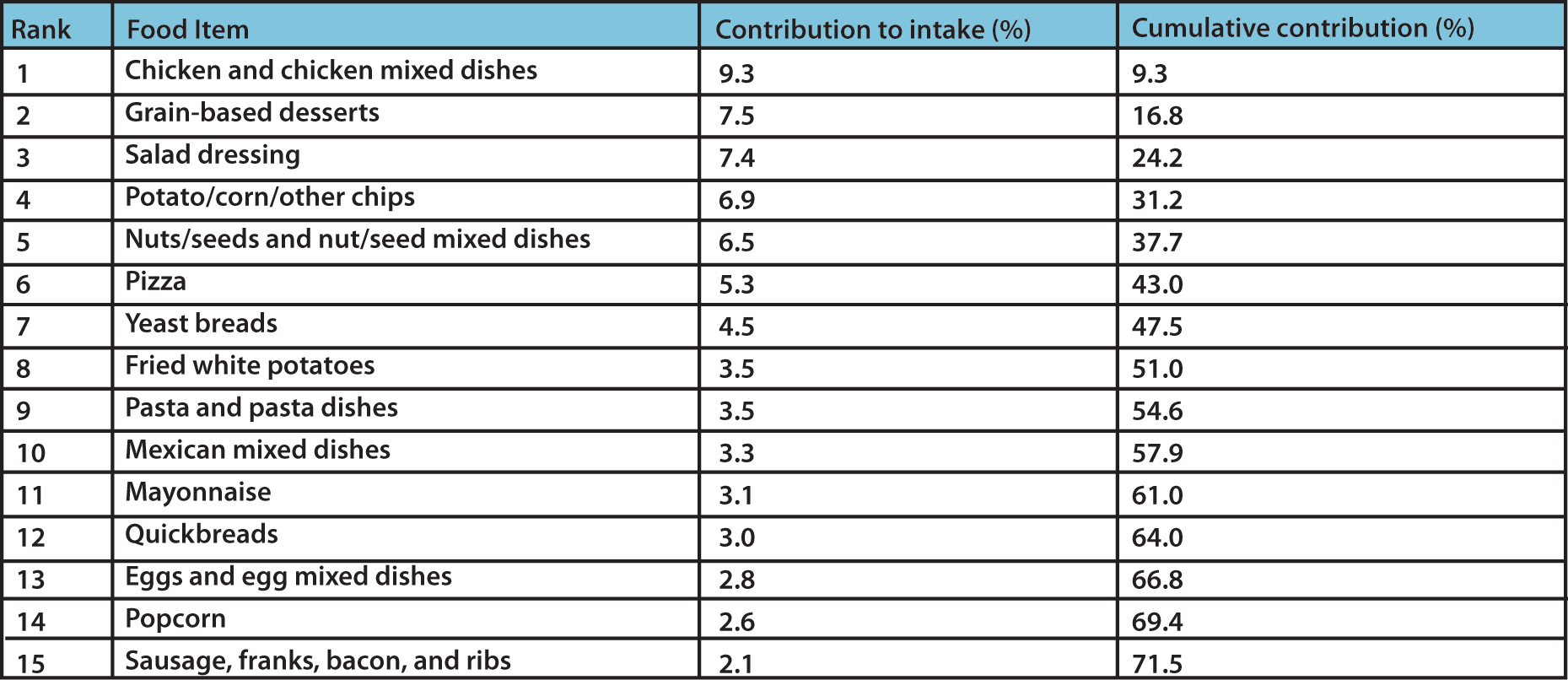

Chicken, corn and seed oils are the main sources of linoleic acid in the American Diet, and it is plentiful in many diets, whereas EPA and DHA are relatively scarce in the Western Diet. (Please see Table 1.)

Please tell us about this new study.

Harris:The latest study, published in April 2019 in the American Heart Association’s flagship journal, Circulation, used data from 30 prospective observational studies from 13 countries involving about 69,000 people. [Note: an “observational” study is one in which the investigators essentially “watch” what happens to people over time; an “interventional” study is where investigators treat people with drugs or medicines and then see what happens over time.] These are all studies that measured blood levels of LA (and arachidonic acid, AA, another omega-6 fatty acid) at the baseline, and then followed people for the development of CVD over the next 5-30 years.

The basic hypothesis being tested was this: If LA is bad for health (as some have taught) then people with higher blood levels of LA would, over time, be more likely to develop CVD (i.e., have a heart attack or stroke). What we found was the opposite: People in the top 10% of LA levels at baseline (i.e., those with the highest levels) were 7% less likely to develop any CVD and 22% less likely to die of CVD.

They were also 12% less likely to have an ischemic stroke (i.e., blocked brain artery) compared with those in the bottom 10% of blood LA levels. In other words, higher LA levels were associated with better cardiovascular health. It has been long known that higher intakes of LA lower levels of LDL (or ‘bad’) cholesterol, but this new research extends that to improved overall CV health. This means that, again contrary to what many have taught, LA is good for the heart, not bad, and efforts to lower LA intakes are more likely to cause long-term harm than help.

Passwater:Hasn’t there been some concern about LA being converted in the body to pro-inflammatory AA?

Harris:Yes, this has been the dogma for some time, but it’s beginning to fall apart. In our study described above, we also measured AA levels in the blood at baseline. If it were true that higher levels were bad for heart health, we would have seen that those people with the highest levels of AA would be at increased risk for CVD over time. We did not find this; we found that AA levels were unrelated to risk for CVD—not good and not bad. So, our study did not find evidence that AA was bad for heart health.

In addition, we now know that AA is also the starting material for important anti-inflammatory molecules, so one cannot paint AA simply as a pro-inflammatory fatty acid.

Passwater:Hasn’t there been some concern about too much LA disrupting the omega-6 to omega-3 (n6:n3) ratio?

Harris:The n6:n3 ratio was originally thought of as a good marker of “omega balance,” with lower ratios being better. While this made some sense in the 1980s, the accumulation of new data over the last 40 years has shown this ratio to be out of date and essentially useless (or uninformative) (3).

There are several reasons for this. First, the ratio is based on invalid assumptions. Beyond the omega-6 fatty acids having both pro- and anti-inflammatory properties and being good—not bad—for the heart (and for developing diabetes as shown in a similarly-designed earlier study) (4), higher intakes of LA do not raise blood AA levels.

Other problems include the fact that the individual fatty acids that make up the n6:n3 ratio can vary from study to study and are rarely defined. Also, the lipid pool (whole blood, plasma, red blood cells) all have different n6:n3 ratios, and these are all different from the dietary ratio.

Finally, identical ratios can be calculated from an endless variety of individual FA levels. In other words, you can have a ratio of 10 (for example) with both very high and very low levels of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. So, the ratio approach is useless for giving dietary guidance.

The overwhelming “omega” problem in the American diet is the lack of EPA and DHA—not the presence of omega-6 (LA). So, focusing on getting more EPA+DHA from fish or supplements is job #1. “Ratio” thinking leads one to believe that if you lower your LA intake you can achieve the same benefits as raising your EPA+DHA intake, and that is clearly wrong.

Passwater:What are your recommendations?

Harris:From a dietary point of view, we recommend maintaining the current American LA intakes of 5%-10% of kcalories. This means, for example, not substituting canola or olive oil for corn or soybean oil (because that will lower your LA intake). As far as the omega-3 fatty acids go, we recommend aiming for an EPA+DHA intake of 500-1000 mg per day (which is 5-10x current American intakes). This will have a measurable impact on a blood marker of omega-3 status, the Omega-3 Index (red blood cell EPA+DHA) which is the best overall barometer of omega-3 status available.

Passwater:Any other new studies on the health benefits of EPA/DHA on heart and/or arteries?

Harris:We recently published a study showing that the Omega-3 Index is a more sensitive predictor of increased risk for CVD (and premature death from any cause), than is serum cholesterol, the most well-known risk factor (5). This does not mean that cholesterol should not be measured, and its levels optimized (via diet and drugs if necessary), but that the Omega-3 Index should also be measured if you want a more complete picture of your personal risk for CVD.

In three major interventional trials reported in late 2018, omega-3 fatty acid treatment significantly reduced risk for vascular death (6), myocardial infarction (7), and major adverse CV events (8). The latter study was particularly compelling as it used 4 g of EPA (as opposed to the usual 0.84 g of EPA+DHA in the other two studies) in statin-treated patients and found a major, 25% risk reduction in CVD events. Hence, the most recent data support a role for omega-3 FAs in reducing risk for CVD.

Passwater:Any other new studies on DHA and pregnancy?

Harris:Yes. A new meta-analysis reported that low levels of DHA in the blood of pregnant women is now recognized as a “modifiable risk factor” for preterm birth, especially early preterm birth (9). Our studies have defined a red blood cell DHA level of less than 5% as too low. There is also now a test that pregnant women and their doctors can use to measure the RBC DHA level using only one drop of blood (Prenatal DHA test, available from OmegaQuant). In this way, pregnant women can take control of at least one factor (but there are many, most unknown at present) that can reduce their risk for delivering prematurely. Once a mother delivers her baby, she is always encouraged to breastfeed as this provides optimal nutrition for the baby. But if mom does not eat much DHA, then her milk DHA levels will be low, and her baby will not receive optimal amounts of DHA for brain and eye development. OmegaQuant also offers a Mother’s Milk DHA test that, from a single drop of breast milk, her milk DHA level can be determined. If it’s low, it’s very easy to “fix” by just consuming more DHA (fish or supplements).

Passwater:In review, are the following accurate?

- LA is good for CVD health;

- AA does not harm CVD health—it’s neutral;

- The typical American does not consume adequate EPA and DHA for optimal CVD health;

- The Omega-3 Index is an excellent indicator of your personal omega-3 levels;

- The Prenatal DHA test can help pregnant women reduce their risk for premature delivery; and

- The Mother’s Milk DHA test can help a new mom optimize her milk DHA level.

Passwater:What is the take home message from the new studies?

Harris:I think on the cardiovascular front, the press has recently been pounding us with the message that omega-3 fatty acids “don’t work” to reduce risk for heart disease. We now know that those proclamations were inaccurate because they were based on studies that gave too little EPA+DHA too late in life and for too short a period. Omega-3s do “work”—you just must take enough to raise the Omega-3 Index into the healthy, target zone of 8%-12%, and then keep them there.

Passwater:Dr. Harris, let’s chat more about the omega-3 fats in fish oil, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) next month.WF

References 1. Harris WS, Mozaffarian D, Rimm EB, et al. Omega-6 Fatty Acids and Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: A Science Advisory from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation. 2009;119:902-907. 2. Marklund M, Wu JHY, Imamura F, et al. Biomarkers of Dietary Omega-6 Fatty Acids and Incident Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality: An Individual-Level Pooled Analysis of 30 Cohort Studies. Circulation. 2019. 3. Harris WS. The Omega-6:Omega-3 ratio: A critical appraisal and possible successor. Prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and essential fatty acids. 2018;132:34-40. 4. Wu JHY, Marklund M, Imamura F, et al. Omega-6 fatty acid biomarkers and incident type 2 diabetes: pooled analysis of individual-level data for 39 740 adults from 20 prospective cohort studies. The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology. 2017;5:965-974. 5. Harris WS, Tintle NL, Etherton MR, Vasan RS. Erythrocyte long-chain omega-3 fatty acid levels are inversely associated with mortality and with incident cardiovascular disease: The Framingham Heart Study. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12:718-724. 6. Bowman L, Mafham M, Wallendszus K, et al. Effects of n-3 Fatty Acid Supplements in Diabetes Mellitus. The New England journal of medicine. 2018;379:1540-1550. 7. Manson JE, Cook NR, Lee IM, et al. Marine n-3 Fatty Acids and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease and Cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 2018. 8. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al. Effects of Icosapent Ethyl on Total Ischemic Events: From REDUCE-IT. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019. 9. Middleton P, Gomersall JC, Gould JF, Shepherd E, Olsen SF, Makrides M. Omega-3 fatty acid addition during pregnancy. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2018;11:CD003402.

Note: The views and opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and contributor(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the publisher and editors of WholeFoods Magazine.