Autumn weather encourages sports participation on both the professional and weekender levels. Exercise is needed for health and fitness, but our bodies have limits. Humans are not well-designed for the excessive repetitive motions that are required for most sports. Simple advice such as “don’t overdo it” is wasted due to our competitive nature. Professionals have no choice and weekenders simply trying to have a little fun usually get a little competitive and often end up with sore muscles. While this may be inconvenient to the weekend athlete, it can be career-threatening to the professional.

The good news is that nutrition can greatly reduce injuries and soreness, while improving performance at the same time. The competitive athlete may find expert advice on this subject hard to come by. Even professional teams are often lacking in modern sports nutrition advice beyond “eat more chicken and less junk.” Fortunately, this month we are able to chat with exercise physiologist, Malachy McHugh, Ph.D., and learn how to increase performance, reduce injury and soreness. One of Dr. McHugh’s findings is that cherry juice prevents and relieves muscle inflammation and soreness.

Dr. McHugh received his Ph.D. in exercise physiology in 1999 from the University of Wales, Bangor. Since 1999, Dr. McHugh has been the director of research at the Nicholas Institute of Sports Medicine and Athletic Trauma (NISMAT) at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. He leads a multidisciplinary research team including orthopaedic surgeons, physical therapists, exercise physiologists, nutritionists, biomechanists, biomedical engineers and athletic trainers. The research encompasses areas such as randomized clinical trials in orthopaedic sports medicine, injury epidemiology, and basic and applied research in nutrition, physiology, and biomechanics. Dr. McHugh is a fellow of the American College of Sports Medicine and a member of the Orthopadeic Research Society. He is an adjunct professor in the department of physical therapy at New York University and has also held teaching positions in the department of physical therapy at Stony Brook University and the department of physical education at Hunter College in New York City. He has been a consultant with the New York Rangers hockey team since 2000. Dr. McHugh’s varied research interests include exercise-induced muscle damage, musculoskeletal flexibility, muscle strain injury and anterior cruciate ligament injury.

Dr. McHugh received his Ph.D. in exercise physiology in 1999 from the University of Wales, Bangor. Since 1999, Dr. McHugh has been the director of research at the Nicholas Institute of Sports Medicine and Athletic Trauma (NISMAT) at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City. He leads a multidisciplinary research team including orthopaedic surgeons, physical therapists, exercise physiologists, nutritionists, biomechanists, biomedical engineers and athletic trainers. The research encompasses areas such as randomized clinical trials in orthopaedic sports medicine, injury epidemiology, and basic and applied research in nutrition, physiology, and biomechanics. Dr. McHugh is a fellow of the American College of Sports Medicine and a member of the Orthopadeic Research Society. He is an adjunct professor in the department of physical therapy at New York University and has also held teaching positions in the department of physical therapy at Stony Brook University and the department of physical education at Hunter College in New York City. He has been a consultant with the New York Rangers hockey team since 2000. Dr. McHugh’s varied research interests include exercise-induced muscle damage, musculoskeletal flexibility, muscle strain injury and anterior cruciate ligament injury.

Passwater: Dr. McHugh, why did you become interested in exercise physiology? Mchugh: I was heavily involved in competitive sports from an early age and developed a keen interest in training techniques and optimal performance. Exercise physiology became a natural progression of that interest. Passwater: How did this interest lead you to directing and conducting research in sports medicine at the Nicholas Institute of Sports Medicine and Athletic Trauma at Lenox Hospital in New York City?

McHugh: I came to New York in 1987 to do a master’s degree in physical education and sport at New York University and, as part of that degree, did an internship at NISMAT. At the end of my internship, they offered me a position here and the rest is history.

Passwater: What does this Institute do in the way of sports medicine?

Passwater: What does this Institute do in the way of sports medicine?

McHugh: NISMAT was founded in 1973 by Dr. James Nicholas, the famed orthopaedic surgeon, and was the first hospital-based sports medicine institute in the country. Dr. Nicholas emphasized that sports medicine is about all aspects of athletic and recreational performance. NISMAT’s clinical research and education programs reflect this diverse approach to sports medicine.

Passwater: As an exercise physiologist, you are involved with both sports medicine and sports nutrition. Why do you like sports nutrition?

McHugh: Actually, I believe sports nutrition falls under the umbrella of sports medicine. I would not regard myself as an expert on sports nutrition, but my research in exercise-induced muscle damage and aspects of exercise recovery as well as recovery from injury have inevitably involved some aspects of nutrition. Luckily, we have an excellent nutritionist on staff, Beth Glace, who heads up most of our sports nutrition research.

Passwater: You are also a consultant to the New York Rangers. That sounds like fun. Not all professional teams understand the role of nutrition in performance.

Mchugh: My role there is primarily as an exercise physiologist involved with fitness testing and as a resource for assessing potentially beneficial products that might help their athletes with training and recovery. Nutrition is part of this, but most teams will have a dedicated sports nutritionist. I see my role as one of an objective assessor of the evidence for something actually working. As a researcher, I am naturally skeptical and with regard to sports nutrition, there are so many products out there with outlandish claims that athletes need some type of watchdog to bring them back to reality.

Passwater: Not all athletes realize that nutrition can have a very important role—directly and indirectly—in reducing injuries. Many injuries are caused by nutrition-related problems such as diminished mental and physical responses due to dehydration and low blood sugar. Injury is also caused by exercise- induced muscle damage. Before we chat about how nutrition helps reduce injuries, let’s start with a few basics.

What are some of the biochemical changes brought about by strenuous physical activity and why is it important to properly nourish the body before strenuous physical activity?

McHugh: The biochemical changes brought about by strenuous physical activity and the role of nutrition is a topic that has been extensively researched and would be hard to do justice to in a brief answer. My interest is in aspects of exercise recovery that we do not have a good handle on. For example, the nutritional strategies for optimal glycogen repletion and protein resynthesis are well understood and well-informed athletes and sports teams can easily introduce the appropriate strategies for nutritional needs pre-exercise, during exercise and post-exercise.

However, we know much less about how exercise stress affects the immune system. As prominent sports nutritionist Louise Burke recently stated in a British Journal of Sports Medicine article, “specific nutritional strategies to promote or preserve optimal antioxidant and immune function in athletes are not well understood”(1). We have terms like “burnout,” “overtraining” and “staleness,” which are hard to define and difficult to recognize before it is too late, and difficult to treat.

Sports with high levels of physical contact, multiple games in short periods of time, long seasons and constant travel, especially across time zones, place excessive stresses on athletes that cause an accumulation of what I like to refer to as subclinical musculoskeletal trauma. Recognizing subclinical musculoskeletal trauma before the athlete breaks down is critical. A recent study in the American Journal of Sports Medicine highlights the problem. Dupont and colleagues found that professional soccer players were six times more likely to get injured when they played two games a week compared with one game a week (2). Importantly, physical performance was not different when playing two games a week versus one game a week. So while athletes had recovered sufficiently to meet the energy expenditure required for the game, they were at a massively increased risk of musculoskeletal injury. I would attribute this to subclinical musculoskeletal trauma.

Passwater: Can we identify subclinical musculoskeletal trauma before it’s too late, and if so, what role does nutrition play in avoiding or treating this problem?

McHugh: When trying to identify and quantify subclinical musculoskeletal trauma, I think of the terrible triad of exercise recovery, which is the combination of muscle damage, inflammation and oxidative stress. Measuring appropriate markers of these factors over the course of a season or in response to particular events or periods of training is beneficial in identifying the problem. Physical interventions such as cryotherapy and massage, pharmaceutical interventions such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) and nutritional interventions such as antioxidant supplementation have been studied extensively with regard to preventing or treating muscle damage, inflammation and oxidative stress. Unfortunately, most studies have shown limited efficacy and interventions that provide comprehensive protection (i.e., show efficacy in limiting muscle damage, inflammation and oxidative stress) are needed.

Passwater: Strenuous physical activity can build muscle strength, but it can also tear down muscles. Bodybuilders have learned to optimize muscle building and they soon learn that “overdoing” does more harm than good. However, the competitive athlete must maximize effort throughout the competition. The result is usually inflammation that leads to soreness and injury. What processes are going on and why does inflammation result?

McHugh: The problem for many athletes is that their season is often dictated to them and can involve inadequate recovery time such as that which occurs with two soccer games a week. Sports such as professional tennis and golf have no defined off season and players inevitably break down. The inflammatory response to acute injury is well-understood and treatment regimens are well-defined. However, systemic markers of inflammation that fluctuate in response to exercise stress in the absence of an obvious injury are not as well-understood. Inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP) have been the focus of a lot of recent research with respect to exercise stress. Overtraining (now referred to as underperformance syndrome) has been linked to elevations in IL-6 and interventions that limit IL-6 elevations are thought to be important to achieving adequate recovery. This systemic inflammatory response to an exercise stress is a normal immune system response to a stressor and the body’s ability to appropriately adapt to the stress is part of the training adaptation.

However, when the stress is excessive or there is cumulative stress with inadequate recovery time, the immune system can be compromised and maladaptive training responses occur. For example, Nemet and colleagues showed that elevations in inflammatory cytokines following a period of intense training in adolescent wrestlers were associated with depression of anabolic growth factors (3).

Passwater: Muscle soreness is more than an inconvenience that requires rest. Doesn’t soreness mean that the athlete has destroyed some muscle tissue and then more is lost during the recovery period of rest?

McHugh: Muscle soreness is a normal response to unfamiliar exercise involving a predominance of eccentric contractions (eccentric contractions are commonly referred to as negative contractions and involve lengthening of the muscles during muscle contraction as occurs when one is lowering an object). However, our bodies adapt quite rapidly to protect us from repeated insults when we repeat the eccentric exercise. This is what happens when we begin a training program and are sore initially but then have minimal soreness as we adapt to the training. However, an increase in soreness in previously adapted athletes is a sign of an excessive stress. This could simply be a new addition to a training regime (e.g., downhill work), an increase in exercise volume that is not well tolerated or, more critically, an inability to tolerate continued training with no obvious change in volume or intensity. In this latter case, the cumulative exercise stress has reached a point where rest period may be inadequate. This type of response would be typical near the end of a long season or late in a tournament.

Passwater: Muscle soreness seems to be common sooner—such as mid-season— in younger athletes earlier in their careers. It seems to be common in minor league baseball pitchers. How can athletes minimize inflammation and soreness? Do foods and supplements such as fish oils and cherries help?

McHugh: I think people will be surprised and disappointed by what doesn’t work. The bottom line is that most nutritional interventions do not work for limiting exercise-induced inflammation or muscle damage. Better efficacy is seen with nutritional interventions for limiting exercise-induced oxidative stress. This makes sense given that most of the studies involved antioxidant supplementation which, by definition, would act on oxidative stress if the body’s natural antioxidant defenses are insufficient. Before everyone pushes aside their health foods and heads for the medicine cabinet, it is important to point out that NSAIDs also have a minimal effect on exercise-induced inflammation and muscle damage. In fact, NSAIDs have a detrimental effect on recovering muscles. Additionally, there is little evidence to support the use of other physical interventions such as cryotherapy or massage.

So does anything work? I have been very impressed by the findings in a series of studies that I have been involved with recently looking at the efficacy of a tart cherry juice drink (CherryPharm, Geneva, NY) for preventing exercise-induced muscle damage, inflammation and oxidative stress. In the first study, we just looked at makers of muscle damage following exercise of a single muscle group (4). Taking the juice for a few days prior to the exercise and on the days after the exercise prevented strength loss and reduced the pain response when compared to placebo.

The second study examined blood markers of muscle damage, inflammation and oxidative stress in exercising horses (horses are very susceptible to muscle damage) (5). Markers of muscle damage were reduced versus placebo by feeding the horses cherry juice for a week before the exercise, though there was no effect on inflammation and oxidative stress. We felt that this experimental model may have been inadequate to examine the effect of the juice on inflammation and oxidative stress (small sample and variable responses), so we decided to study marathon runners. In the third study, runners were given cherry juice or a placebo for four days prior to a marathon, on the day of the race and for two days after the race (6). The runners on the cherry juice showed a faster recovery of muscle strength, showed no signs of oxidative stress and had a markedly blunted inflammatory response when compared to placebo. The inflammatory markers IL-6 and CRP were 49% and 34% lower with cherry juice versus placebo.

Passwater: How should an athlete use cherry juice? Pre-game? Post-game? All day long?

McHugh: The correct answer is that we do not know the optimal dose or timing. However, it is not advisable to drink fruit juices immediately prior to or during exercise as this can lead to gastrointestinal distress. Commercially available carbohydrate and electrolyte drinks or plain water for short-duration exercise are more appropriate to meet hydration needs immediately prior to and during exercise. With respect to cherry juice, all human trials to date using this CherryPharm juice have used a dosage of two bottles per day (originally the bottles were 12 oz., but now they are 8 oz. for the same number of cherries—approximately 45 per bottle). Study subjects have been advised to take one in the morning and one in the afternoon or evening. It may be beneficial to cycle on and off the juice to correspond with periods of intense training or competition. The key is to make sure the regimen begins several days prior to the exercise stress. The idea is “precovery” as opposed to recovery.

Passwater: Precovery—interesting word and concept. Cherries have a long history of reducing pain and inflammation such as experienced with arthritis and gout. Are the same nutrients involved in reducing muscle soreness?

McHugh: Actually, I am involved in an ongoing clinical trial examining the efficacy of tart cherry juice for alleviating the symptoms of osteoarthritis. Yes, we think the same nutrients are involved.

Understanding why the juice used in these studies showed efficacy can help us understand how foods in general can have medicinal effects and what factors are critical to the efficacy of nutritional interventions. There are three basic questions to be answered before incorporating a nutritional intervention for potential medicinal effects. The first question is whether the particular food contains phytonutrients known to have medicinal effects? With respect to cherries, and tart cherries in particular, numerous different phytonutrients have been identified in cherries that have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory actions (e.g., quercetin, ellagic acid, melatonin, cyanidin).

The second question is how much of a particular food or food extract needs to be consumed to reach medicinal effects? With respect to cherries, research has shown that eating approximately 50 cherries a day can reduce systemic inflammatory markers in healthy subjects. However, it would be difficult to achieve compliance with a nutritional intervention that requires athletes to eat 50 cherries a day. Juices provide a more practical delivery mechanism and the health food industry is saturated with foods and drinks that are condensed versions of a natural food. The 8-oz. cherry juice bottles used in our research contained approximately 45 cherries and the dosage was two bottles per day taken on two different occasions (12 for horses based on body mass difference).

The third question is to what extent do harsh food processing techniques degrade the phytonutrients in the particular food or drink? In this regard, a not-from-concentrate juice will be better than a fromconcentrate juice. But even with not-from-concentrate juices, the process of taking a fruit from its natural state to a bottled product will degrade the active ingredients. Furthermore, juices are further degraded by heat and direct sunlight, and shelf life is an important issue. In this regard, the antioxidant capacity for the CherryPharm juice used in our studies was 70–500% higher than values reported for other commercially available juices such as grape juice, black cherry juice, pomegranate juice, blueberry juice, acai juice and cranberry juice. This suggests that the active ingredients were well maintained.

Interestingly, the muscle damage model of our first study has been replicated in studies using pomegranate extract, cherry extract and pomegranate juice. While there was some evidence of protection against strength loss, the magnitude was markedly less than that seen in our study. My take is that the closer you stay to the natural food, the better will be your efficacy. Eating 90 tart cherries a day might be optimal, but may not be enjoyable.

Passwater: Do any professional teams follow this advice?

M

cHugh: I am not at liberty to comment on what certain teams use in terms of nutritional or other interventions to facilitate exercise recovery. However, in the last four years, teams that have been using a regimen of the tart cherry juice that we have studied have won two NCAA football championships, an NCAA men’s basketball championship and a Stanley Cup in ice hockey.

Passwater: Timing of foods and nutrients is important. In general, as an exercise physiologist, what do you suggest athletes do to maximize performance and, specifically, what should they do to reduce risk of injury and soreness?

McHugh: A sports nutritionist would be better qualified than I to answer this question. However, it is important to point out certain misconceptions about accepted nutritional practices. For example, it is well established that protein resynthesis can be improved by providing dietary protein after strenuous workouts (e.g., a glass of milk after strength training). The problem is that it is also commonly suggested that post-exercise protein consumption is important for preventing exercise-induced muscle damage. Unfortunately, the effects of protein supplementation on recovery from exercise-induced muscle damage are small. Interestingly, CherryPharm have produced a tart cherry juice drink with added protein. I am not aware of any research on this drink, but it is my post-exercise drink of choice. I think of it as killing two birds with one stone. Athletes are advised to take a bottle of cherry juice with protein within 30 minutes after a strenuous workout as part of the two bottles a day regimen.

Passwater: Thank you, Dr. McHugh, for informing us about the role of nutrition in sports performance, exercise-induced muscle damage and recovery. WF

References

1. L. Burke, “Fasting and Recovery from Exercise,”Br. J. Sports Med. 44 (7), 502–508 (2010).

2. G. Dupont et al., “Effect of 2 Soccer Matches in a Week on Physical Performance and Injury Rate,” Am. J. Sports Med. Apr 16, 2010. Epub ahead of print.

3. D. Nemet, et al., “Cytokines and Growth Factors During and After a Wrestling Season in Adolescent Boys,” Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 36, 794–800 (2004).

4. D.A. Connolly, et al., “Efficacy of a Tart Cherry Juice Blend in Preventing the Symptoms of Muscle Damage,” Br. J. Sports Med. 40 (8), 679–683 (2010).

5. N.G. Ducharme, et al., “Effect of a Tart Cherry Juice Blend on Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage in Horses,” Am. J. Vet. Res. 70 (6), 758–763 (2009).

6. G. Howatson, “Influence of Tart Cherry Juice on Indices of Recovery Following Marathon Running,” Scand J. Med. Sci. SportsOct 21, 2009. Epub ahead of print.

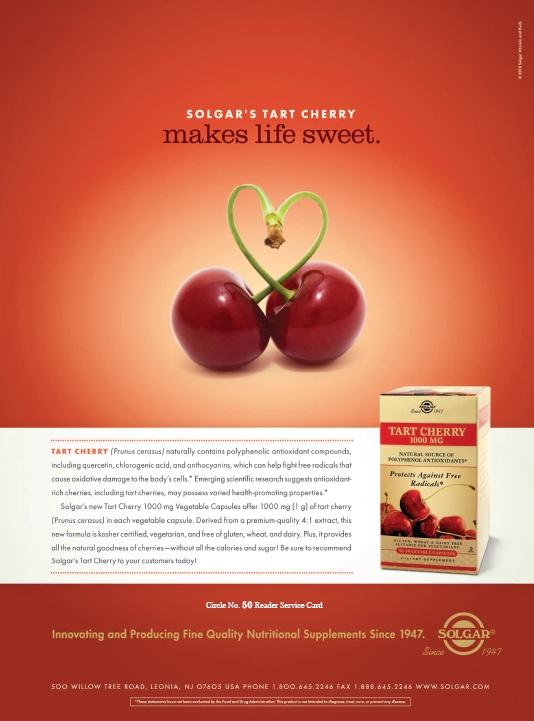

Dr. Richard Passwater is the author of more than 40 books and 500 articles on nutrition. He is the vice president of research and development for Solgar Vitamin and Herb. Dr. Passwater has been WholeFoods Magazine’s science editor and author of this column since 1984. More information is available on his Web site, www.drpasswater.com.

Published in WholeFoods Magazine, October 2010